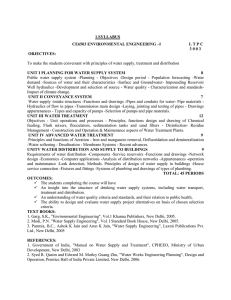

2.2 S R

advertisement