Gender Differences in Psychosocial Factors influencing Care of CVD Holly Mead, PhD

advertisement

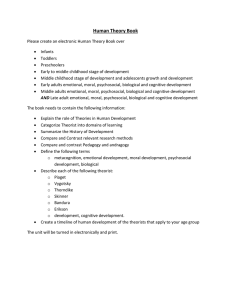

Gender Differences in Psychosocial Factors influencing Care of CVD Holly Mead, PhD Assistant Research Professor Department of Health Policy The George Washington University AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting Gender Interest Group June 26, 2009 Background g Psychosocial factors are significant risk factors f CVD morbidity, for bidi mortality li post event1 Exacerbate behavioral risk factors Hamper lifestyle changes Impede adherence to medical recommendations Poor self-management can lead to Secondary y events Additional interventions Re-hospitalization hospitalization Re 2 Background g Women more likely to experience psychosocial , problems following cardiac event2,3 Depression Insomnia Anxiety Women less likely to use available resources4 Despite evidence, psychosocial factors are not generally acknowledged as risk factors by MDs5 3 Objective j To examine psychosocial factors affecting adjustment dj to, management off CVD To explore gender differences in how PS factors affect CVD patients’ self-management Different factors affect illness, care Factors affect illness, care differently To inform development, implementation of effective interventions that address PS factors in CVD recovery 4 Methodology gy Qualitative study investigating patient selfmanagement among CVD patients i Convened 33 focus groups; 401 CVD patients Questions focused on challenges getting care, coping with illness, managing disease Conducted thematic content analysis to identify barriers to effective self-management Compared C d themes h by b gender d to examine i differences in experiences, perspectives 5 Participant p Characteristics Gender breakdown → 52% female; 48% male Women more likely to be minorities 82% minority O Over 50% with ith incomes i < $25K annually ll Women more likely to report low household incomes Insurance 1/3 Medicaid 13% privately insured 12% % Medicaid 12% uninsured 6 Findings Table 1. Domains and Themes Negative 1) Depression (n=58) emotional 2) Fear (n=21) states 3) Anger & hostility (n=9) Chronic life stressors 1) Disease stress (n=16) 2) Financial stress (n=16) Social factors 1) Social isolation (n=11) 2)) Burden u de to family a y & friends e ds ((n=12)) 3) Social Support (n=48) 7 Findings: g Psychosocial y Domains Chart 1: Gender Analysis by Psychosocial Domains 100 Percen ntage of Refe erences 90 80 70 60 Male 50 Female 40 30 20 10 0 N Negative ti emotional ti l state t t Ch i lif Chronic life stressors t Psychosocial Dom ains 8 S i l ffactors Social t Findings: Emotional States P ercen tagg e o f R eferen cces Chart 2: Negative Emotional States by Gender 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 M l Male Female depression fear Negative Emotional States 9 anger Findings: Emotional States Depression was the most commonly discussed PS factor interfering with self-management Men slightly more likely than women to raise as issue “What you used to love you can’t do. I used to love to go ffishing, g huntingg and swimming, g but I can’t do that now. You get to where you don’t care if you wake up the next morning.” – male participant “I suffer from depression, and the more depressed I am, the more…I can’t stop eating… I’m ashamed to say it, but I don’t don t know how to control myself myself.” – female participant 10 Findings: Emotional States Women were more likely W lik l to t express fear f related l t d to their disease; possibility of death “The day I went home, that night I was scared. I wouldn’t lie down to go to sleep. I was afraid to go to sleep I just didn sleep. didn’tt know. know There was the fear of the unknown.” – female participant 11 Findings: Emotional States Men were more likely to convey anger, anger frustration around loss of former life “You’ve You ve been working your whole life and they throw a heart attack up on you and you can’t work…. Now my wife f is working, g, paying p y g all the groceries, g , all the bills byy herself. Yes, this pisses me off.”– male participant 12 Findings: Life Stressors Percentage P e of Reference es Chart 3: Chronic Life Stressors by Gender 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Male Female Disease stress Financial Stress Chronic Life Stressors 13 Findings: Life Stressors Women were much more likely to discuss stress, worryy related to disease,, management g of care “I have high blood pressure and heart trouble, and sometimes, though you take your medication, you have a h d h [[and] headache d] you ddon’t ’ kknow if it’s i ’ possible ibl you might i h have a stroke or just a normal headache.” – female p participant p Men were more likely to discuss stress related to financial burdens, employment issues “The amount of bureaucratic red tape that people have to go through [is] stressful. You worry about how you’re going to pay for it and that only adds to it it.” – male participant 14 Findings: Social Factors Chart 4: Social Factors by Gender Percentag ge of Referenc ces 100 80 60 Male 40 Female 20 0 social isolation burden