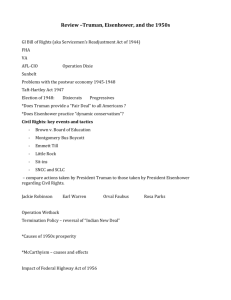

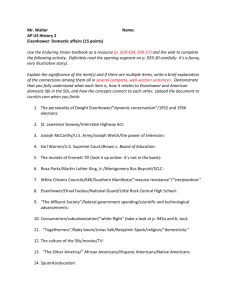

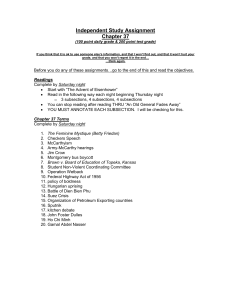

27 America at Midcentury, 1952–1960 “I

advertisement