Chapter 20 The Properties of Acids and Bases

advertisement

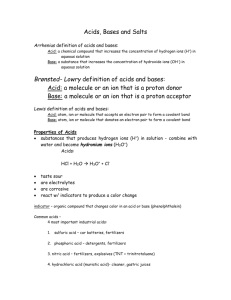

Chapter 20 The Properties of Acids and Bases Acids and bases play a key role in many areas of chemistry. Often they are part of equilibrium systems, so now that you understand equilibrium better we can begin to discuss the intricacies of acid-base systems Again, I and going to skip around a little bit in the order I present things 20-1 Acids and Bases Arrhenius Def Acids make H+ also taste sour Bases make OH- also taste bitter and make hands slippery Works only in aqueous solutions In reality H+ does not exist Actually H3O+ the hydronium ion Brønsted- Lowry Acids = Proton Donors Bases = Proton Acceptors Focus on proton-transfer reactions Works in non-aqueous solutions Will be focus for rest of chapter Lewis Theory acid - electron pair acceptor Electrophile base - electron pair donor Nucleophile Especially good in understanding organic reactions like NH3 +BF3 20-2 Water Pure neutral water has some hydronium and hydroxide ions 2 H2O W H3O+ + OHacts as both donor and acceptor Key Definition: Kw = [H3O+][OH-] = 1x10-14 X = [H3O+] = [OH-] 1x10-14 =X2 X=SQRT(1X10-14) X = 1x10-7 Neutral solution when [H3O+] = [OH-] Basic solution when [H3O+]< [OH-] or [OH-] >1x10-7 & H3O+ > 1x10-7 Acidic solution when [H3O+]> [OH-] or [OH-] <1x10-7 & H3O+ > 1x10-7 2 20-3 Strong Acids and Bases Key Definition: Strong acids are acids that undergo 100% dissociation in water Strong bases are bases that undergo 100% dissociation in water The common strong acids and bases are listed in table 20.1 YOU NEED TO MEMORIZE THESE COMPOUNDS Sample calculation What are the concentrations of H3O+, Cl- and OH- in .03M HCl 100% dissociation so [H3O+]= [Cl-] = .03M [OH-] comes from KW KW = 1x10-14 = [H3O+][OH-] 1x10-14 = .03[OH-] [OH-] = 1x10-14/.03 = 3.33x10-13 What are the concentrations of H3O+, Ca2+ and OH- in .03M Ca(OH)2 100 % dissociation so [OH-] = .03M Ca(OH)2 x 2 OH/1Ca(OH)2 = .06M [Ca2+] = .03M Ca(OH)2 x 1 Ca2+ /1Ca(OH)2 = .03M [H3O+] comes from KW KW = 1x10-14 = [H3O+][OH-] 1x10-14 = .06[H3O+] [H3O+] = 1x10-14/.06 = 1.67x10-13 Neutral Ions Now let’s look at the back reaction If HCl + H2O 6 Cl- + H3O+ go to 100% completion How much of a tendency does Cl- have to do the back reaction: To Cl- + H2O 6 HCl + OHZip- Zippo - Zilch-Nada So Cl is a neutral ion And so on for all the anions of the strong acids Similarly for Na+ So the cations of strong bases are also neutral The neutral ions are summarized in table 20.3 YOU NEED TO MEMORIZE THESE IONS 20-4 Carboxylic Acids Skip temporarily 3 20-5 pH and Acidity You will find that the [H+] and [OH-] concentrations are are important in many reactions. Even if [H+] and [OH-] are not products or reactants in a reaction, they often serve as catalysts. In addition, all living organisms carefully try to keep [H+] carefully regulated because small fluctuations in [H+] or [OH-] can easily kill a cell Generally the concentrations of [H+] and [OH-] in water range from 1M to 1x10-14 M. With such a broad range of concentrations it is convenient to switch to a logarithmic scale. This scale is attributed to Søren Sørenson. The p of pH is those to mean the ‘power’ or exponent of the hydrogen ion concentration Key Equation pH = -log[H3O+] = -log[H+] Example problems Just a page ago we calculated that .03M HCl had a [H+] of .03M What is the pH of this solution? pH = -log [H+] = -log(.03) = -(-1.52 =1.52 We also determined that a.03M Ca(OH)2 had an [H+] of 1.67x10-13 What is the pH of this solution? pH = -log [H+] = -log(1.67x10-13) = -(-12.778) =12.778 You can do the same thing with [OH-] Key Equation pOH = -log[OH-] Sample Problem Continuing with the [OH-] side of the previous problems, the .03M Ca(OH)2 had an [OH-] .06M pOH = -log(.06) = - (-1.222) 4 As we tackle the OH side of the .03M