2.5 EXAMINATION REFORMS

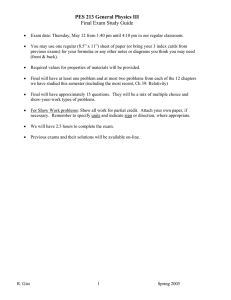

advertisement