Health Services and Pharmacoepidemiological

advertisement

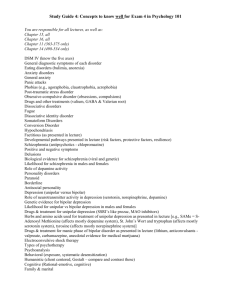

Health Services and Pharmacoepidemiological Research with CMS Datasets Stephen Crystal y Center for Education and Research on Mental Health Therapeutics Rutgers University Presentation for CMS Databases Session Annual Meeting of AcademyHealth June 29, 2009 1 Organization of Talk • Potentials, limitations, strategies for HSR and d CER with ith CMS d datasets. t t F For d details, t il see handout (Medical Care paper). • Wh Whatt is i MAX ((super-briefly). b i fl ) F For d details, t il see handout (CMS MAX slides). • Ill Illustrative t ti applications li ti ffrom work k att our center focusing on mental health treatments – supported t d by b AHRQ CERT CERTs award d ffor the th Center for Education and Research on Mental Health Therapeutics; NIMH; FDA; Retirement Research Foundation. 2 Unique Potentials of CMS Datasets for HSR, Pharmacoepi and Comparative Effectiveness Research • Ability to examine care for very large large, “real-world” real world patient populations. Includes expenditures (but second payer for duals). Window into care for many of the most vulnerable. • Inclusion of subgroups typically underrepresented in primary-data-collection studies. • Statistical power to study many subgroups of interest and l low-frequency f characteristics h t i ti and d events. t • Utilization information that does not rely on self-report. • Ability to update results over time cost cost-effectively. effectively • Diagnostic information provided directly by providers. • Ability to follow longitudinal patterns of care across multiple settings, including duration and consistence of prescribed medication use. 3 Methodological Challenges and Strategies to Address Them (Ongoing Good News/Bad News Joke) • Limited clinical detail (can be addressed with strategies such as data linkage). • Identification of clinical subgroups of interest may not be straightforward. – Need for more validation studies of case identification algorithms using diagnostic codes in claims data data. • Lurie et al: 1 inpt/2 outpt algorithm highly specific for schizophrenia. • Walkup, Crystal et al: validated claims-based measure of HIV/AIDS vs. a state registry. – More such validation studies needed to support CER CER. – Linkage to registries can be powerful tool (eg SEER). 4 Who Are We Looking At? How Do We Examine Treatment Use Over Time? • MAX includes full utilization/diagnostic histories for FFS only. Important to understand who is in FFS population in each state (healthy kids? mostly disabled kids?). • Measures of medication consistency/persistence. – Prescription drug claims provide the ability to examine longitudinal patterns of medication use during usual care among gp persons with chronic illnesses in diverse settings. g Multiple measures: eg time-to-gap, proportion of observation time covered by scripts. – Most appropriate measures will vary depending on circumstances. For example, for antiretrovirals, effective therapy entails indefinite and highly consistent use. In p HEDIS measures p provide a contrast, for antidepressants, benchmark for adequate duration of a treatment episode. 5 Other Challenges • Dispensed does not necessarily mean taken. Requiring at least one refill increases likelihood that medication is used, but creates potentials for bias related to initial response. Many challenges in choice h i off d designs i ((e.g. “i “intention-to-treat”/first t ti t t t”/fi t exposure carried i d forward versus as-treated) depending on specific study questions and circumstances. • Challenge Ch ll off confounding f di b by iindication di ti ((unobserved b d clinical li i l ffactors t associated with prescribing decisions). • Limited range of outcomes to assess. Outcomes often non-specific ( (e.g., “cardiac”, “ di ” ttotal t l mortality) t lit ) and d causes off d deaths th unclear. l • Financial considerations may bias clinical information on claims (e.g., diagnoses). – for more gory detail, see Crystal et al, “Studying Prescription Drug Use and Outcomes with Medicaid Claims Data: Strengths, Limitations, and Strategies.” Medical Care 2007 (paper from previous AHRQ methods conference). 