HCl solution I want to show you something In the original problem we had [H+] = .03M then we used KW = 1x10-14 = [H3O+][OH-] to find that [OH-] = 1x10-14/.03 = 3.33x10-13 so pOH = -log (3.33x10-13) = -(-12.48) = 12.48 Bu there is a shortcut Key Equation pH + pOH = 14 (I can derive this for you, but you probably don’t want to sit through the math) Continuing example we already said that the pH of this solution was 1.52 using 14 = 1.52 + pOH pOH = 14-1.52 = 12.48 and you get exactly the same number More on pH scale Earlier I said that Neutral solution when [H3O+] = [OH-] Basic solution when [H3O+]< [OH-] or [OH-] >1x10-7 & H3O+ > 1x10-7 Acidic solution when [H3O+]> [OH-] or [OH-] <1x10-7 & H3O+ > 1x10-7 Making the equivalent statements using the pH scale we have Neutral pH = pOH = 7 Basic solution is when pH >7 or pOH <7 Acidic solution is when pH <7 or pOH >7 Figure 20.2 pH of some common solutions Earlier I also said that “Generally the concentrations of [H+] and [OH-] in water range from 1M to 1x10-14 “ In pH scale this means that generally pH and pOH values lie between 1 and 14 Emphasis on generally, there are exceptions: Practice problem What is the pH and pOH of a 5M HCl solution [H+] = 5 ! Note >1! -log(5) = -.7 -.7 !! 14 = pH + pOH; pOH = 14.7! 5 One last trick problem I may throw at you What is the pH of 1x10-8 HCl? Well, that should be easy pH = -log(1x10-8) = - (-8) =8 But what is wrong with that answer? HCl is an acid, but you just got a basic pH! The problem is that you forgot about water. Water is furnishing 1x10-7 H+ so H+ = 1x10-8 from the HCl and 1x10-7 from the water for total of 1.1x10-7 pH = -log(1.1x10-7) = 6.96 an acid pH Adding the water contribution on top of your original acid or base is only necessary when the acid (or base) concentration is < or = 1x10-7. It is also a bit of a quick and dirty approximation, when you get to analytical I will show you the proper way to handle this problem. pH6 [H+] By now you know that I want you to be able to do calculations forward and backwards. So how do you calculate [H+] from pH? Example Calculation If an HNO3 solution has a pH of 4.83, what is the concentration of [HNO3]? pH = -log [H+] 4.53 = -log[H+] -4.53 = log [H+] How do you get rid of the log function? Do 10^ on both sides of the equation On the left side 10^-4.53 = 10-4.53 On the right side 10^log cancels out so 10-4.53 = [H+] = 2.95x10-5 Since HNO3 is a strong acid with 100% ionization [H+] = [HNO3] = 2.95x10-5 Summarizing into a single equation Key Equation [H+] = 10-pH 6 20-6 Weak Acids and Bases If strong acids and bases have 100% dissociation, what do you think happens with weak acids and bases? You got it, <100% dissociation I will define % dissociation or % ionization as: Key Equation % dissociation or ionization =[A-]/[total acid] x 100% = =[A-]/([HA]+[A-]) x 100% While my equation doesn’t look like the book equation, they are essentially the same. The book used [H+] in the numerator I uses [A-] but, since HAWH+ + Athey are the same number! In the denominator the book uses the term [HA]o and calls this the stoichiometric concentration. It represents the total you put in, so again we are equivalent. For a base the equivalent would be Key Equation % ionization = [BH+]/total base x100% = [BH+]/([B]+[BH+]) x100% Sample calculation If a .01M solution of an acid has a pH of 4.75, what is the % ionization of the acid? .1M would represent the total amount of acid we have in the solution if the pH is 4.75, [H+] = 10-4.75 = 1.78x10-5 if [H+]=[A-] then [A-]= 1.78x10-5 and % ionization = 1.78x10-5/.01 x 100% = 1.78% ionized If a base is 5% ionized when it has a concentration of 0.0004 M, what is the pH of the solution? 