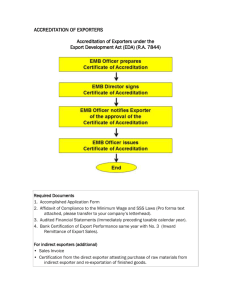

Step-by-Step Gu de to Export ng

advertisement