6 Utility for Comparative Effectiveness Research • CER often requires very large study populations with power to examine adverse events not detectable with typical RCT sample sizes; examine outcomes in particular subgroups of concern; compare outcomes across individual drugs within and between classes;; assess risks of adverse outcomes not detectable in typical clinical trials. • Very large numbers also needed to examine treatment effect h t heterogeneity it and d effect ff t modifiers; difi construct t t carefullyf ll tailored new-treatment cohorts; and utilize advanced statistical methods such as high dimensionality propensity scoring and instrumental variables. These designs are remarkably demanding of power and may require multi-year q y address some important p national data to adequately questions, as in our current study on CE of antipsychotics. 7 C ’t W Can’t We Just J tR Rely l on RCT RCTs? ? The “Gold Standard” But... • Trials not always feasible/ethical. Much use is offlabel and for indications/conditions on which evidence is scarce or absent. • Efficacyy in selected p populations p vs. effectiveness in usual care. Treated populations often highly clinically heterogeneous while RCTs typically aim to reduce d h heterogeneity t it with ith iinclusion/exclusion l i / l i criteria. Result: available evidence often lacks external validity validity. 8 Typical RCTRCT-Based Evidence vs. vs Usual Care RCTs Usual Care Duration Typically Short-Term Often Long-Term Comparators Typically PlaceboControlled; Head-toHead Trials Scarce Pressing Need for Data on Comparative Outcomes to Inform Clinical Decisions Complex Comorbidity is Common in Treated Population Population Patients with Complex Comorbidities Often Excluded 9 What is MAX? • Person Person--based Medicaid data used for – Research/evaluation – Epidemiology/quality – Statistics/forecasting • Calendar Year (begins 1999, SMRF - prior years) • Event Based – Occurrence of eligibility – Dates of service – Final action events (hospital stays, visits, etc.) • Derived from MSIS (7 calendar quarters) 10 Why Do We Need MAX? • Eligibility – Retroactive R t ti eligibility li ibilit iin proper chronology h l – Eligibility codes – verified and improved – Eligibility data added to each claim • Services (Claims) – Final action events (interim claims combined) – Organized by dates of service – Type of service – verified and regrouped • Person Summary File – Calendar year eligibility and summary of claims – Not available from f MSIS SS 11 MAX Data Sets • Person Summary File – Eligibility (annual and monthly) – Managed care enrollment – Utilization and Medicaid payment by type of service • Service Files – Inpatient I ti t hospital h it l – Long term care – Prescription drug – Other Oth Services S i • Service file records include – Fee Fee--for for--service – Prepaid plans - premium payments and encounters (incomplete) • See handout as well as RESDAC and CMS websites for more details on MAX datasets. 12 Illustrative Applications: Selected Studies From Our Group Using MAX • Off-Label Use of Atypical Antipsychotics in Youth and Elderly (Crystal et al al, in press press, Health Affairs) Affairs). • Antidepressant Use and Suicidality Among Medicaid Youth ((Olfson et al, Archives of General Psychiatry, y y 2006). ) • Mood Disorder Hospitalization Among Medicaid Benes (Prince, Crystal, AJPH 2009) • Comparative Effectiveness of Antipsychotics in Early Onset Schizophrenia (current). • G Guideline id li C Consistency, i t C Comparative ti S Safety f t and d Effectiveness of Antipsychotics in Nursing Home Elderly (current). – support from AHRQ CERTs award, FDA, NIMH, Retirement Research Foundation. 