5% = [BH+]/([B]+[BH+]) x 100% .0004 = [B]+[BH+] 5% = [BH+]/.0004 x 100% .05 = [BH+]/.0004 [BH+]=2x10-5 [BH+] = [OH-] = 2x10-5, pOH = -log(2x10-5) = 4.70 pH = 14-4.70 = 9.30 7 20-7 Ka and Acid Strength So now you know that weak acids have <100% ionization, how can you tell how much ionization? How can you tell an acid with a 95% ionization from one with .005% ionization? Let’s look at the equilibrium If the acid dissociation equation is HA + H2O W H3O+ + AThen the equilibrium equation is: K =[H3O+][A-]/ [HA] or HAW H+ + A- or [H+][A-]/[HA] We give this acid ionization K as special symbol, Ka And, using the logic from the last chapter a larger K means the reaction goes more to the right, so Key Concept The larger the Ka the more a weak acid ionizes. Or the stronger the acid. Table 20.4 Ka and pKa of weak acids Clicker question Rank the acids, acetic acid HClO2, HIO3 from weakest to strongest acid Note this table also includes a value for pKa. What is a pKa Key Equation pKa = -log Ka pKa ‘s are handy for certain calculations that we will see in the next chapter Calculating the pH of a weak acid You know how to calculate the pH of a strong acid, it is easy because you can assume 100% ionization. How do you calculate the pH of a weak acid? Sample calculation What is the pH of a .006 M solution of acetic acid? We attack this problem just like any other equilibrium problem 1. Write the balanced reaction CH3COOH + H2O W CH3COO- + H3O+ I will shortcut this to HA W H+ + A2. Write the equilibrium expression that corresponds to the balanced reaction Ka = [H+][A-]/[HA] 8 3. list initial concentrations and start your ICE table HA WH+ + AInitial .006 0 0 4. Calculate Q to determine what direction(if any) the reaction will shift With 0 products we don’t need a Q, you know it will go to products 5. using a single variable(X), define change for each concentration needed to reach equilibrium using X. Here, since we want to calculate pH which comes from [H+] we make [H+]=X [A-] = X [HA] = -X 6. Substitute modified concentration terms into the ICE table and the equilibrium expression HA WH+ + AInitial .006 0 0 Change -X X X Eq .006-X X X Ka = X@X/(.006-X) Ka = 1.8x10-5 (from table 20.4) 1.8x10-5 = X@X/(.006-X) 7. Solve the equilibrium expression for the unknown There are two ways to solve this, long and short Start with the long (.006-X)1.8x10-5 =X2 1.08x10-7 -1.8x10-5X = X2 X2 + 1.8x10-5X -1.08x10-7 =0 Using the quadratic -b +/- sqrt(b2-4AC) / 2A -1.8x10-5 +/- sqrt(3.24x10-10 + 4.32x10-7) / 2 -1.8x10-5 +/- sqrt(4.323x10-7) / 2 -1.8x10-5 +/- 6.575x10-4 /2 Ignoring the - root (6.575x10-4 -1.8x10-5)/2 6.395x10-4/2 3.18x10-4 pH = -log(3.18x10-4) = 3.49 Now the short, quick and dirty If X si small, the reaction does not go far to the right so .006-X ~ .006 1.8x10-5 ~ X2/.006 X = sqrt(.006@1.8x10-5 ) = 3.29x10-4 ; pH = 3.48 9 A little off, but not too bad The quick and dirty method usually works if the Ka is 10-4 or less if you see a Ka of 10-3 or greater you should use the quadratic 20-8 Successive Approximation The Q&D answer we got above was a lot faster than the quadratic, but us was off a bit 3.28x10-4 - 3.18x10-4 = .10x10-4 .10x10-4/3.18x10-4 x 100% = ~3% error The method of successive approximation is a way to get closer to the real answer without the quadratic In the Q&D we did an approximation that .006-X ~ .006 But once we solved the equation and found that X = 3.28x10-4 we can improve our answer Out improved answer is that .006-3.28x10-4 =.005672 And not solve the problem with is better approximation 1.8x10-5 ~ X2/.005672 X = sqrt(.005672@1.8x10-5 ) = 3.29x10-4 ; pH = 3.48 X = 3.19x10-4 And now our answer is < 1% off. You can even set up a spread sheet to do this over and over. But most of the time a single iteration will be just fine for most weak acid problems Now that you know how to handle weak acids, and you have seen the table with lots of different weak acids it is time to look at the most common weak acid seen in organic chemistry the