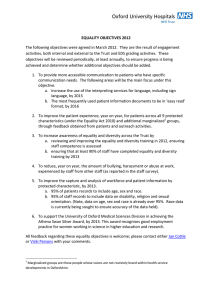

NCERT

advertisement