13 Off--Label Use of AAPs in Youth and Off Eld l --Overview Elderly-Elderly O Overview i • Increased use of atypical antipsychotic (AP) medications for a broadened range of patients and indications, often off-label, has raised a range of policy challenges for payers, patients and clinicians. US is outlier in off-label use patterns, esp. in youth. • Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries utilize a large share of AAPs and these data are critical for understanding use and outcomes. • Particular concerns about increased use among youth and among elderly with dementia. 14 Earlier Antipsychotics: P Powerful f l Meds, M d Limited Li it d Use U • Beginning in the 1950s with introduction of chlorpromazine, AP drugs have transformed care for the seriouslyy mentallyy ill. • Until the 1990s, however, use of APs was largely ese ed for o adu adults s with sc schizophrenia op e a a and do other e reserved severe psychotic disorders, treated by psychiatrists. Treatment was understood to involve balancing b beneficial fi i l iimpactt on hi highly hl di disabling bli symptoms t with ith significant risks. 15 The Advent of the AAPs • Approval of risperidone (1993), olanzapine (1996), quetiapine (1997), ziprasidone (2001), aripiprazole (2002) was ffollowed ll db by iincreased d and db broadened d d use. AAPs perceived as much safer and more your father’s antipsychotic.” p y efficacious – “this is not y • Medication costs previously a relatively small part of mental health budgets, but AAPs were much higherpriced, and more-aggressively marketed (including DTC in recent years). For Medicaid, AAPs became the most costly class of drugs. Total US sales: $13.1 billion by 2007. • Use increasingly g y expanded from psychiatrists y to primary care. Some broadening of indications but much of expanded use was off-label. 16 National Medicaid Expenditures on A ti Antipsychotic h ti Agents A t Highest Cost Drug Groups (in Millions $) Among Nondual Eligible Beneficiaries Rank 1 1999 Antipsychotics ($700)) ($ 2001 Antipsychotics ($1,174) ($ , ) 2003 Antipsychotics ($1,898) ($ , ) 2 Antidepressants ($513) Antidepressants ($807) Antidepressants ($1,085) 3 Antivirals ($452) Anticonvulsants ($619) Antivirals ($950) 4 Anticonvulsants ($388) Antivirals ($612) Anticonvulsants ($966) 5 Ulcer Drugs ($328) Ulcer Drugs ($574) Antiasthmatics ($986) Esposito, D et al., Trends in Medicaid Prescription Drug Use and Costs: 1999 to 2002. Evidence from Medicaid Analytic eXtract Data. Presented at Academy Health 2007; and CMS, Chartbook: Medicaid Pharmaceutical Benefit Use and Reimbursement in 2003, http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/downloads/Pharmacy_RX_Chartbook_2003.pdf 17 Use Among Children and Youth • 5 5-fold f ld iincrease iin AP use 1993 1993-2002; 2002 challenging h ll i b behavior h i such as aggression thought to motivate much current use. • FDA-approved indications in youth limited to schizophrenia, autism, ti T Tourette’s tt ’ and d bipolar bi l mania. i • Concerns about off-label use include increasing evidence on adverse metabolic side effects as well as worries about longt term developmental d l t l effects. ff t • Medicaid programs among concerned stakeholders. • How much of use is off-label off label and what diagnoses account for use? How much due to increased diagnosing of bipolar? • Utilization analyses presented to Medicaid Medical Directors, NASMD, CMS and other concerned parties. MAX analyses served as “template” for analyses of more-recent data by ~15 collaborating states in Medicaid Medical Directors Learning Network. MAX also useful to compare to privately insured. • Utilization and policy challenges with AAPs -- in press, Health Affairs). 18 Increasing Use of Antipsychotics Among Youth 6-17 Percent w P with AP Us se Medicaid ((7 States*)) Privatelyy Insured 4.5 4 35 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 05 0.5 0 * CA, FL, GA, IL, NY, OH, TX 19 AP Use by Hierarchical Diagnostic Group in Medicaid Youth Ages g 6-17* 2001 N=51,093 2004 N=88,096 4 0% 4.0% 3 3% 3.3% Group 2 - Autism 5.3 4.9 Group p 3 - Bipolar p Disorder 14.2 18.7 Group 4 - Conduct Disorder or DBD w/o ADHD 10.9 8.9 Group 5 - Conduct Disorder or DBD w/ ADHD 10.4 9.0 Group 6 - ADHD 27.5 29.1 Group 7 - Anxiety or Depression 9.5 9.1 Group 8 - Substance Abuse 04 0.4 06 0.6 Group 9 - Adjustment Related Disorders 2.0 1.5 Group 10 - Other MH Disorders 6.3 5.9 Group 11 - None of Above 9.6 9.1 G Group 1 - Schizophrenia S hi h i * 7 State Medicaid Data (CA, FL, GA, IL, NY, OH, TX). 