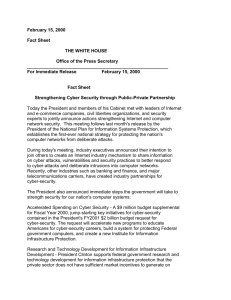

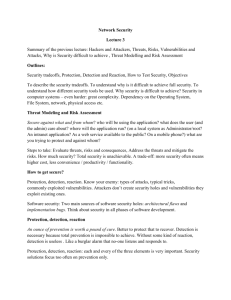

C F RITICAL OUNDATIONS

advertisement