Synthesis of Research on Disproportionality in Child Welfare: An Update

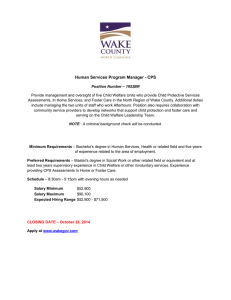

advertisement