20 Diagnosis Rates in Medicaid Youth Ages 6-17* 2001 N=1,841,048 2004 N=2,101,866 0.15% 0.19% G Group 2 - Autism A ti 0 40 0.40 0 50 0.50 Group 3 - Bipolar Disorder 0.63 1.11 2 13 2.13 1 98 1.98 0.98 1.00 Group 6 - ADHD 6.09 7.28 Group 7 - Anxiety or Depression 2.51 2.89 Group 8 - Substance Abuse 0.40 0.52 Group 9 - Adjustment Related Disorders 1.77 1.61 Group 10 - Other MH Disorders 4.70 4.42 Group 11 - None of Above 80.24 78.51 Group 1 - Schizophrenia Group 4 - Conduct Disorder or DBD w/o ADHD Group 5 - Conduct Disorder or DBD w/ ADHD * 7 State Medicaid Data (CA, FL, GA, IL, NY, OH, TX) 21 AP Treatment Rates within Diagnostic Groups in Medicaid Youth Ages 6-17* 6-17 2001 N=51,093 2004 N=88,096 75.6% 75.1% Group 2 - Autism 36.4 41.3 Group 3 - Bipolar G Bi l Disorder Di d Group 4 - Conduct Disorder or DBD w/o ADHD Group 5 - Conduct Disorder or DBD w/ ADHD Group 6 - ADHD 62 4 62.4 70 8 70.8 14.2 18.7 29.4 37.7 12.5 16.8 Group 7 - Anxiety or Depression 10 5 10.5 13 2 13.2 Group 8 - Substance Abuse 2.7 4.6 Group 9 - Adjustment Related Disorders 3.1 3.8 Group 10 - Other MH Disorders 3.7 5.6 Group 11 - None of Above 0.3 0.5 Group 1 - Schizophrenia * 7 State Medicaid Data (CA, FL, GA, IL, NY, OH, TX) 22 AP Use by Hierarchical Diagnostic Group in Privately Insured Youth Ages 6-17* 6-17 Group 1 - Schizophrenia Group 2 - Autism Group 3 - Bipolar Disorder Group 4 - Conduct Disorder or DBD w/o ADHD 1996 N=349 2001 N=4,061 2004 N=16,192 2006 N=17,523 8.0% 3.6% 2.5% 2.2% 3.4 4.4 4.4 5.2 11 5 11.5 23 8 23.8 22 9 22.9 25 2 25.2 6.6 6.3 4.5 4.5 Group 5 - Conduct Disorder or DBD w/ ADHD Group 6 - ADHD 3.7 4.1 2.8 2.9 17.8 18.5 18.9 21.4 Group 7 - Anxiety or Depression 19.5 18.0 16.7 16.0 Group 8 - Substance Abuse 0.3 0.4 0.6 0.5 Group 9 - Adjustment Related Disorders 2.0 1.4 1.2 1.5 Group 10 - Other MH Disorders 4.6 6.4 5.7 6.0 Group 11 - None of Above 22.6 13.1 19.8 14.6 * MarketScan Research Databases 23 U A Use Among Child Children and d Youth Y th • In 2004, 73% of AP-treated Medicaid youth and 67% of those privately insured had only conditions that lack an FDA indication for treatment, for any AAP at any non adult age non-adult age. • Externalizing behavioral disorders appear to account for much AP use. use 38% of Medicaid youth and 24% of privately insured were diagnosed with ADHD but not more severe disorders. • The proportion of users diagnosed with bipolar disorder has also grown in both populations. 24 Has Use Also Broadened Among N -Elderly NonNon Eld l Adults? Ad lt ? • Among MA benes age 18 18--64 in our 7 7--state dataset, schizophrenia accounted for 46% of AP users in 2001 and 40% in 2001. Bipolar increased slightly from 9 9.5% 5% to 12 12.4%. 4% Almost oneone-quarter in 2004 were diagnosed with depression or anxiety but not y or bipolar; 22% had range g of other mental psychoses disorders. • Use also broadened among g privately y insured adults ages 1818-64, increasing to .92% of this population in 2006. Bipolar accounted for 27% in 2006 (vs. 20% in 2001) and Sz for 8%. 2001), 8% 33% of users had anxiety or depression without higherhigher-listed dx. dx. 25 AP Use by Hierarchical Diagnostic Group in Medicaid Adults Ages 18 18-64* 64* 2001 , N=198,915 2004 N=249,167 , 46.2% 40.4% Group 2 - Bipolar Disorder 9.5 12.4 Group 3 - Autism or Mental Retardation 0.7 0.7 Group 4 - Anxiety or Depression p 5 - Personality y Disorders ((1st or 2nd Group dx) Group 6 - ADHD 23.4 24.2 04 0.4 03 0.3 0.4 0.4 Group 7 - Substance Abuse 20 2.0 23 2.3 Group 8 - Adjustment Related Disorders 0.6 0.5 Group 9 - Other MH Disorders 7.3 6.9 Group 10 - None of Above 9.7 11.8 Group 1 - Schizophrenia * 7 State Medicaid Data (CA, FL, GA, IL, NY, OH, TX) 26 Use Among Nursing Home Elderly • As in youth, AP use to manage behavioral problems increased among elderly following advent of AAPs. • AP drugs widely used to treat behavioral sx of dementia such as agitation agitation, aggression aggression, wandering wandering, anxiety. • AP use in NH was controversial in the prepre-AAP period and was a focus of 1987 NH reforms (OBRA). Use rates declined about 30% in early 1990s following regulatory reforms, but increased again following the approvals of olanzapine and risperidone,, perceived as “safe” risperidone safe in this population population. 