Heavy Metal: It’s More than Rock Cleveland Section American Chemical Society

Heavy Metal: It’s More than Rock

An Educational Demonstration Package

Prepared by the

Cleveland Section

of the

American Chemical Society

National Chemistry Week 1997

Back in 1886, Charles Hall in nearby Oberlin, Ohio, developed an inexpensive way to extract aluminum (considered an expensive and rare metal) from its ore. This year, 1997, the

American Chemical Society, declares this discovery a NATIONAL HISTORIC CHEMICAL

LANDMARK! Also, 1997 marks the 10 th anniversary of National Chemistry Week. The traditional 10 th anniversary gift is aluminum!

This National Chemistry Week program celebrates metals and provides a history of metals by discussing “unreactive” metals like copper that early peoples found lying around to today’s special and exotic metal alloys. Hands-on activities help children in grades 2 - 5 appreciate the chemistry of metals by studying magnetism, electroplating, corrosion, etc. Students will explore the most fascinating properties of metals, become magicians and make one metal disappear while making another appear, and create metals with electricity.

Metals surround us and define our world.

Celebrated November 2 - 8, 1997.

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

Overview

Check-Lists

Opening Session

Malleability of Metals

Melting of a Metal

Reactivity of Metals

Reactivity of Calcium

Magnetism Demonstration

Corrosion Demonstration

Cleaning Silver Easily

Forming Copper from Aluminum

33

37

A Fruitless Battery (and

Optional

- Fruit Battery) 41

Electroplating Copper 45

19

23

26

29

6

10

13

16

Page

3

4

A Metal That Remembers Demonstration

Closing Session

Appendix - Kit Contents and Activities To Do

On-Site Prior to Demonstration

49

52

53

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 2

Acknowledgments

Demonstrator’s Guide

Acknowledgements

This presentation is the result of many dedicated and talented volunteers. Charlie Beck of the

Cleveland Section Archive’s Committee noticed the amazing coincidence of the tenth anniversary of NCW (traditional gift of aluminum) and the 100th anniversary of Charles Hall’s development of an economical method of obtaining metallic aluminum. His suggestion to somehow tie the two anniversaries together led to this year’s theme. A small core group met to develop and generate the basic experiments. This group included Nick Baldwin, Betty

Dabrowski, Fen Lewis, Rich Pachuta, Marcia Schiele, and Mike Setter. The demonstration kits were put together through a long day’s work by David and Gail Ball, Betty Dabrowski, Dave

Ewing, Paula Fox, Louis Kuhns, Helen Mayer, Kathyrn Miller, Rich Pachuta, Susie Rolland,

Macia Schiele, Mike Setter, Shermila Brito Singham, and Stephanie Stegal. The instruction set is the result of Susie Rolland’s caring ministrations. Of course, the true success of this presentation does not lie with this document or the dozens of demonstration kits. The true success of this demonstration program is due to the efforts of each and every one of the volunteer presenters who breath life into the presentation to make it come alive for the children of geater

Cleveland. There is little left to take credit for except for the spearheads of the entire process --

Mike Setter and Betty Dabrowski.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 3

Overview

Demonstrator’s Guide

Overview

This year’s National Chemistry Week demonstrations are a trip through time. We will outline the progress of civilization and science by studying the development of metal technology. While the Hall process for aluminum provided the inspiration for the activities, it is slightly impractical to demonstrate molten salt electrolysis at area libraries. Instead of duplicating Hall’s pioneering work, the activities in this year’s program trace the development of metals throughout the history of man, culminating in some aqueous electroplating. Along the way students will get an opportunity to study some interesting metal properties:

ductility

alloy formation

chemical activity

magnetism

corrosion

electrochemistry

electroplating

exotic alloys

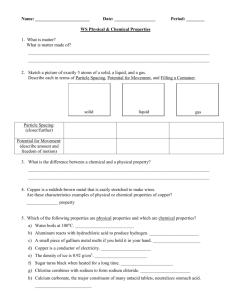

How Experiment Write-ups are Organized

Each experiment write-up is divided into seven different parts:

Background and Set-Up Information for Demonstrators

Materials for This Experiment - Students

Materials for This Experiment - Demonstrators

Experiment Demonstration Pre-Work Set-Up

Demonstration Instructions

Experiment Conclusions & Answers

Additional Information If Needed

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 4

Overview

Demonstrator’s Guide

Presentation Overview

This section describes the basic presentation technique used during the demonstrations. This is a guideline only as some experiments are different. Make sure you follow the instructions given in each experiment.

1. Introduce experiment.

2. Do your demonstration piece.

(2):

Note (1): Most experiments require you to perform the experiment to show the students what to do on their own.

The different experiments are related by the story you tell about the history and properties of metals.

3. Have the students do their experiment.

Note: For some experiments your demonstration and the students hands-on work are nearly simultaneous. You are leading them as they perform the experiment..

MAKE SURE TO FOLLOW ALL DIRECTIONS IN EXPERIMENTS

• A couple of the experiments require you to start them early in the program and finish them later. Do not forget to return to these experiments before the program ends.

• Some experiments have special safety concerns due to the materials being used. These are listed in the section for that experiment.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 5

Check-Lists

Demonstrator’s Guide

Demonstration Check-Off List

The next few pages list suggested activities to complete for the program.

Activities To Do Before You Go To The Demonstration

Read through this information packet to familiarize yourself with the experiments.

Collect the materials you need to bring with you to the demonstration:

This packet

The demonstration kit

1 gallon jug for waste water collection

1 roll of paper towels

Sharpie-type pen

13 new pennies

OPTIONAL - 7 items of fruit or vegetables. These may be 7 individual plums (or peaches, or melons.) or 7 separate pieces of a plum (or peach, melon)

1 kitchen knife

1 large garbage bag

Contact the children’s librarian:

Ask the room to be arranged with 6 tables around a front table

Ask to have 5 chairs around each of the 6 tables

Ask for all the tables to be covered with newspapers

Ask if they have a microwave, or some way to boil a couple of cups of water

Note: If the library cannot provide a way to boil water, bring boiling water to the library in an insulated container

When Complete

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 6

Check-Lists

Demonstrator’s Guide

Activities To Do When You Get To The Library

Introduce yourself to the children’s librarian.

Ask the librarian how many students are pre-registered.

Confirm that there are 6 student tables and 1 demonstrator’s table.

Confirm that all tables are covered in newspape.r

Set out the individual items for each experiment on the students’ tables.

Complete Demonstration Pre-Work Set-Up for all demonstrations:

Malleability of Metals

Melting of a Metal

Reactivity of Metals

Reactivity of Calcium

Magnetism Demonstration

Corrosion Demonstration

Cleaning Silver Easily

Forming Copper from Aluminum

A Fruitless Battery (Optional - Fruit Battery)

Electroplating Copper

A Metal that Remembers Demonstration

Note: This set-up is estimated to take 45 minutes.

Set out the literature.

When Complete

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 7

Check-Lists

Demonstrator’s Guide

Activities To Do During The Demonstration

Welcome the students and parents as they enter the room.

Give each student a Metal Quiz when they enter the room.

Assess number of students per table and adjust to 3 - 5 per table.

Note: If you have extra tables, keep them empty.

Complete the Opening Session introduction.

Perform metal history demonstrations and activities:

Malleability of Metals

Melting of a Metal

Reactivity of Metals

Reactivity of Calcium

Magnetism Demonstration

Corrosion Demonstration

Cleaning Silver Easily

Forming Copper from Aluminum

A Fruitless Battery (Optional - Fruit Battery)

Electroplating Copper

A Metal that Remembers Demonstration

Complete the Closing Session information.

