Construction Minerals in the Baltimore-Washington Metropolitan Area: A Land Management Analysis Kris Wernstedt

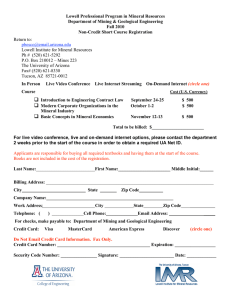

advertisement