The Maine Physical Activity and Nutrition Plan 2005-2010

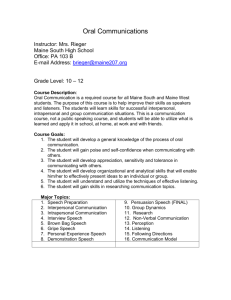

advertisement