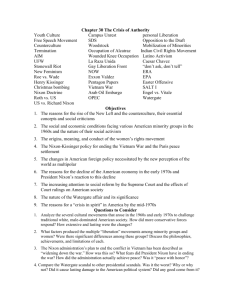

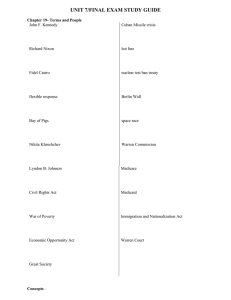

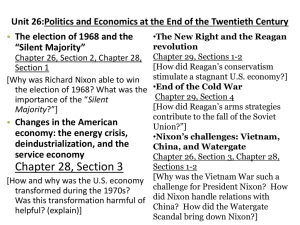

29 A Time of Upheaval, 1968–1974 D

advertisement