Remember to complete the observation of corrosion.

Remember to assess cleanliness of the silver.

Tell the students there is literature to pick up.

Thank everyone for coming.

0.5 min.

0.5 min.

Timing

-

-

-

2 min.

2 min.

3 min.

7 min.

5 min.

7 min.

5 min.

5 min.

Total Time:

49 min.

5 min.

3 min.

8 min.

3 min.

4 min.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 8

Activities To Do Immediately After The Demonstration

Transfer all liquids to the 1 gallon waste jug.

Transfer all solids to the garbage bag.

Remove newspapers from the tables and put in the garbage bag.

Give any left over literature to the librarian.

Check-Lists

Demonstrator’s Guide

When Complete

Activities To Do Once You Get Home

Pour waste liquid from 1 gallon jug down the drain.

Put garbage bag in the trash.

Clean and dry all vials.

When Complete

Note: All materials are typical household products. They can be safely disposed of in the manner indicated above.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 9

Opening Session

Demonstrator’s Guide

Opening Discussion

Introductions

Do the following:

Introduce yourself as a chemist.

Introduce the American Chemical Society as the largest organization in the world devoted to a single profession.

Introduce National Chemistry Week - what it is and why we do it.

(Hint: it is a nationwide event put on by volunteers like you to let non-chemists know about chemistry and how chemistry and chemists influence their lives.)

What is Chemistry and Chemicals?

Do the following:

Explain that chemistry is the study of everything around them.

Ask for volunteers to name some chemicals. Then ask more volunteers to name something that isn't a chemical.

Remember: everything around us is a “chemical”.

Be very careful in correcting them. Encourage their participation while explaining that their idea really is a chemical.

What Do Chemists Do?

Ask the participants to tell you what a chemist does, what a chemist looks like.

Note: Be prepared for some strange and funny answers. Try not to laugh, cry, or get offended.

Tell them BRIEFLY and in simple terms what you do as a chemist.

Note: This should last no more than 1 minute. Remember to leave the physical chemistry lecture and the “big” chemistry words at home!

Tell them that chemists use their knowledge to answer questions about the world around them. This is very exciting, as they will soon see.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 10

Opening Session

Demonstrator’s Guide

Demonstration Introduction

Get Them Roped Into Traveling through Time with Metals

Do the following:

Ask them if they have ever seen the Back to the Future movies.

Tell them that they can travel through time much easier than Doc Brown by becoming chemists for the next hour. Ask them if they want to take the trip with you (hopefully they affirm with glee).

Set the Story of Time and Metals

Do the following:

Ask them: What Doc Brown and Marty used to travel through time in?

(Answer: a customized DeLorean sedan.)

Ask them: What makes the Delorean look different from other cars?

(Answer: it’s made from stainless steel, a different type of metal from most cars.)

Tell the story:

Just as Doc Brown’s stainless steel car helped him travel through time, we will use metal to journey through time. Instead of using just one metal and a lot of complicated gadgets, we will use many metals and a lot of chemistry.

Much of our modern world is made of metal, from the cars we drive, to the chairs we sit in, to the support for the buildings. All are made from metal. Without metals, our world would be a much different place. ( You can ask them to look around the room and name some metals.) Our surroundings would have to be much like the

Flintstones’ where everything is made from wood and stone. However, history records a much different Stone Age from the one that the Flintstones lived in. There was no civilization, there were no houses, and certainly none of the fancy household appliances that make Fred and Wilma’s lives so easy.

We will journey back in time to that world without metals. Our only hope of coming back to the future, the future where we live, is metal. Because metal, even heavy metal, is so much more than rocks.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 11

Opening Session

Demonstrator’s Guide

Introduce the Items on the Tables

Do the following:

Tell them that the objects on their tables will allow them to travel through time to explore the world of the past.

Note: If anyone objects to or questions the concept of time travel, assure them we will not be violating any laws of nature and we will be back to the present within the hour.

Ask them not to touch anything on the table until you explain what to do.

Tell them that they are now back in the Stone Age, before anyone knew what a metal was.

Tell them that we are going to start our trip back to the future.

Tell them that they will examine various properties of metals.

Tell them that this is the first step in the scientific method: observation.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 12

Malleability of Metals

Demonstrator’s Guide

Malleability of Metals

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

The Malleability of Metals is one of the first properties that sets metals apart from the rock and wood materials of the ancient world.

•

Pieces of two thin foils are placed over new pennies and a rubbing made. Both foils develop images, but they are not equally sharp.

•

The students will test 2 foils; the demonstrator will test 2 foils.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

•

6 pieces of aluminum foil (2” X 2” X 0.001”) (1 on each table)

• 6 pieces of copper foil (2” X 2” X 0.001”) (1 on each table)

•

12 new pennies (2 on each table)

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

•

1 piece of aluminum foil (2” X 2” X 0.001”)

• 1 piece of copper foil (2” X 2” X 0.001”)

•

1 new penny

Malleability of Metals Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Remove 7 pieces of aluminum foil from bag marked “Al Mall” in demonstrators kit.

Place one each on the students’ tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Remove 7 pieces of copper foil from bag marked “Cu Mall” in demonstrators kit.

Place one each on the students’ tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Place two new pennies on each of the students’ tables.

Place one new penny on the demonstrator’s table.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 13

Malleability of Metals

Demonstrator’s Guide

Malleability of Metals

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

As ancient man was walking around the caves and plains of his world, he occassionally noticed very shiny rocks sticking out of the ground.

However, unlike the shiny gems and minerals, some of these shiny rocks could be beaten with a rock without breaking. They changed their shape as they were beaten.

When ancient man began beating these shiny rocks into tools, he left the Stone Age and entered the Copper Age about 12,000 years ago.

Let’s see how this was done.

Perform the Malleability of Metals Simultaneously With the Students

Part I - Testing the Metals

Do the following:

Pick up the demonstrator’s piece of copper foil.

Tell the students to look on their table and find the copper and aluminum foil.

Pick up your penny.

Tell the students to find both their pennies.

Place your penny on the table and your copper foil over the top of it.

Tell the students to put a different foil over both of their pennies.

Rub your finger back and forth over the foil, pressing down on the penny.

Tell the students to do the same with both of their foils.

While the students are doing this, repeat the procedure with your aluminum foil.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 14

Malleability of Metals

Demonstrator’s Guide

Part II - Interpreting the Results

Do the following:

Ask the students to compare the rubbings on each of the foils. Which one has the sharpest image of the penny?

Note: The aluminum foil should have a rough image of the penny. The copper foil should have a much clearer image.

Ask the students which of the metals would have been easiest for ancient man to beat into tools?

Ask the students which of the metals would have made the hardest tools?

Note: If the pennies are not all new, the differences in the sharpness of the pennies may mask the differences in the foils.

Malleability of Metals Conclusions

Tell the students the following:

Copper can be found lying on the ground.

Stone Age man found some of this copper and noticed that it could be easily shaped just as we did.

We have now stepped from the Stone Age into the Copper Age, about 12,000 years ago.

Copper Age man now makes some of his tools from copper.

However, the softness of copper that makes it easy to make into tools causes problems.

The tools are easily bent when used. Copper could not be made into plows, knifes, or swords.

A different type of metal needed to be developed for these tools.

We have to make another jump forward in time.

