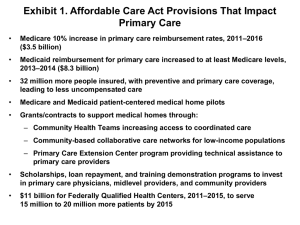

Enhancing the Capacity of Community Health Centers to Achieve High Performance

advertisement