Table of Contents ____________________________________________________________________________________

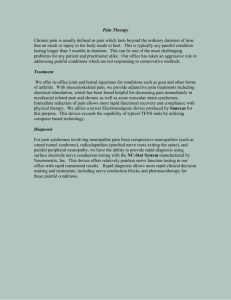

advertisement