carboxylic acid 20-4 The carboxylic acid (out of order) The most common acid you see in organic chemistry is the carboxylic acid often represented with the atoms COOH The structure is shown above, where R represents H or any C containing group 10 Two of the acids you may be familiar with are acetic acid and formic acid. Acetic acid is the acid (and the smell) found in vinegar, Formic acid is the irritant found in and bites ( it was first isolated in 1600's by distilling ants!) The acidic proton on these structures is the H on the COOH group. If you think about it you might wonder why. After all H-O-H with OH bonds is not acidic, and alcohols C-O-H groups are not acidic either. Th answer lies is the fact that the anion that is formed when the proton leaves is stabilized by spreading out the negative charge over 2 atoms as shown below: Is is interesting that you can actually see this in x-ray structures. The C=O bond is 123 pm, the C-O-H bond is 136 pm and the C-O bond in then resonance stablized anion is 127 pm 20-9 KB and base strength Now let’s turn our attention to weak bases The generic base reaction is: B + H2O 6BH + OHSo in this case the OH- that you associate with something being basic is the product of the reaction of a base with water Notice in the reaction B the base was a proton acceptor which matches our Bronstead Lowry defintion 11 Or H H-N: + H-O-H H H 6 H-N-H H + OH- The pair of electrons are donated to water which agrees with the Lewis model of a base Again this is a equilibrium reaction with a K, but we usually use the symbol KB for the base ionization or base protonation constant. In a similar manner as the acids Key Concept The larger the KB, the more the reaction goes to the right, so the stronger the base Table 20.5 Key Equation pKB ‘s for -log(KB) Clicker question Rank the bases ammonia, aniline, and ethylamine from weakest to strongest base All of the weak bases found in this table are amines, or nitrogen containing organic molecules. The lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen that can either accept protons or donate electrons (depends on the definition of base you use) is what these bases all have in common Calculating the [H+] or pH due to a base follows the same kind of logic as calculation involving acids, you just have to add one more step Sample Calculation Let’s calculate the pH of a .04M ethylamine Again we attack this problem just like any other equilibrium problem 1. Write the balanced reaction CH3CH2NH2 + H2O W CH3CH2NH3 + OHI will shortcut this to B + H2O W BH+ + OH2. Write the equilibrium expression that corresponds to the balanced reaction KB =[BH+][OH-]/[B] 3. list initial concentrations and start your ICE table B H2O WBH+ + OHInitial .04 Constant 0 0 4. Calculate Q to determine what direction(if any) the reaction will shift With 0 products we don’t need a Q, you know it will go to products 5. using a single variable(X), define change for each concentration needed to 12 reach equilibrium using X. Here, since we want to calculate pH which can be calculated form pOH which comes from [OH-] we make [OH-]=X [OH-] = X = [BH+] [B] = -X 6. Substitute modified concentration terms into the ICE table and the equilibrium expression B H2O WBH+ + OHInitial .04 Const 0 0 Change -X X X Eq .04-X X X KB = X@X/(.04-X) KB = 4.5x10-4 (from table 20.5) 4.5x10-4 = X@X/(.04-X) 7. Solve the equilibrium expression for the unknown There are three ways to solve this, long and short, and successive approximation Let’s just do the successive approximation 1st approximation .04-X ~ X 4.5x10-4 =X2/.04 X = sqrt (4.5x10-4 @.04) x ~ .00424 ND 2 approximation .04 -X ~.04 - .00424 ~ .03576 4.5x10-4 =X2/.03576 X = sqrt (4.5x10-4 @.03576) x ~ .0040 But X = [OH-] and we want pH, so [OH-] =.004, pOH = -log(.004)= 2.40 pH = 14-2.40 = 11.60 20-10 Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs So far we have concentrated on the forward reaction HA + H2O 6 A- + H3O+ Or B + H2O 6 BH+ + OHBut now let’s look at the reverse reactions A- + H3O+ 6 HA + H2O Or BH+ + OH- 6 B + H2O Note that re reverse reactions are also acid base reactions A- + H3O+ 6 HA + H2O Or BH+ + OH- 6 B + H2O H Acceptor H Donor H donor H acceptor Acid Base Acid Base 13 Key Definition So the acid’s anion is a base in the reverse reaction - we call this a conjugate base and a base’s cation is an acid in the reverse reaction - we call this a conjugate acid Sample problems What are the conjugates bases of the following acids? HClO3, H2PO4-, and CH3NH3+ Acids are proton donators, so what ion do you have left after they have donated their proton - ClO3-, HPO42- and CH3NH2 What are the conjugate acids of the following bases? CH3NHCH3, HPO4-2 , FBases are proton acceptors so what do you have after you have accepted a proton? - CH3NH2CH3+, H2PO4-, HF So the conjugate form of the weak acids are bases, and will make the solution basic. Also the conjugate form of the weak bases are acids, and will make the solution acidic. Now a reminder. What is the conjugate form of HCl, and is it an acids or a base. Similarly, what is the conjugate form of NaOH, and will it make a solution acid or base? (The anions of strong acids are neutral, the cations of strong bases are neutral !) Kb’s of weak acids So now you know that the acetate anion, CH3COO- should be basic because it is a conjugate base. But how strong a base is it? Well consider CH3COOH + H2OW CH3COO- + H3O+, Ka = 1.75x10-5 For the reverse reaction CH3COO- + H3O+W CH3COOH + H2O H2O + H2O WH3O+ + OH- Reverse so K = 1/Ka Kw Now if we add the above two equations together, what do we do with the K’s? (Multiply them) The result is CH3COO- + H2O WCH3COOH + OH- and this is our base reaction for the acetate ion. 14 KB = Kw/KA = 1x10-14/1.75x10-5 = 5.71x10-10 Key Equation The Kb for the conjugate base of a weak acid = Kw/KA Similarly for bases The KA for the conjugate acid of a weak base = KW /KB Or, more simply, KAKB=KW Sample calculation What is the KA for ammonia (NH4+) KB for ammonia = 1.8x10-5 (table 20.5) KA = Kw/KB = 5.7x10-10 20-11 Salt solutions We started this chapter looking at strong acids and bases, then we worked on weak acids and bases, and just now we did the conjugate forms of the acids and bases. Now let’s put all these different pieces together into a compound called a salt. Back in chapter 10 you learned that a salt is the product of an acid base neutralization reaction, so let’s start there. What do you get when you neutralize an acid like HCl with NaOH? HCl + NaOH6 NaCl(aq) + H2O Early on in this chapter you learned that Na+ and Cl- were neutral ions, so the pH of the neutralized solution is indeed, neutral. Now what about CH3COOH and NaOH? CH3COOH + NaOH 6 CH3COONa(aq) + H2O But as an ionic compound CH3COONaW Na+ + CH3COONa+ neutral CH3COO-basic (C.B of a weak acid) How about HCl and NH3 6 NH4+ (acidic) and Cl- (neutral) So neutralization reactions can leave you neutral, or acidic or basic! What is a person to do? On top of that, sometimes I won’t even give you the neutralization reaction, I will just give you the salt, say NaHSO3. Are you up the proverbial creek without a paddle? Key Procedure: 1. Break each salts into its component anion and cation 2. Ignore the neutral cations and anions 3. Identify the acid/base properties of the remaining cation or anion 15 Table 20.7 is a nice table that summarizes the acid/base properties of many ions but you shouldn’t have to memorize this table, you should be able to use logic remember the cations of strong bases are neutral, so this means basically the first two column of the periodic table The anions of strong acids are neutral, and you shoul dknow your straong acids by now So you can ignore all of the above Looking at what remains The basic anions are the conjugate bases of weak acids The acidic cations are the conjugate acids of weak bases (and I think all have a N in them!) Table 20.7 does have a few that don’t fit above. Let’s examine them more closely 1. There are no basic cations! 