Additional Information If Needed: Malleability of Metals Technical Background

• The malleability and ductility of metals continues to be one of their most important properties today. At times the softness of copper is needed, such as for wiring. At other times the rigidity of hardened steels and other alloys is required.

•

Malleability is the ability of a material to be beaten into a flat sheet.

• Ductility is the ability of a material to be drawn into a wire.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 15

Melting of a Metal

Demonstrator’s Guide

Melting of a Metal

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

The Melting of a Metal experiment involves the process of creating an alloy by melting two metals together.

•

A fusible alloy with a low melting point is dropped into a cup of hot water.

• A stirrer is used to show that the metal is now a liquid.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

•

None - this demonstration is performed solely by the demonstrator.

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

• boiling hot water

•

1 insulated styrofoam cup

Note: If you brought boiling hot water in an insulated container, you may use it instead of the styrofoam cup.

• 1 clear, 8 oz. plastic cup

•

1 plastic stirrer

• 1 piece of Onion’s Fusible Alloy

Melting of a Metal Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Boil some tap water at the library as near presentation time as possible.

Pour about 5 oz into an insulated styrofoam cup for storage.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 16

Melting of a Metal

Demonstrator’s Guide

Melting of a Metal

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

All of the other metals (gold and silver) that ancient man could find lying around on the ground were as soft as copper.

Unless new metals could be found, or made, durable tools were impossible.

After a campfire one morning, someone found a new shiny rock in the ashes. This rock looked like copper, but was much harder.

When ancient man discovered the secret of making this new rock on demand, the first man-made chemical was created.

Perform the Melting of a Metal For the Students

Do the following:

Pick up the piece of Onion’s Fusible Alloy.

Show it to each table and have the students verify that it is solid.

Pour the boiling hot water into the clear 8 oz. plastic cup.

Drop the Onion’s Fusible Alloy into the water.

Use the plastic stirrer to demonstrate that the metal is now a liquid rolling around on the bottom of the cup.

Take the cup to each table and have the students verify that the alloy is now a liquid.

Melting of a Metal Conclusions

Tell the students the following:

Our Copper Age campfire got hot enough to melt copper and some tin that was lying on the ground.

When two metals melt together, they become liquid and mix.

When the liquid cools, it forms a new substance called an alloy.

When copper and tin melt together the alloy they form is called bronze.

The new metal in our Copper Age campfire was the alloy bronze.

Bronze was soft enough that it could be beaten into new shapes and it was hard enough that the tools would last.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 17

Melting of a Metal

Demonstrator’s Guide

We’ve made another step back to the future by entering the Bronze Age, about 5000 years ago.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 18

Melting of a Metal

Demonstrator’s Guide

Additional Information If Needed: Alloy Technical Background

• Onion’s Fusible Alloy is an alloy of bismuth (~50%), lead (~30%), and tin (~20%).

•

Onion’s Fusible Alloy melts at 92

°

C.

•

Onion’s Fusible Alloy is used in automatic sprinkler systems. The alloy is formed into a piece that prevents the flow of water. When a fire heats the alloy hot enough, it melts. The shape changes. The water then flows to put out the fire.

• Bronzes have a range of composition from 10% tin to 90% tin, depending on the use.

•

The melting point of copper is 1080

°

C. Tin has a melting point of 230

°

C. Bronzes have a melting point from 1000

°

C to 440

°

C. All of these are too hot to handle safely in the library.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 19

Reactivity of Metals

Demonstrator’s Guide

Reactivity of Metals

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

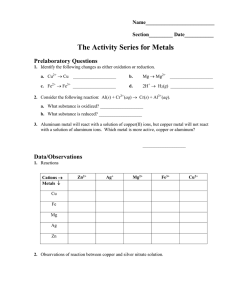

The Reactivity of Metals involves observing the amount of bubbles produced when three different metals are placed into a mild acid solution.

•

Galvanized roofing nails, magnesium strips, and copper wire are placed into solutions of 2% muriatic acid.

•

The students will test all three metals; the demonstrator will test all three metals.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

• 6 pieces of solid copper wire (1 on each table)

•

6 galvanized roofing nails (1 on each table)

• 6 magnesium strips (1 on each table)

•

18 clear 4 oz. plastic cups containing 2% muriatic acid (3 on each table)

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

• 1 piece of solid copper wire

•

1 galvanized roofing nail

• 1 magnesium strip

•

3 clear 4 oz. plastic cups containing 2% muriatic acid

REMEMBER - 2% MURIATIC ACID IS 0.5 M HCl.

DO NOT LET STUDENTS PLAY WITH THE ACID.

Note: In case of a spill, wipe it up immediately with paper towels and clean with wet paper towels.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 20

Reactivity of Metals

Demonstrator’s Guide

Reactivity of Metals Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Place 1 galvanized nail, 1 copper wire, and 1 magnesium strip onto each student table and the demonstrator’s table.

Remove 21 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups from the demonstrator’s kit.

Label them “React”.

Add enough water to the vial with only 5 mL 6 M HCl * to completely fill it.

Thoroughly mix the HCl and water.

Evenly distribute the HCl among the 21 cups.

Add enough water to each of the cups to fill them slightly less than _ full.

Place 3 cups on each student table and the demonstrator’s table.

*Note on Preparation: You can purchase muriatic acid at a hardware store or prepare a weak solution of hydrochloric acid (HCl). Note that the 6 M HCl will also be used in the Corrosion

Demonstration on page 29.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 21

Reactivity of Metals

Demonstrator’s Guide

Reactivity of Metals

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

Living in the Bronze Age is much easier than the Copper Age.

Our tools last much longer and we now have sharp knives for cutting.

But all is not well. Tin, for alloying with copper, is in very short supply lying around on the ground.

This makes the tools very expensive.

Most metals are not found in nature in their pure state. They are chemically combined with other materials into minerals and rocks called ores.

Why can some metals be found pure in nature, while others are only found as ores?

In order to get back to the future, we need to find the answer.

Our next experiment should help us.

Perform the Reactivity of Metals Simultaneously With the Students

Part I - Testing the Metals

Do the following:

Tell the students to find their three plastic cups marked “React”.

Tell the students that the cups contain a dilute acid solution.

Tell the students to pick up their copper wire and carefully place it in one of the plastic cups.

Demonstrate this with your copper wire as you are telling them what to do.

Tell the students to do this with their magnesium strip, and their galvanized nail, using different plastic cups each time.

Do the same thing yourself while the students are doing it.

Part II - Observing the Results

Do the following:

Tell the students to describe what happened when the metals were placed in the acid.

Ask the students if all three metals behaved the same way.

Ask the students which of the three metals bubbled the most. The least?

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 22

Reactivity of Metals

Demonstrator’s Guide

Material copper wire galvanized nail magnesium strip

Observation no bubbles bubble slightly bubble vigorously

Reactivity of Metals Conclusions

Tell the students the following:

The more vigorously the metal bubbles, the more it likes to be combined with something else as a mineral or ore..

The more strongly a metal likes being combined with other things, the harder it is to extract it.

Metals that could not be found lying pure on the ground had to be extracted from ores.

Some metals could not be extracted from their ores until the last 100 years.

Do the following:

Ask the students if this explains why copper was often found lying pure on the ground and some metals like the zinc coating on the galvanized nail never are found pure in nature.

Additional Information If Needed: Reactivity of Metals Background

• The bubbles formed above indicate that a chemical reaction is occuring and hydrogen gas is being formed.

