Big Brothers Big Sisters Ireland Youth Mentoring Programme Galway, Mayo & Roscommon

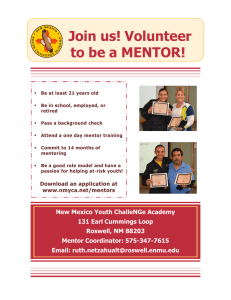

advertisement