2. Cations with >+2 charge tend to be acidic Last semester we talked about waters of hydration, that is waters that are bound to + cations When you have a highly charge cation, the cation actually grabs the water so strongly that it splits the water into OH- and H+. The OH- stays attached to the metal and the H+ is released Example: Al3+(aq) is actually [Al(H2O)6]3+ (aq) 6[Al(OH)(H2O)5]2+ (aq) + H+(aq) Added material NOT in your text Acid-Base properties of Oxides There is another class of compounds that have acid/base properties that we can identify fairly easily and that is the oxides. In nature you will find oxides of virtually every element. Oxides can be either acidic or basic. You now have enough chemistry behind you that you can begin to understand these properties and to predict them of unknown compounds. Let’s start with the acidic oxides. When a covalent oxide dissolves in water is will form an acidic solution. Examples: SO3 (g) + H2O(l)W H2SO4(aq) SO2 (g) + H2O(l)W H2SO3(aq) CO2 (g) + H2O(l)W H2CO3(aq) 2NO2 (g) + H2O(l)W HNO3(aq) + HNO2(aq) 16 On the other hand when ionic oxides dissolve in water we get basic solutions CaO(s) + H2O(l) W Ca(OH)2(aq) Na2O(s) + H2O(l) W 2NaOH(aq) K2O(s) + H2O(l) W 2KOH(aq) and these are called basic oxides In our covalent oxides the oxygen has a covalent bond to the cental atom and the H, and the bond between the central atom and the O is stronger than the bond between the O and the H so the H may be easily removed In the ionic compound there is no covalent bond between the metal and the O2anion. The oxide anion, in fact, has a high affinity for protons (a strong base) and will pull the off of water O2-(aq) + H2O(l) 6 2OH-(aq) Making most ionic oxides basic But hold it... In the lab you should have found that CrO3, a metal oxide had a pH of 2 or less. What gives? (In this compound you have Cr+6 We just talked about how metal ions with strong + Charge can be acids, here the acidity of the +6 metal ion has overpowered the basicity of the metal-oxide) Practice problems Maybe Clicker questions Identify the following compounds as acids or bases NaCl (N) CH3COOK (B) RbF (B) NH4NO3 (A) CaO (B) SO2 (A) CH3COONH4 (Trick question - N) 20-12 Polyprotic Acids Let’s talk a bit about H2SO4 and H3PO4 These are examples of polyproitic acids, acid that have more than one proton to give. There ae several polyprotic acids listed in table 20.9 of your text. If you look at the K’s of the polyprotics, you will see that form most of them the first K is relatively strong, but the second is much weaker. Can you figure out why? 17 After 1 proton remove you have an anion. It is harder to make the second proton leave a species that is already negatively charged to make it a doubly negatively charged species In analytical I will make you do calculations with these guys, and you might expect these calculations to be difficult because you have multiple states to deal with, But most of the time the second K is so small compared to the first that one can be ignored so the calculations -usually- aren’t to bad Amphoteric salts Some of the salts of some of the polyprotic acids can act as either an acid or a base Key Definition Species that can act as acid or bases are called amphoteric The salts of both H2CO3 and H3PO4 do this: Salt: NaHCO3 Ionizes to Na+ and HCO3-; Na+ is neutral and can be ignored HCO3 acting as acid HCO3- + H2O W CO32- + H+ HCO3- acting as base HCO3- + H2O W H2CO3 + OHThat is why a solution of NaHCO3 can be used in the lab to r=treat with acid or base burns