Strengthening CER disparities research and evidence: Using item response theory test

advertisement

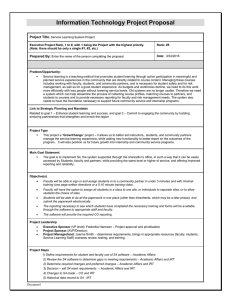

Strengthening CER disparities research and evidence: Using item response theory test equating to combine data from multiple sources and increase sample size and analytical precision Adam C. Carle, M.A., Ph.D. adam.carle@cchmc.org Division of Health Policy and Clinical Effectiveness Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center University of Cincinnati School of Medicine AcademyHealth June 26, 2010: Boston, MA Introduction • Comparative effectiveness research (CER) evaluates which treatments work best for whom under what conditions. • (AHRQ, 2007). • Allows field to determine “the right treatment for the right patient at the right time.” • (AHRQ, 2007). Introduction • Health Disparity: – Differences or gaps in health or health care experienced by one population compared to another. • (AHRQ, 2008). – Differences in the quality of healthcare that do not result from access-related factor or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention. • (Smedley, et al. , 2003). Introduction • Conducting disparities research and CER presents methodological hurdles. • (Carle, 2010). • Minority populations frequently underrepresented in clinical trials and data collection efforts. • (Murthy, et al., 2004; Heiat, et al., 2002) – Often results in small sample sizes. Introduction • Makes it difficult to achieve accurate estimates for minority groups. – Other underrepresented populations too. • Limits ability to accurately assess disparities and evaluate treatment effectiveness across sociodemographic groups. • Could partially address these problems by combining data sources. Introduction • However, independent data collection efforts rarely use identical methods and measures. • And, variation in study administration and measures across data sources makes it difficult to compare estimates or combine data. IRT Test Equating • Item response theory (IRT) test equating provides a method for combining data across collection efforts. – Administered at separate times to different populations. • e.g., Two separate studies. – Across different but related measures. • e.g., Two different measures of depression. • Also called linking. IRT Test Equating • Scales (“tests”) measure an indirectly observed construct. – Latent trait. • Also labeled latent construct or variable. • Frequently notated as “theta” (θ). • Examples. – Pain. – Care experience. – Income. – Special health care needs status. IRT Test Equating • If we knew people’s underlying latent trait values, we could predict their response to a scale. – Any scale. • IRT models result in parameters allowing use of people’s responses to estimate latent trait values. • With latent trait estimate, can predict “score” someone would receive on different scale measuring same trait. IRT Test Equating • To do this, we must equate (link) the IRT parameters. – Put them on the same metric. • Once we have linked the IRT parameters, we can combine samples more validly. – Can report in the raw metric of one of the scales. – Or, can report on the latent trait metric. • Typically standard normal. IRT Test Equating • Some (but not all) requirements: – Studies have used a measure of the same trait. • e.g., Special health care needs status. • Can be two different administrations of same scale. • Or, can be different scales entirely. – Ideally, scales include at least some common questions. – Can fit IRT model for both scales. – Other statistical requirements. • Kolen & Brennan (2004) provide extensive details. IRT Test Equating • Given the properties of IRT modeling, a linear function should relate the two scales. • 1 A 2 B • Slope (A) and intercept (B) are the linking coefficients. IRT Test Equating • Same coefficients also link individual IRT parameters. • a j1 • a j2 A b jk1 b jk 2 B ? Current Study • Utilized test equating to link data from: – Medical Expenditures Survey (MEPS) – Ezzati-Rice, et al., 2008. – 2005-2006 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN) – Blumberg, et al., 2009. • Both surveys include the CSHCN Screener . – Bethell, et al., (2002) & Carle, et al. (2010). • Can fit IRT model to CSHCN Screener. – Screener measures condition complexity. – Carle et al. (2010). Current Study • Well known difference in CSHCN prevalence result across surveys. – MEPS: 12.5%. – NS-CSHCN: 5.8%. – Bethell, et al. (2002). • May result from survey administration difference. – Could cause differential responses at same trait levels. Current Study • MEPS includes more extensive health measures beyond CSHCN Screener. • Cannot estimate IRT model independently for Hispanics in just MEPS data. Current Study • Used simultaneous calibration to link CSHCN Screener IRT modeling. – Addresses all of these issues! • Compared performance and usability across: – Mplus (5.2: Muthén & Muthén, 2010). – PARSCALE (4.1: Muraki, 2003). – MULTILOG (7.03: Thissen, 2003). Current Study • Mplus: Used anchor item method. – Links scales by constraining one (or more) item’s to equality across administrations. • Other possibilities exist. • PARSCALE: Constrained average of location parameters to equality across scales. – Only option in PARSCALE. • Multilog: No easily implemented simultaneous estimation/calibration method. – Can do separate calibrations and then equate using separate calibration methods. – Did not consider Multilog further here. Methods: MEPS • MEPS: Five-round longitudinal panel survey. – Data come from 2004-2005 Panel 9 sample, round 2. • Multistage, complex sampling design. – Ezzati-Rice, et al., 2008 for details. • Represents non institutionalized US population. • Included individuals who self identified Hispanic. – n = 1,752. • Relatively lengthy, especially compared to NSCSHCN. Methods: NS-CSHCN • NS-CSHCN: Cross section survey. – Data come from 2005-2006 NS-CSHCN. • Multistage, complex sampling design. – Blumberg, et al., 2009 for details. • Represents non institutionalized US childhood population. • Current study used all individuals who self identified as Hispanic. – n = 51,581. • Methods • CSHCN Screener: • Series of questions determine whether a medical, behavioral, or other health condition lasting at least 12 months causes a child to: – 1) Need prescription medication(s). – 2) Need more health or educational services. – 3) Experience limited ability to perform activities. – 4) Need specialized physical, occupational, or speech therapies. – 5) Have a behavioral, emotional, or developmental condition requiring treatment or counseling. Methods • Placement of Screener questions: – NS-CSHCN: First questions asked of all respondents. – MEPS: Embedded far into the survey. • Placement could easily result in differential item functioning and require linking. • Schwarz and colleagues have shown extensively how even simple prompts change relationships among questions. – e.g., Schwarz, 1999a, 1999b; Smith, Schwarz, et al. 2006. Results • Raw score results among Hispanics only. – MEPS: • 12.55% CSHCN. • 87.45% non-CSHCN. – NS-CSHCN: • 5.87% CSHCN. • 5.78% non-CSHCN. • Strikingly different estimates. Results • IRT linking results among Hispanics only. – Mplus MEPS: • 7.85% CSHCN. • 94.22% non-CSHCN – Mplus NS-CSHCN: • 4.42% CSHCN. • 95.58% non-CSHCN. • Estimates much closer in alignment. Results • IRT linking results among Hispanics only. – PARSCALE MEPS: • 6.58% CSHCN. • 93.42% non-CSHCN – PARSCALE NS-CSHCN: • 5.78% CSHCN. • 94.22 % non-CSHCN. • Estimates much closer in alignment. Discussion • Measurement differences can lead to erroneous disparities estimates. – Can result from measurement error. • Small sample sizes increase likelihood of error. • Here, it appears MEPS small sample size limits the ability to accurately estimate CSHCN prevalence among Hispanic families. • Likewise, survey introduction and format (length) may influence participants responses. Discussion • IRT linking allows one to overcome one of the methodological hurdles often present in disparities research and CER. • Several linking methods and software programs exist. • Simultaneous linking/ calibration ideal and used here. Discussion • Advantages to IRT linking: – Allows one to compare scores on scales: • From different samples. • With different items. • “Borrows” information from each scale to reduce estimation error. – Conversions are independent of groups used to obtain them. • Basic property of IRT. – More precise than classical test theory methods. Discussion • Mplus allows much greater flexibility relative to all other available programs. – Allows multiple ways of linking scales. – Allows multidimensional models. – Allows very complex models, as appropriate. – Can handle complex survey designs. • Mplus much more user friendly than other available programs. – PARSCALE and Multilog “persnickety” (at best). – However, even Mplus isn’t overly user friendly. • i.e., Not point and click. Discussion • Many possible applications exist. • Multidimensional linking. • CAHPS Cultural Competency project. • Two separate projects used new set of cultural competence items to determine items’ psychometric properties. • Alone, sample sizes too small to examine among subgroups. – Linking allowed subgroup examination. Conclusion • IRT linking can powerfully overcome on of the many hurdles in disparities research and CER. • Increased accuracy will allow us to better understand and eradicate health disparities. Strengthening CER disparities research and evidence: Using item response theory test equating to combine data from multiple sources and increase sample size and analytical precision Adam C. Carle, M.A., Ph.D. adam.carle@cchmc.org Division of Health Policy and Clinical Effectiveness Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center University of Cincinnati School of Medicine AcademyHealth June 26, 2010: Boston, MA