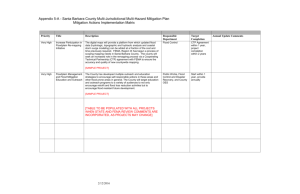

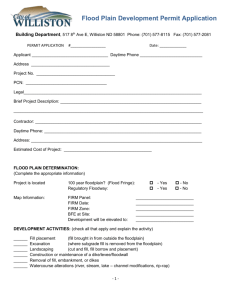

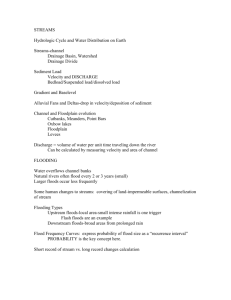

Managing Risk to Humans and to Floodplain Resources

advertisement