OFFSHORE OIL AND GAS GOVERNANCE IN THE ARCTIC

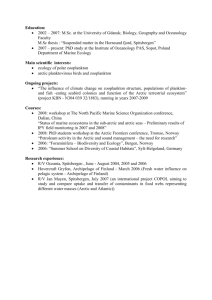

advertisement