27 Use Among NH Elderly • In mid mid--2000s, evidence accumulated of increased death rates associated with AP treatment of elderly. • In April 2005, FDA issued public health advisory ((“black black box warning”) warning ) finding antipsychotic use to be associated with increased risk for death. MetaMetaanalysis of 17 shortshort-term trials (averaging 88-12 weeks) concluded that relative risk of death increased about 60%, and absolute mortality increased by about 2% for AP treated patients as compared with placebo treated patients. 28 Background Safety concerns for the atypical antipsychotics: Health Canada stated safety concerns for risperidone for increased risk of cerebrovascular events observed in several dementia trials (October 2002) 2002). FDA issued black box warnings of increased stroke risk for specific p AAPs ((April p 2003 - Februaryy 2005). ) FDA issued black box warning for all atypical antipsychotics, with finding of increased risk of all cause death in patients with d dementia ti (A (Aprilil 2005) 2005). IIn ttrials i l averaging i 8 8-12 12 weeks, k relative l ti risk of death increased ~60% vs. placebo. Absolute mortality in drug-treated patients ~4.5% vs. 2.6% in patients randomized to placebo l b ((number b needed d d tto h harm approx. 53) 53). Based largely on observational data, FDA extended black box warning to all APs (June 2008) 2008). 29 Use Among NH Elderly • Other studies confirm this picture and conclude that the risk risk--benefit ratio is generally unfavorable (e.g., CATIE--AD, Schneider meta CATIE meta--analysis, AHRQ evidence report on offoff-label AAP use). Trial results indicate that effectiveness is at best modest. Some reduction in behavioral symptoms (if only via sedation) no evidence of improved cognitive sedation), function. Mechanisms for increased total mortality p unclear but mayy include stroke, falls, pneumonia, AMI (these issues are being examined in a current study). Comparative outcomes across drugs are unclear unclear. 30 AP Discontinuation Trial (DART(DARTAD) • Early in 2009, further experimental evidence of increased mortality associated with AP use among nursing home residents emerged from a UK randomized trial of AP treatment discontinuation. In the DARTDART-AD trial, residents with dementia who had received AP medications for at least 3 months were randomized to continue AP treatment for 12 months or to switch their medication to placebo. TwelveTwelvemonth survival was 70% in the continue treatment group vs. 77% in the placebo group. (Ballard, 2009, Lancet Neurology). 31 AP Discontinuation Trial (DART(DARTAD) • Differences were even g greater in longerlonger g -term followup,, with 24 followup 24--month survival of 46% vs. 71%. • These findings g are p particularly y concerning g since they y suggest that the increased risk identified in the shortshortterm trials in the FDA’s metameta-analysis is exacerbated by long long--term use use, which is believed to be widespread among NH residents in the U.S. • DARTDART-AD also found that for most patients with dementia, AP withdrawal had no overall detrimental effect on functional and cognitive status. 