Document 11613639

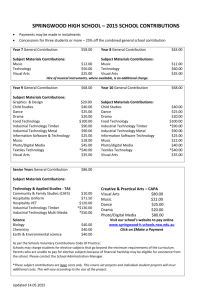

advertisement