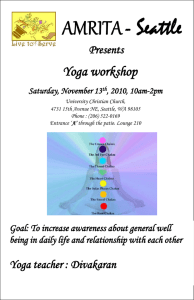

3.5 H P

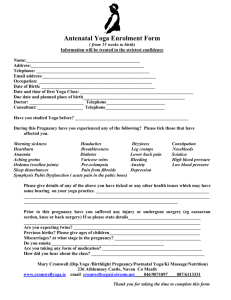

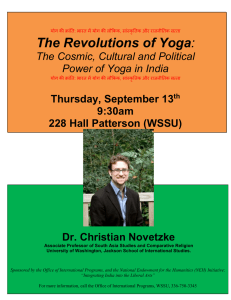

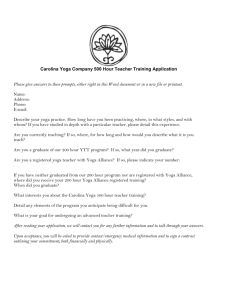

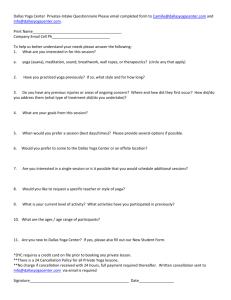

advertisement