• The date of discovery of the metallic elements closely follows the development of furnace technology. As furnaces became capable of higher and higher temperatures, more reactive elements could be extracted from their ores.

•

The entropy change of a metallic element combining with gaseous oxygen to become the oxide is nearly constant for all metallic elements. The free energy change for this reaction varies from element to element primarily due to the differences in the enthalpy of the combustion reactions.

•

Conversely, the temperature that an oxide must be raised to release the oxygen follows the enthalpy of the combustion reaction.

•

The highest attainable temperature in a kiln or furnace in any age can be estimated by metallic elements discovered at that time and their enthalpies of combustion.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 23

Reactivity of Metals

Demonstrator’s Guide

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 24

Reactivity of Calcium

Demonstrator’s Guide

Reactivity of Calcium

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

Calcium is the most reactive metal that we can safely demonstrate in the libraries. It reacts vigorously with plain water. Acid is not needed to cause the reaction.

•

A small piece of calcium turnings is added to a cup of water and the reaction is observed.

• The students will each use one piece of calcium as will the demonstrator.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

•

6 pieces of calcium turnings (1 on each table)

• 6 clear 8 oz plastic cups (1 on each table)

•

Tap water

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

• 1 piece of calcium turning

•

1 clear 8 oz plastic cup

• Tap water

Reactivity of Calcium Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Remove 7 clear 8 oz. plastic cups from demonstrator’s kit, and label them WATER with the

Sharpie-type pen.

Put 1 cup on each of the students’ tables.

Put 1 cup on demonstrator’s table.

Fill all cups with about 6 Tblsp. (100 ml) of tap water.

Put the bag marked “Calcium” containing all 7 pieces of calcium turnings by the demonstrator cup.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 25

Reactivity of Calcium

Demonstrator’s Guide

Reactivity of Calcium

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

Some metals are even more reactive than the magnesium. They will react directly with water.

They don’t need acid to react.

This is one metal that was not discovered until 1808. Let’s see why it took so long to discover it.

Perform the Reactivity of Calcium Simultaneously With the Students

Part I - Testing the Reactivity of Calcium

Do the following:

Give one piece of calcium turning to each table and tell them just to look at it.

Pick up the clear 8 oz. plastic cup with water, and tell the students to find their cup like yours.

Drop the calcium turning into the water, and show the students what happens.

Tell the students that they will drop their calcium into the water also, but that they should not put their face directly over the cup.

Tell the students to drop their calcium turning into their plastic cup.

Part II - Observing the Reactivity of Calcium

Do the following:

Tell the students to observe the reaction.

Ask the students if calcium is more or less likely than zinc to be found combined with another material.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 26

Reactivity of Calcium

Demonstrator’s Guide

Reactivity of Calcium Conclusions

Do the following:

Ask the students if they think that calcium could ever be discovered lying pure on the ground.

Ask the students what would happen if some pure calcium were left outside when it rained.

Collect each of the plastic cups containing the calcium waste to prevent spillage.

Tell the students the following:

The name of this metal is calcium. It comes from common lime (the fertilizer, not the fruit).

Lime has been used for thousands of years. Calcium was not extracted from lime until 1808.

1808 is getting ahead of ourselves. We’re not ready for such a huge leap back to the future.

Now that we know why some metals can be found lying on the ground and some can’t, we can start working out ways to obtain metals that aren’t lying on the ground.

To do that, we need to examine the most important metal of all, iron. (See next experiment.).

Additional Information If Needed: Reactivity of Calcium Technical Background

•

Calcium is the fifth largest component of the earth’s crust. The reason it was not discovered until so recently was not due to its rarity on earth.

•

Calcium is never found uncombined in nature. It is usually found combined with oxygen.

• Calcium is a major component of shells, bones, and teeth.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 27

Magnetism Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

Magnetism Demonstration

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

The Magnetism Demonstration involves one of the most interesting properties of metallic iron.

•

An ordinary iron nail is rubbed against a magnet. The nail is then used as a compass.

• The students will test 1 iron nail; the demonstrator will test 1 iron nail.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

•

6 iron nails (1 on each table)

• 6 sections of a wine bottle cork (each with a nail through it) (1 on each table)

•

6 clear, 8 oz. plastic cups (1 on each table)

• tap water

•

6 1 cm X 1 cm pieces of magnets (1 on each table)

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

• 1 iron nail

•

1 section of a wine bottle cork (with the nail through it)

• 1 clear, 8 oz. plastic cup

• tap water

• 1 National Chemistry Week button

Magnetism Demonstration Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Place one iron nail-cork combination on each of the student tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Put one clear, 8 oz. plastic cup on each of the student tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Pour about 5 oz. of tap water into each of the seven cups.

Put one of the small magnets on each of the student tables.

Put the NCW button on the demonstrator’s table.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 28

Magnetism Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 29

Magnetism Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

Magnetism Demonstration

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

Bronze Age man learned how to separate iron from iron ore and create steel.

Although the process has become more efficient over the centuries, the same basic process of heating iron ore to very high temperatures is still used in Cleveland to make steel today.

Iron provides many advantages over bronze. It could be made much harder so that it could be used to make many shapes and tools.

Iron is also much more abundant on earth than either copper or the tin needed to make bronze.

When the secret to separating iron was uncovered, the Iron Age of history began, about 4500 years ago.

One of the major uses of iron was (and continues to be) making weapons like knives, daggers, swords, and spears. One of the ores of iron is called lodestone. It has the very strange property of attracting pieces of iron to it. A king of one of the ancient lands heard of this powerful rock and decided to make use of its abilities. In those days, a king was often the most powerful warrior. This king wanted to make sure that no other warriors tried to attack him. He had the doorway to his throne room made from a huge piece of lodestone. Any warriors who entered the room carrying the new iron weapons were immediately stuck to the side of the door. The world’s first metal detector.

Lets examine a more peaceful use of this property.

Perform the Magnetism Demonstration Simultaneously With the Students

Part I - Test the Iron Nail’s Property

Do the following:

Pick up your iron nail in the cork section.

Tell the students to do the same.

Float the nail and cork in the plastic cup.

Tell the students to do the same.

Move the NCW button around the outside of the plastic cup and observe the movement of the nail.

Have the students take turns using the small magnets to move the nail.

Ask the students if the nail points in any one direction when the small magnet is removed.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 30

Magnetism Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

Part II – Making a Compass

Do the following:

Pull your nail and cork from the plastic cup.

Have the students do the same thing.

Rub the flat section of the cork back and forth several times over the magnet attached to the back of the NCW button.

Repeat this for each of the tables using your NCW button.

Note: The small magnets are not strong enough to magnetize the nail in the cork.

Float your nail and cork back in the plastic cup, and have the students repeat your action.

Move the NCW button around the outside of the plastic cup and observe the movements of the nail.

Have the students take turns using their magnets to do the same thing.

Ask the students if the nail points in any one direction when the magnet is moved away from the cup.

Magnetism Conclusions

Tell the students the following:

Iron is attracted to a magnet, but it is not magnet by itself. Iron can become a magnet by rubbing it against a permanent magnet.

The iron nails will all point to the north because of the magnetic field of the earth itself.

This amazing property allowed sailors to tell which direction they were travelling when they could not see land.

The compass was invented by the Chinese; it was used in feng shui and divination. Use of the compass for navigation became common at a later date.

Additional Information If Needed: Iron and Magnetism

The Iron Age began about 5000 years ago.

Iron is the fourth most abundant element in the earth’s crust.