32 AP Use (Last 7 Days) by Hierarchical Diagnostic Group in Nursing Home Residents Age 65+* 1999 2006 N=72,341 N=97,939 Group 1 - Schizophrenia 15.5% 15.3% 4.1 5.4 Group 2 - Bipolar Disorder Group 3 - Dementia & Aggressive Behavioral Symptoms Group 4 - Dementia & Non-Aggressive Behavioral Symptoms Group p 5 - Dementia without Behavioral Symptoms Group 6 - Depression or Anxiety Disorder 19.8 14.1 19.5 19.3 21 4 21.4 28 9 28.9 10.6 11.4 Group 7 - None of Above 9.2 5.7 * Minimum Data Set. Last full non-admission assessment ; long-term stay 33 Results Monthly Proportions of AP use Among Long-term Residents of non Hospital-based Nursing Homes Diagnosed with Dementia Proportion of Full MDS Assessmen nts with AP Us se 50 Observed Predicted Pre-warning trend 45 40 35 30 25 20 34 Results Trends in AP Use Rates By Diagnosis Pro oportion of F Full MDS Ass sessments witth AP Use ♦ Schizophrenia or bipolar disorder 60 ♦ No Dementia * 80 70 ♦ Dementia 1.0 2.3 -0.5 50 40 30 93 9.3 20 10 12.3 * * 2.1 * -5.4 * 0.8 -5.9 0 35 Results Proportion o P of Full MDS A Assessmentts With Drug Us W se Trends in Psychotropic Drug Use Among Residents with Dementia ♦ Antidepressants ♦ Antipsychotics ♦ Antianxiety or Hypnotics 60 50 40 * 9.4 * 30 9.3 20 10 -0.5 0.5 * 6.2 2.1 4.4 * * -5.4 5.4 * 2.6 6.4 0 36 Limitations Analyses are based on MDS assessments rather than claims data. No information on specific AP agents or dosing: Analysis could not explore potential shifts towards: first generation AP agents lower doses. External E t l events t other th than th regulatory l t warnings i may explain the observed trend changes. 37 Discussion While the changes in AP use following the regulatory warnings have been significant, the size of these changes h h has b been small. ll More than 1.5 years after the black box warning for increased all all-cause cause mortality mortality, AP use rates remained significantly higher than at the beginning of the study p period. Substitution with anxiolytics or hypnotics? Future directions: Analysis of claims data will allow to address some of the limitations (dosing, specific APs). 38 Use of Merged MAX and MDS Data to Examine Guideline Consistency of AP Use in NH Elderly • Work in progress progress— —early results presented at CERTs CMS Day, June 2009. • Analyses a yses u utilized ed 20012001 00 -0 04 da data a from o 7 sstates; a es; will be extended to larger set of states and to 2005 data in next phase. • MDS annual assessments provided information on a range of clinical, functional and other resident characteristics MAX data provide information on characteristics. medication use and diagnostic histories; OSCAR data provide facility information. AP use examined i 90 d in day window i d surrounding di assessmentt using i days--supply “calendar”. days 39 E l Results Early R lt • Among NH residents receiving APs APs, guidelineguidelineinconsistent use was more likely among residents who were male, Hispanic, over age 86, or with extensive ADL limitations. • Rates of inconsistent use varied significantly g y across states and were higher in facilities with higher numbers of total deficiency citations and those with hi h rates higher t off physical h i l restraint t i t use, controlling t lli ffor a range of other resident and facility characteristics. Analyses in progress progress, stay tuned tuned... 40 AP Safety and Comparative Effectiveness-Substudies and Data Sources 41 Institutionalized Elderly Analyses •Mortality. •Medical harms. •Functional F ti l outcomes. t 42 Comparative Safety Among Elderly Nursing Home Residents (Analyses In Progress) • Data sources: – Linked Medicaid, Medicaid Medicare, Medicare MDS – 45 states. states • Study cohort: – Medicaid beneficiaries 65+ who initiate antipsychotic py medications during long-term care nursing home stay – beginning with 8 state cohort. • Exposure: – New use of specific APMs; referent group: risperidone – Dose in chlorpromazine equivalents • Outcomes: – All cause mortality; cause-specific mortality: Ca, cv, infect, suicide – Major events: Hosp. for AMI, stroke, pneumonia. 