Date thesis is presented

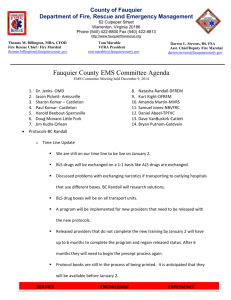

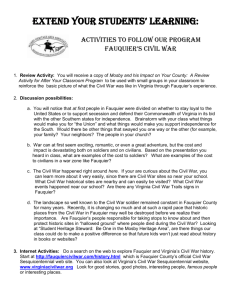

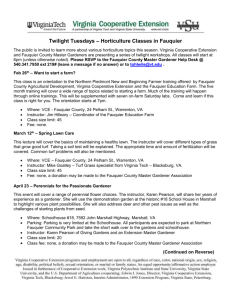

advertisement