T S I C

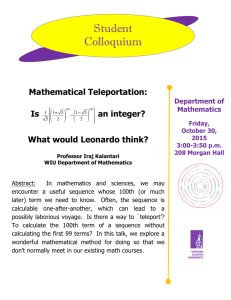

advertisement