The State of State Science Standards: 2005

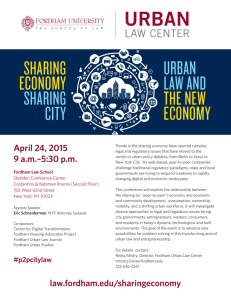

advertisement

The Charles A. Dana Center’s Response to the Thomas B. Fordham Institute’s The State of State Science Standards: 2005 In December 2005, the Fordham Institute, a Washington, D.C.–based think tank, released its State of State Science Standards and gave a failing grade to the Texas science standards—the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS). While the Institute’s attempt to identify high-quality science curricula is laudable, its assessment of the Texas standards is compromised by factual errors and marred by an ideological approach to teaching science that is outside the mainstream of expert scientific opinion. No one likes to be given a failing grade. But sometimes, the failure is in the grading, not in the work being graded. We address below a few of the recurrent themes of the Fordham report. On Teaching Students Science One of the challenges of good science education is balancing the need to help students learn the methods of systematic scientific inquiry with the need to help students master a large and growing body of scientific facts and principles. Even students who do not pursue science-based careers must learn to observe, analyze, and use scientific ways of thinking so that, as lifelong learners, they will be able to make informed decisions in an increasingly complex world. But effective application of scientific methods requires that students know a great deal about the world around them—and that includes many facts, figures, and, as they get older, specialized mathematical and scientific techniques. A balanced view of science education is supported by modern cognitive psychology and is reflected in the model standards developed by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and the National Research Council (NRC). The Texas science standards were developed by master science teachers and practicing scientists. Their efforts were influenced by current research on learning and by the work of these national science leadership organizations. In sharp contrast with the fundamental tenets that underlie the views of the NRC and the AAAS, the Fordham Institute reviewers express antipathy toward inquiry. They call efforts to engage students in building their own understanding “absurd and dysfunctional.” Thus, it is not surprising that balanced, inquiry-based standards such as the TEKS are rated much less favorably than a curriculum that primarily lists facts for students “to know” or memorize. On Respect For Our Students and Their Potential The Fordham reviewers devote considerable space and energy decrying what they see as political correctness in state science standards documents. They see efforts to honor and highlight the contributions of members of American ethnic groups to science as intellectually dishonest. They assert, for example, that “Examples of real and important scientific achievement in cultures different from our own, past and present—real science from the ancient Chinese and Arab cultures, for example—are welcome in science teaching. But: none of that means that every individual is, or can be, a scientist.” We do not agree. In Texas, we believe that highlighting the real contributions of presentday members of American ethnic groups to the advancement of science is appropriate, pedagogically useful, and an important reminder to our children that science is a human endeavor open to those work hard and seek knowledge. For too long and in too many places, science education has been shaped by the presumption that not every child can be a scientist. The view articulated by the Fordham reviewers has not served our nation well. On Sharing Practitioner Wisdom In an unfortunate error, now acknowledged on their website, the Fordham reviewers evaluated instructional resources developed by Texas science teachers for science teachers—“Snapshots: Ideas for classroom activities that address the intent of the TEKS for science”—as if they were a component of the state science standards. They are not. The reviewers took a few of the more whimsical suggestions among the hundreds assembled by Texas teachers and scientists and used them to attack the integrity of the standards. Motivating students and keeping them engaged in a rigorous science program is hard work. Unlike the Fordham reviewers, we see no problem in asking young elementary school students to dress up as atoms and describe their properties to their classmates as long as the teaching of science is well considered and the content is accurate. The Snapshots, along with other TEKS support materials, are available free of charge on our website. We encourage interested readers to review them for themselves at http://www.utdanacenter.org/sciencetoolkit. The Fordham Institute report can obtained from their headquarters, 1701 K Street, NW, Suite 1000, Washington, D.C., 20006, or at their website: http://www.edexcellence.net/institute. We have great respect for the Fordham Institute, and appreciate the often constructive role it plays in public understanding of American educational issues. In this case, however, it’s the Fordham reviewers who deserve an “F.” Philip Uri Treisman Executive Director Charles A. Dana Center The University of Texas at Austin