Most “iron” encountered in everyday life is actually an alloy consisting primarily of iron.

Carbon is one of the most common alloying elements. It is what makes steels hard. The other transition metals are also commonly used.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 31

Magnetism Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

Iron is the cheapest, most abundant, most useful, and most important of all the metals.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 32

Corrosion Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

Corrosion Demonstration

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

The Corrosion Demonstration shows that while iron and its alloys have many desirable properties, they are not perfect.

•

Pieces of steel wool are placed in two different cups, one with water, and one with a mild acid. After a time to allow the reaction to occur, the samples are examined for changes.

Potassium ferrocyanide is used to highlight the corrosion.

• The students will test 2 pieces of steel wool; the demonstrator will test 2 pieces.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

• 12 pieces of cleaned steel wool (2 on each table)

•

6 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups marked “water” (1 on each table)

• 6 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups marked “acid” (1 on each table)

•

6 plastic stirrers (1 on each table)

• 30 ml of 6 M HCl (5 ml for each table)

•

45 ml potassium ferrocyanide solution* (in plastic vial)

*For details on preparation of the ferrocyanide solution, see page 32.

• tap water

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

•

2 pieces of cleaned steel wool

• 1 clear, 4 oz. plastic cup marked “water”

•

1 clear, 4 oz. plastic cup marked “acid”

• 1 plastic stirrer

•

5 ml of 6 M HCl

• 7.5 ml. potassium ferrocyanide solution (in plastic vial)

• tap water

• plastic spoon

• disposable pipet

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 33

Corrosion Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

Corrosion Demonstration Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Remove and separate 14 pieces of steel wool from bag marked “Steel Wool” in demonstrator’s kit.

Place two each on the students’ tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Remove 14 clear, 4 oz plastic cups from demonstrators kit.

Mark 7 “water” and 7 “acid”.

Place one each on the students’ tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Place 5 ml (1 tsp) of the 6 M HCl in each of the 7 cups marked “acid”.

Add tap water to the cups marked “acid” until they are half filled.

Half fill the 7 cups marked “water” with tap water.

Fill the disposable pipet to the bottom of the bulb with the potassium ferrocyanide solution.

Dispense it to one of the 14 cups.

Add one pipet full of potassium ferricyanide solution to each of the other 13 cups.

Stir each of the 14 cups gently with the plastic spoon or plastic stirrers.

Place two cups on each of the student tables and the demonstrator’s table.

REMEMBER - 2% MURIATIC ACID IS 0.5 M HCl.

DO NOT LET STUDENTS PLAY WITH THE ACID.

Note: In case of a spill, wipe it up immediately with paper towels and clean with wet paper towels.

Corrosion Demonstration

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

When Iron Age man left his bright shiny iron tools out in the rain, he noticed that they were no longer shiny. This unfortunate truth hasn’t changed with time.

In fact they didn’t even look like metal anymore. They looked more like the rocks, although they now had the shape of the tools.

Iron Age man wondered if the gods of the rock were claiming his new tools.

Although we no longer look to rock gods to explain what happened to that Iron Age man, modern man still fights the same process.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 34

Now let’s look at that process.

Corrosion Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 35

Corrosion Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

Perform the Corrosion Demonstration Simultaneously With the Students

Part I – Starting the Corrosion

Do the following:

Pick up one of the wads of steel wool and the plastic cup marked “water”.

Have the students find their steel wool and plastic cup.

Drop the steel wool into the plastic cup. Use the plastic stirrer to get most of the air bubles off of the steel wool.

Have the students repeat your actions.

Pick up your other wad of steel wool and the plastic cup marked “acid”.

Have the students do the same.

Drop the steel wool into the plastic cup and watch the bubbles as before.

Have the students repeat your actions.

Tell the students that this will take some time to finish reacting.

Put both your plastic cups to the side for safe keeping. Have the students do the same.

Note: The corrosion will take 5 - 10 minutes to occur. Don’t forget to return to this before the program is complete.

Part II – Observing the Results

Do the following:

Put both of your cups back to the center of the table.

Have the students put both their cups in the center of their tables so they can all see.

Tell the students to carefully compare the steel wool in both cups, noting any differences in color.

Ask them what differences they see.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 36

Corrosion Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

Corrosion Demonstration Conclusion

Tell the students the following:

The blue color appears as the result of a reaction with a chemical that you added to the water and acid to make the corrosion easier to see.

Although the rock gods of Iron Age man are not causing this change, the iron is slowly turning back into one form of a rock.

This is the same thing that happens to the cars and bridges throughout Cleveland and the

Midwest.

Do you know what we usually call the product of the reaction? (Answer: rust)

We are observing a corrosion reaction where the iron combines with oxygen to form iron oxides, commonly known as rust.

We see corrosion in the cup with the acid, but in time, we would see it in a cup with just water. By adding a small amount of acid, we make the reaction go faster.

This is also the same type of reaction we looked at earlier with the different metals.

When we stop to look at why something like corrosion occurs and what can be done to prevent it, we are using the scientific method.

We have jumped all the way to the early 1500’s when the scientific method was first being used to answer these types of questions.

The tremendous progress in technology since the 1500’s is largely due to the use of the scientific method

Additional Information If Needed: Corrosion Demonstration Technical

Background

• The ferrocyanide ion {Fe(CN)

6

4-

Blue, Fe

4

[Fe(CN)

6

]

3

.

} combines with the iron ions in solution to form Prussian

• In addition to aiding the redox reaction with iron and water, the acid also helps to dissolve the

Fe

2

O

3

product, making the iron ions available for the reaction with the ferricyanide.

• Corrosion prevention and replacement of corroded parts costs an estimated $100 billion each year in the U.S. alone.

• The potassium ferrocyanide solution is made by dissolving 1 _ tsp. K

3

Fe(CN)

6

in 2.5 L water.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 37

Cleaning Silver Easily

Demonstrator’s Guide

Cleaning Silver Easily

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

With this demonstration, we reverse a corrosion reaction to produce nice shiny metal again.

• A piece of tarnished silver is placed on aluminum foil with some electrolyte. After a few minutes, the silver is clean.

• The students will clean 1 piece of silver; the demonstrator will clean 1 piece.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

• 6 pieces of tarnished silver (about 1 cm X 0.5 cm, 0.005” thick, tarnished with sulfur)

(1 on each table)

• 6 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups marked “silver” (1 on each table)

•

6 pieces of aluminum foil (1” X 1”, kitchen grade) (1 on each table)

• table salt

• tap water

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

•

1 piece of tarnished silver (about 1 cm X 0.5 cm, 0.005” thick, tarnished with sulfur)

• 1 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups marked “silver”

•

1 piece of aluminum foil (1” X 1”, kitchen grade)

• table salt

• tap water

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 38

Cleaning Silver Easily

Demonstrator’s Guide

Cleaning Silver Easily Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Remove the 7 pieces of silver from demonstrator’s kit.

Place one each on the students’ tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Remove 7 clear, 4 oz plastic cups from demonstrators kit.

Mark them “silver”.

Place one each on the students’ tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Place aabout 1/4 tsp. of table salt in each of the student’s cups.

Add about 2 TBS tap water to all 7 cups.

Remove the 7 pieces of aluminum foil from bag marked “Silver” in the demonstrator’s kit.

Place one each on the students’ tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Cleaning Silver Easily

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

Just like the shiny tools, the jewelry and fine objects made of silver also turned dark with time.