on family, friends Social Factors 15 social support Findings: g Social Support pp Women more likely y to feel sociallyy isolated; worry about being a burden to family, friends “I'm so afraid f off becomingg a recluse because I'm so weak and tired. I'm afraid to go out and do anything.” – female participant “You worry about being a burden on your family, but you don’t know what to do. So a lot off times…you y don’t talk to them because you don’t want them to know that it’s really that bad.” – female participant 16 Findings: g Social Support pp Men were more likely y to talk of the critical role their spouses play in their care “Myy wife f does all this stuff ff like a nurse. That’s her first f priority. I say ‘why I gotta take 11 pills this morning’ and she says I wanna see you alive.”– male participant Both men, women participating in cardiac great benefit of program p g rehabilitation discussed g “This group is very important… Prior to being in the p g program we didn’t keepp our diets or our appointments pp and now we do it together.” – female participant 17 Conclusions Both genders experience extensive psychosocial issues Affect ability to adjust to, cope with CVD Impede management of CVD qualityy of life Alter q 18 Conclusions Women, men experience psychosocial factors in unique gender-specific unique, gender specific ways For women More in in-line line with social role as caregivers6 Reflects women’s feelings of vulnerability to illness7, 8 For men More in-line with social roles as providers, head of family9,10 Reflects undermining of notions of masculinity 19 Implications for Practice Acknowledge g psychosocial py factors as legitimate g risk factors Routinely screen for range of psychosocial issues Develop interventions targeted to unique experiences of women, women men Promote use of available resources 20 Implications for Policy Support HEART Act and other legislation to st d diseases from uniquely study niq el female perspective perspecti e Reform finance and delivery models Shift to holistic model of care that encompasses biopsychosocial health model11 Ensure adequate reimbursement for psychosocial screenings, interventions 21 Acknowledgments Coauthors: Ellie Andres, Christal Ramos, Bruce Siegel, Siegel Marsha Regenstein. Regenstein This research was generously funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundations’ Expecting Success: Excellence in Cardiac Care program Contact information: khmead@gwu.edu 22 References 1 1. 2. 3. 4. 5 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11 11. Sowden, G Sowden G. L L., & Huffman Huffman, JJ. C C. (2008) (2008). The impact of mental illness on cardiac outcomes: A review for the cardiologist. International Journal of Cardiology, 132, 30-37. Brezinka, V., & Kittel, F. (1995). Pschosocial factors of coronary heart disease in women: a review. Social Science & Medicine, 42, 1351-1365. Pycha, C., Gulledge, A.D., Hutzler, J., et al. (1986). Psychological responses to the implantable defibrillator: Preliminary observations. Psychosomatics, 27, 841–845. van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Sanderman, R., Ranchor, A. V., Ormel, J., van Veldhuisen, D. J., & Kempen, G. I. J. M. (2002). Gender-specific changes in quality of life following cardiovascular disease: A prospective study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 55, 1105-1112 [1] Feinstein, Feinstein R. R E., E Blumenfield, Blumenfield M., M Orlowski, Orlowski B., B Frishman, Frishman W. W H., H & Ovanessian, Ovanessian S. S (2006). (2006) A National Survey of Cardiovascular Physicians' Beliefs and Clinical Care Practices When Diagnosing and Treating Depression in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. Cardiology in Review, 14, 164-169. McBride, A. B., & McBride, W. L. “Women’s Health Scholarship: From Critique to Assertion.” Reframing Women's Health: Multidisciplinary Research and Practice. Ed. Alice J. Dan. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994. “Work, Motherhood, Physician Counseling & Caregiving Are Among Key Influences On Women's Health: Analysis Of Landmark Women's Health Survey Reveals Complex Interaction Of Health, Health System, And Social Factors.” The Commonwealth Fund, 2001. Auerbach, Judith and Anne Figert. “Women’s Health Research: Public Policy and Sociology.” Journal of Health ea t and a d Social Soc a Behavior, e av o , 36, Extra t a Issue ssue (1995): ( 995): 115-130. 5 30. O’Brien, R., Hunt, K., & Hart, G. (2005). “It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate’: men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking.” Social Science & Medicine, 61, 503-516. Con, A. H., Linden, W., Thompson, J. M., & Ignaszewski, A. (1999). The psychology of men and women recovering from coronary artery bypass surgery.” Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation, 19, 152-161. D A Dan, A. K K. JJonikas, ik JJ. A A., & F Ford, d Z Z. L L. “E “Epilogue: il A An IInvitation.” it ti ” Reframing R f i Women's W ' Health: H lth Multidisciplinary Research and Practice. Ed. Alice J. Dan. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994. 23