Making decisions A guide for people who work in health OPG

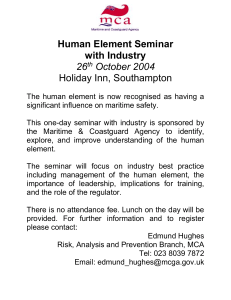

advertisement