You might have seen this same thing happen at home to silverware, silver plates, or jewelry.

The way to get rid of this has traditionally been to rub the metal until the dark disappears and the metal is shiny again.

Since we are here in the 1500’s we can take advantage of the knowledge gained by using the scientific method in studying metals.

Now we are going to show an easy way to restore silver to being shiny. Instead of elbow grease, we will use the wisdom gained throughout time by the study of chemistry.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 39

Cleaning Silver Easily

Demonstrator’s Guide

Perform the Cleaning Silver Easily Demonstration Simultaneously With the Students

Part I – Starting to Clean the Silver

Do the following:

Pick up the plastic cup marked “silver” and the piece of aluminum foil.

Have the students find their aluminum foil and plastic cup.

Press the aluminum foil into the cup until the foil covers the bottom of the cup.

Have the students repeat your actions.

Add a about 1/4 tsp. of salt to the water.

Tell the students that you already added salt to their solutions.

Pick up the piece of silver and have the students pick up their silver.

Tell the students to carefully look at the appearance of the silver, noting the color.

Drop the silver into the cup and have the students do the same.

Tell the students that it will take some time for the silver to become clean.

Put your cup to the side for safe keeping and have the students do the same.

Note: The cleaning will take 5 - 10 minutes to occur. Don’t forget to return to this before the program is complete.

Part II – Observing the Results

Do the following:

Put your cup back to the center of the table.

Have the students put their cups in the center of their tables so they can all see.

Remove the piece of silver from your cup.

Tell the students to carefully remove the silver from their cups.

Tell them to carefully observe the color of the silver and compare it to what it looked like originally.

Ask them what differences they see.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 40

Cleaning Silver Easily

Demonstrator’s Guide

Cleaning Silver Easily Demonstration Conclusion

Tell the students the following:

Aluminum is a very reactive metal. Silver is not very reactive.

You took advantage of this difference to reverse the corrosion that made the silver turn black.

This returns the silver color.

The aluminum reacted with the black stuff on the silver. This left the silver metal.

The silver was not reactive enough to fight the aluminum and keep the black color.

Additional Information If Needed: Cleaning Silver Easily Demonstration Technical

Background

•

Silver tarnishes by reacting with sulfur compounds naturally present in the atmosphere, either as SO

2

, H

2

S or mercaptans (organic analogs of H

2

S), producing black Ag should not use silver utensils around eggs, which are rich in mercaptans.

2

S. This is why you

• The reaction between the Ag

2

S and aluminum is a redox reaction. The aluminum is oxidized, the Ag

2

S is reduced to metallic silver and sulfide ion. You might even be able to detect the aroma of H

2

S above the solution as the sulfide ion reacts with water in an acid/base reaction.

•

The table salt and water are necessary to form an electrolyte for this reaction to occur. To complete the electrochemical cell, the silver must be in physical contact with the aluminum.

•

In principle this technique will completely restore tarnished silver, even in fine crevices, without any loss of material. Repeated rubbing will eventually remove many of the raised details of a design while leaving the crevices dark.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 41

Forming Copper from Aluminum

Demonstrator’s Guide

Forming Copper from Aluminum

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

This experiment expands on the Cleaning Silver Easily demonstration to show a general practice of metal extraction from its ores; in other words, getting metal directly from a rock.

•

A few pieces of aluminum foil are placed into a vial containing a copper sulfate solution. The aluminum is oxidized, reducing the copper ions in solution to a pile of copper metal on the bottom of the vial.

• The students will use one sample; the demonstrator will use one sample.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

•

12 g copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate crystals with table salt

• 36 small squares of aluminum foil (kitchen grade) (3 on each table)

•

6 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups marked “copper”(1 on each table)

• 6 plastic vials

• tap water

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

• 2 g copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate crystals with table salt

•

6 small pieces of aluminum foil (kitchen grade)

• 1 clear, 4 oz. plastic cup marked “copper”

•

1 plastic vial

• tap water

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 42

Forming Copper from Aluminum

Demonstrator’s Guide

Forming Copper from Aluminum Experiment Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Remove the bag marked “Copper” containing copper sulfate and salt from demonstrator’s kit.

Remove the 7 plastic vials from the demonstrator’s kit.

Mix the copper sulfate and salt within the bag.

Place approximately equal amounts of the copper sulfate and salt in each of the seven plastic vials.

Place one of the plastic vials on each of the student tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Remove the bag marked “Copper” containing 42 small pieces of aluminum foil from the demonstrator’s kit.

Place six each on the student tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Remove 7 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups from the demonstrator’s kit and mark them "copper".

Place one on each of the student tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Put about 1 oz. of tap water in each of the cups (about _ filled).

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 43

Forming Copper from Aluminum

Demonstrator’s Guide

Forming Copper from Aluminum Experiment

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

As the need for metals increased, so did the number of ways developed to obtain them.

The same type of reaction that enabled the aluminum to clean the silver can be used to extract metals from their ores.

In this experiment, we will separate copper from one of its ores.

Perform the Forming Copper from Aluminum Experiment

Part I – Dissolving the copper sulfate

Do the following:

Pick up the vial of copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate and the cup of water marked “copper”.

Have the students find their own vials and cups.

Open your vial and pour the water into the vial. Recap the vial.

Have the students repeat your actions and recap their vials.

Tell the students that the first step to obtain metal from its ore is to put it into solution.

Have the students shake their vials vigorously.

Do the same with your vial.

Tell the students that it will take a little time for the water to dissolve the ore.

Note: It will take about a minute or two to dissolve the copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate.

Keep shaking the vial to speed dissolution.

REMEMBER - COPPER(II) SULFATE IS TOXIC.

DO NOT LET STUDENTS SPILL THE SOLUTION.

Note: If there is a spill, clean it up with paper towels.

The U.S. recommended Daily Allowance for copper (as Cu 2+ ) is 4 mg. To exceed that, the students would need to ingest 0.5 ml of this solution.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 44

Forming Copper from Aluminum

Demonstrator’s Guide

Part II - Electroless Plating of Copper from Solution

Do the following:

Pick up your vial of copper(II) sulfate solution.

Have the students do the same.

Pick up the small pieces of aluminum foil and have the student pick up theirs.

Open your vial and drop the aluminum pieces into it.

Show the students the reaction occurring and warn them of the temperature rise of the vial.

Have the students repeat your action.

Forming Copper from Aluminum Conclusions

Tell the students the following:

The solid accumulating on the bottom of the vial is copper metal. It looks different from a penny because it is many little tiny balls joined together in filaments or threads.

Normally you see metal as very large sheets or chunks.

This difference in the way the copper has been formed causes the different appearance.

If we removed the solid from the vial, melted it, and then cooled it, it would look as shiny as a new penny.

This is exactly what is done with metals made in this fashion.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 45

A Fruitless Battery (and Optional - Fruit Battery)

A Fruitless Battery

Demonstrator’s Guide

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

We show the differences of reactivities between two metals one more time. This time we use the difference to produce electricity.

•

A galvanized nail and a copper wire are placed into a solution of copper(II) sulfate (or a piece of fruit). The nail and copper wire are connected to a low power LED. The LED lights up showing a battery was made.

• Each student table will make a battery; the demonstrator will make one battery.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

• 6 LED set-ups* (1 on each table)

(*Each set-up consists of an LED with a galvanized roofing nail and a 2” piece of 12 gauge copper wire soldered in place.)