43 Comparative Safety Among Elderly Nursing H Home Residents R id t (A (Analyses l IIn P Progress)) • Covariates: – Age, A sex, race, time, i – Medical conditions, psych conditions, health services intensity – MDS: functional status, cognitive status, behavioral factors • Balance: – Cox PH regression modeling; Propensity score stratification (deciles) • Follow-up: p – 180 days since initiation; censoring: events, d/c of index drug • Analysis: – As treated analysis: rate ratios, stratified by time since initiation – Cumulative risk analysis: risk ratios, risk differences (FECF) • Sensitivity analyses: – Instrumental variable analysis – Residual confounding analysis 44 Comparative Effectiveness of APs i Early in E l Onset O t Schizophrenia S hi h i • Illustrates important potential for MAX for CER in situations where: • RCT evidence is lacking due to ethical, practical and d costt issues. i • Very large study populations needed to study relatively uncommon subgroups (diagnosed with Sz before age 18) and to carefully tailor newnewonset cohorts. Is effectiveness equivalent across drugs? Difficult to examine nonnon-inferiority without large study populations. • Very V early l results l presented d at CMS earlier li this hi month; 2005 data needed for next steps. 45 Drug Abuse and Mood Disorder Hospitalizations Among MA Beneficiaries • Mood disorders are leading cause of psychiatric hospitalization. • 19991999-2000 55-state MAX data used to examine factors that predict mood disorder hospitalization and rehospitalization among MA benes benes. • Among benes with mood disorder, those with comorbid substance abuse (SA) were more than 3 times more likely to have hospitalizations, accounting for 36% of MD hospitalizations. If hospitalized, they were more likely to be readmitted and accounted for 50% of all readmissions. • Results highlight importance of targeting community services to this group to treat SA and MD disorders and prevent decompensation. (Prince, Crystal, AJPH 2009). 46 Suicidality and Antidepressants in Youth Work on this topic also exemplifies importance of large, naturalistic datasets. OBJECTIVE: To estimate the relative risk of suicide attempt and suicide death in severely depressed children and adults treated with antidepressant drugs vs those not treated with antidepressant drugs. DESIGN: Matched casecase-control study. SETTING: Outpatient treatment settings in the United States. PARTICIPANTS: Medicaid beneficiaries from all 50 states who received inpatient treatment for depression, excluding patients treated for pregnancy, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or other psychoses, mental retardation, dementia, or delirium. Controls were matched to cases for age, sex, race or ethnicity, state of residence, substance use disorder, recent suicide attempt, number of days since hospital discharge, and recent treatment with antipsychotic, anxiolytic/hypnotic, anxiolytic/hypnotic, mood stabilizer, and stimulant medications. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Suicide attempts and suicide deaths. 47 Suicidality and Antidepressants in Youth • RESULTS: In adults (aged 19 19--64 years), antidepressant drug treatment was as not significantly significantl associated with ith ssuicide icide attempts attempts. However, in children and adolescents (aged 66-18 years), antidepressant drug treatment was significantly associated with suicide attempts (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.121.12-2.07 [263 cases and 1241 controls]) and suicide deaths (OR, 15.62; 95% CI, 1.651.65infinityy [[8 cases and 39 controls]). ]) • CONCLUSIONS: In these highhigh-risk patients, antidepressant drug treatment does not seem to be related to suicide attempts and death in adults but might be related in children and adolescents. These findings support careful clinical monitoring during antidepressant drug treatment of severely depressed young people. l Source: Olfson et al, Archives of General Psychiatry, 2006 48 In a Medication-Oriented Society With Extensive Drug Promotion, Much Work Needs To Be Done to Understand and Improve Use of Psychotropics. MAX Provides Key E id Evidence Source S for f This Thi Work. W k “Could we up the dosage? I still have feelings.” 49 Q Questions? ti ? scrystal@rci rutgers edu scrystal@rci.rutgers.edu 50 Contact Information Stephen Crystal, Ph.D. Director,, Center for Education and Research on Mental Health Therapeutics Rutgers g University y 30 College Avenue New Brunswick, NJ 08901 voice i 732 732-932-8579 932 8579 fax 732-932-8592 scrystal@rci.rutgers.edu t l@ i t d 51