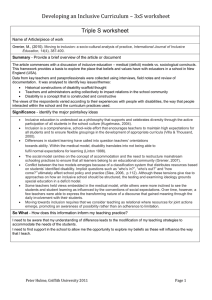

INDEX FOR DEVELOPING INCLUSIVE SCHOOLS

advertisement