•

6 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups marked “battery” with copper(II) sulfate solution (1 on each table)

• Optional - 6 pieces of fruit (keep on demonstrator’s table until ready to use)

• paper towels

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

•

1 LED set-up

• 1 clear, 4 oz. plastic cup marked “battery” with copper(II) sulfate solution

•

Optional - 1 piece of fruit

• kitchen knife

• paper towels

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 46

A Fruitless Battery

Demonstrator’s Guide

A Fruitless Battery Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Remove the 7 LED set-ups (with galvanized nails and copper wire attached) from demonstrators kit.

Remove 7 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups from the demonstrator’s kit and mark them "Battery".

Remove the bag marked “Battery” containing copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate from demonstrator’s kit.

Place approximately equal amounts of the copper (II) sulfate in each of the seven cups marked

“Battery”.

Put about 2 oz. of tap water in each of the cups (about _ filled).

Place one each on the students’ tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Optional - Remove the fruit from the demonstrator’s kit.

If you have not already done so, cut the fruit into 7 pieces. (NOTE: Try the fruit battery at home first to make sure that the piece of fruit you pick will work . Plums, peaches, and melons work well. Citrus fruits are temperamental.)

Keep all the fruit on the demonstrator’s table.

A Fruitless Battery

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

Two hundred years ago, the rage in the scientific community was the new force of electricity.

Benjamin Franklin even became famous because he flew a kite in the rain looking for it.

An Italian named Volta discovered in 1800 that if you put two different metals in a bit of salt water, you can produce electricity.

He used his electricity to touch frog legs during dissection. The legs twitched as if they were alive. This simple demonstration of the electrical nature of nerves was used to create the legend of Frankenstein’s monster.

One hundred years ago, a company here in Cleveland started making the first dry cell batteries. That company became Eveready Battery, the makers of Energizer brand batteries.

Let’s see how two different metals can make a battery.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 47

A Fruitless Battery

Demonstrator’s Guide

Make A Fruitless Battery Simultaneously With the Students

Do the following:

Pick up your plastic cup marked “battery”.

Pick up your galvanized nail/copper wire/LED set-up.

Have the students collect their materials.

Stick the nail and the copper wire into the blue solution of copper(II) sulfate in the cup. Make sure that the wire does not touch the nail inside the solution.

Show the students that the LED is now lit.

Tell the students to stick their nails and wire into their solutions. Make sure that the copper wire and nail inside the solution do not touch.

Ask the students what they saw.

Ask them if they now have a battery.

Optional - Instead of, or in addition to the copper (II) sulfate solution, stick the nail and wire into a piece of fruit, making sure the nail and wire are not touching one another.

A Fruitless Battery Demonstration Conclusion

Tell the students the following:

The two different metals used were zinc from the galvanized nail and copper from the wire.

You took advantage of the different reactivities of metals to accomplish this.

Ask them if they think that they could change the results by using different types of solutions.

(As an option, you might want to have the different student tables use different types of fruit.)

Ask them if they remember which metal (zinc or copper ) they discovered was more reactive in the second experiment.

We have almost completed our journey back to the future. We’re somewhere in the 1800’s.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 48

A Fruitless Battery

Demonstrator’s Guide

Additional Information If Needed: A Fruitless/Fruit Battery Demonstration

Technical Background

• The fruit acts as the electrolyte and the source of copper ions.

•

The battery operates as the zinc on the galvanized nail is oxidized to Zn 2+ . The natural ions in the fruit move between the nail and the wire (cations move toward the copper, anions move toward the nail). At the copper wire, Cu 2+ ions from the solution are reduced to copper metal.

Electrons are carried through the LED from the nail toward the copper wire.

•

The nature of the solution does not have a major impact on the battery. The better the solution is able to conduct ions, the more current can flow. The more copper ions in the solution, the longer the battery can last.

• Since the solution does not have major impact on the battery, it is possible to replace the copper(II) sulfate solution with a piece of fruit. However, most fruit are not as conductive as the solution. This prevents the flow of a large enough current to light the LED.

•

Since the voltage of the battery depends on the types of metals used, rather than the solution, the voltage will not change, if a different solution is used. Using copper and zinc, the voltage of the battery will always be within a few millivolts of 1.1 V.

• Zinc is the more reactive metal, so it is oxidized. Copper is the less reactive metals so it is reduced.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 49

Electroplating Copper

Demonstrator’s Guide

Electroplating Demonstration

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

With this demonstration we take what we just learned to produce pure, reduced metal

(copper).

•

A brass fastener is placed in a cup of copper(II) sulfate solution and attached to a battery. The other end of the battery is connected to a copper wire and placed in the same cup. Copper plates onto the brass fastener.

• The students will plate 1 brass fastener; the demonstrator will plate 1 brass fastener.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

• 6 pieces of copper wire ( about 3” long, 12 gauge) (1 on each table)

•

6 brass fasteners (1 on each table)

• 6 red wires (22 gauge, 6” long) (1 on each table)

•

6 black wires (22 gauge, 6” long) (1 on each table)

• 6 AA size batteries (1 on each table)

•

6 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups

• 6 g of copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate

• tap water

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

•

1 piece of copper wire ( about 3” long, 12 gauge)

• 1 brass fastener

•

1 red wire (22 gauge, 6” long)

• 1 black wire (22 gauge, 6” long)

•

1 AA size battery

• 1 clear, 4 oz. plastic cup

•

1 g of copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate

• tap water

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 50

Electroplating Copper

Demonstrator’s Guide

Electroplating Demonstration Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Remove the 7 brass fasteners from demonstrator’s kit.

Place one each on the students’ tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Remove 7 clear, 4 oz. plastic cups from demonstrators kit.

Mark them “electricity”.

Remove the plastic bag marked “Hall” containing copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate from the demonstrator’s kit.

Evenly distribute the copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate among the 7 plastic cups.

Half fill each of the cups with water.

Place one plastic cup each on the students’ tables and the demonstrator’s table.

Electroplating Demonstration

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

From the time of its discovery, aluminum was a precious metal. It was much more expensive than silver. Napoleon III had bragged that he did not use silverware on his table. As Emperor of France he used aluminumware to eat.

Now lets jump to the year 1886.

A student at nearby Oberlin College is about to change the price of aluminum.

During the summer, Charles Martin Hall was trying to use electricity to extract pure aluminum from its ore, bauxite. He was able to discover a very inexpensive way to create aluminum.

At about the same time, a French chemist, Heroult was working on the same thing. He devised the same process that Hall did. Apparently, Napoleon III’s use of aluminumware impressed him.

Ever since, the Hall-Heroult process has been used to produce aluminum.

We cannot produce aluminum in the library. We don’t have enough equipment.

However, we can use the same type of process to produce copper. This copper will look more familiar than the copper we produced earlier.

In fact we will start with a solution made from the same “rocks” we used earlier.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 51

Electroplating Copper

Demonstrator’s Guide

Perform the Electroplating Demonstration Simultaneously With the Students

Do the following:

Pick up the plastic cup marked “electricity”, the brass fastener, and the copper wire.

Have the students find their plastic cup marked "electricity", brass fastener, and copper wire.

Have the students carefully observe the appearance of both the brass fastener and the copper wire.

REMEMBER - COPPER(II) SULFATE IS TOXIC.

DO NOT LET STUDENTS SPILL THE SOLUTION.

Note: If there is a spill, clean it up with paper towels.

The U.S. recommended Daily Allowance for copper (as Cu 2+ ) is 4 mg. To exceed that, the students would need to ingest 0.5 ml of this solution.

