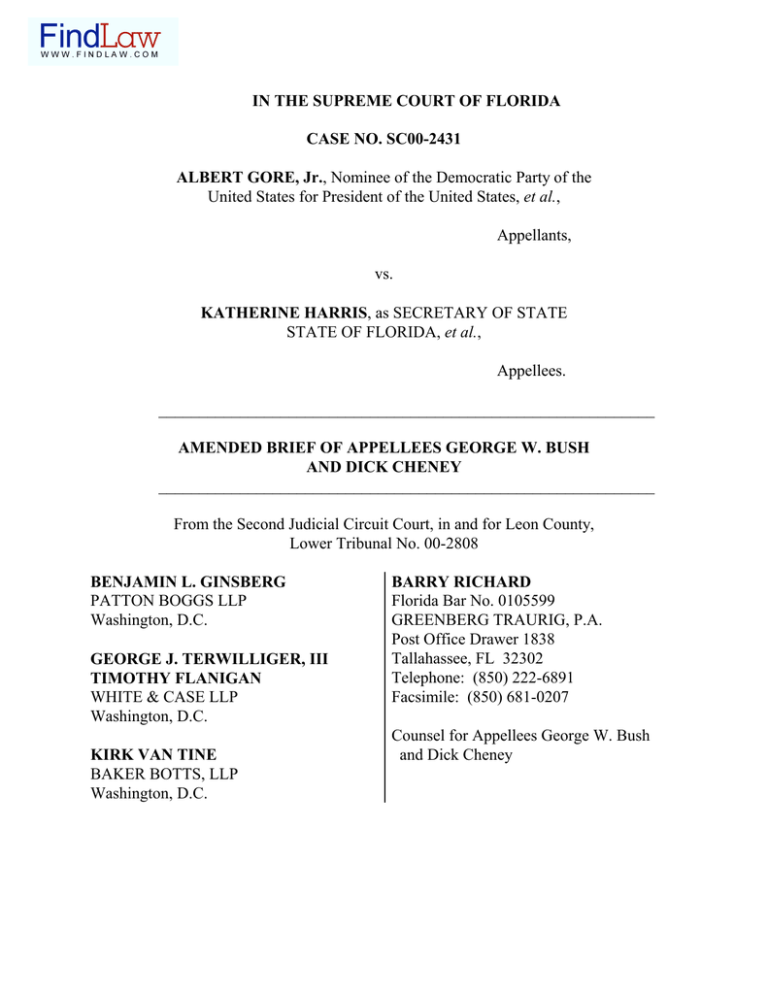

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA CASE NO. SC00-2431 ALBERT GORE, Jr.

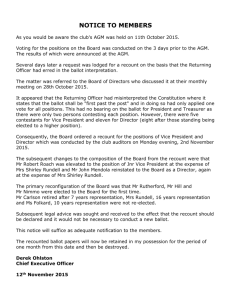

advertisement