Pick up the AA battery and the red and black wires.

Have the students repeat your actions.

Clip the alligator clip of the red wire to one end of the copper wire.

Clip the alligator clip of the black wire to the round end of the brass fastener.

Connect the positive side of the battery (it has the raised bump) to the free end of the red wire.

Connect the negative side of the battery (it has the indented dimple) to the free end of the black wire.

Use one hand to hold both wires in place.

Tell the students to repeat your actions, being careful not to let the brass fastener touch the copper wire.

Now carefully place both the brass fastener and copper wire into the copper(II) sulfate solution in the plastic cup.

Have the students repeat your action, again being careful not to let the copper wire touch the brass fastener.

Wait approximately 2 minutes before continuing.

Pull the brass fastener and copper wire out of the solution and have the students do the same.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 52

Electroplating Copper

Demonstrator’s Guide

Electroplating Demonstration Conclusion

Do the following:

Ask the students to look at the ends of both the copper wire and the brass fastener that were in the copper(II) sulfate solution.

Ask them if there were any changes to either the brass fastener or the copper wire.

Ask them if they think that they produced copper metal from the solution.

Tell the students the following:

The different metals inside the battery produced electricity because of their different reactivities.

This electricity was then used to reverse a corrosion reaction and produce metal from a rock.

The same basic process is used to make thousands of tons of aluminum each year.

With Hall’s success, we’ve pretty much returned to our own time. We have just one more step.

Additional Information If Needed: Electroplating Demonstration Technical

Background

• The battery is powered by the oxidation of zinc metal at the negative pole and the reduction of manganese (IV) oxide to manganese (III) oxide at the positive pole. This same reaction powers Energizer, Duracell, Eveready, and Rayovac, in fact all “dry” cells.

•

The Hall-Herault process uses a molten salt of AlCl

Al

2

O

3

and cryolite (Na

3

AlF

6

) to dissolve the

3

from the bauxite. The temperature used for this process is 1300 ° C. We obviously can’t use this temperature in the libraries.

•

The modern process uses a mixture of sodium, aluminum, and calcium fluorides instead of the natural ore cryolite.

•

Copper ions from the solution are reduced on the brass fastener. Simultaneously, copper is oxidized from the wire and goes into solution. This process would not be an economical means of obtaining copper.

• Not all metals will work as well as the brass fastener as a site to plate copper. Since copper is such a non-reactive metal, most metals will react spontaneously when placed in a copper(II) solution much as the aluminum did earlier, being oxidized as copper ions are reduced to the metal. The brass fasteners we use are an alloy of copper and zinc that is less reactive than copper and so will not alloy copper to plate without the flow of electricity.

•

The Hall-Heroult process reduced the price of aluminum from $545/lb in 1852 to $0.30/lb by about 1900.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 53

Electroplating Copper

Demonstrator’s Guide

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 54

A Metal that Remembers Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

A Metal that Remembers Demonstration

Background and Set-Up Information For Demonstrators

Experiment Purpose & General Methodology

•

This demonstration takes our history tour to the present and beyond with one of the exotic new metal alloys being developed today.

•

A piece of wire formed in the outline of a clover is bent. When the wire is put into hot water, the wire returns to the shape of a clover.

•

The demonstrator will work with 1 piece of wire, allowing several students to try to bend it.

Materials For This Experiment - Students

•

None: this experiment is done by the demonstrator alone.

Materials For This Experiment - Demonstrators

•

1 piece of “memory metal” shaped like a clover

• 1 clear, 8 oz. plastic cup

•

1 insulated sytrofoam cup

• boiling hot water

•

1 plastic stirrer

A Metal that Remembers Demonstration Pre-Work Set-Up

Do the following:

Remove the “memory metal”, 8 oz. plastic cup, stirrer, and insulated styrofoam cup from the demonstrator’s kit.

Boil some water just prior to the program’s start and store it in the styrofoam cup.

Note: If you brought boiling hot water from home in an insulated container, keep it in that until needed.

DO NOT USE THE SAME WATER USED FOR THE MELTING METAL DEMONSTRATION.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 55

A Metal that Remembers Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

A Metal that Remembers Demonstration

Introduce the Experiment

Tell the students the following:

While mankind has been working with metals for 10,000 years, there is still more work to be done.

The last major breakthrough in obtaining metals from rocks was Hall’s discovery over 100 years ago.

Work now focuses on developing new alloys, or mixtures of metals that have very specific and unique properties.

We will now investigate such a property of a new alloy. This alloy remembers its past, even better than an elephant does.

Perform the A Metal that Remembers Demonstration in front of the Students

Do the following:

Pour the boiling hot water from the insulated styrofoam cup into the clear plastic cup.

Ask a student to come up to the front.

Show the metal wire shaped like a clover to all the students.

Have the student in the front bend the wire in several different ways, but don’t allow the student to knot it.

Thank the student for helping and have them take their seat again.

Show the now-bent metal wire to all the students.

Ask the students if they think that the clover pattern is now lost.

Tell them that you wonder if it really is and drop the wire into the cup of hot water.

Use the plastic stirrer to remove the wire from the cup, being careful not to burn yourself.

Show the metal wire to all the students, it is now back in the shape of a clover.

You may repeat this several times, as time permits. Perhaps ask one person from each table to try their hand at bending the wire.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 56

A Metal that Remembers Demonstration

Demonstrator’s Guide

A Metal that Remembers Demonstration Conclusion

Tell the students the following:

This particular metal is made by a company in Mansfield, Ohio.

It can be used in any application that needs a metal to resume its shape after being bent.

It can also be used for safety devices, much like the fusible alloy at the beginning of the program.

The metal is made in a particular shape that keeps a valve open. The metal can then be bent to close the valve. When the temperature gets high enough, the metal “remembers” its original shape and opens the valve.

Additional Information If Needed: A Metal that Remembers Demonstration

Technical Background

•

See literature that comes with the “memory metal”.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 57

Closing Session

Demonstrator’s Guide

Closing Session

Close Demonstration

On September 17, 1997, the American Chemical Society declared Oberlin

College a National Historical Chemical Landmark in honor of the work that

Charles Martin Hall did there while he was a student. Attending the dedication ceremony was Bernard Guest from France, the grandson of Heroult.

We’ve succeeded in getting back to the future from our little trip through time.

We’ve traveled from the present to the Stone Age and back again to the present.

Our keys to this journey have been metals.

We did not build a time machine from metals. We used the chemistry of metals to tell us the history of mankind and civilization’s use of metals.

I hope we’ve been able to show you that heavy metal is more than rock, it’s history.

By the way, why are metals called heavy? It’s because most will sink when placed in water or oil.

National Chemistry Week 1997 - Cleveland Section 58

Appendix

Demonstrator’s Guide

Contents of Demonstrator’s Kit

Malleability of Metals

1 bag marked “Al Mall” containing 7 pieces of aluminum foil (2” X 2” X 0.001”)

1 bag marked “Cu Mall” containing 7 pieces of copper foil (2” X 2” X 0.001”)

13 new pennies

Melting of a Metal boiling hot water

1 insulated styrofoam cup

1 clear, 8 oz. plastic cup

1 plastic stirrer

1 piece of Onion’s Fusible Alloy

Reactivity of Metals

7 pieces of solid copper wire (12 gauge, 1” long”)

7 magnesium strips

7 galvanized roofing nails

21 clear 4 oz. plastic cups