Anti-Contraband Policy Measures: Evidence for Better Practice Summary Report

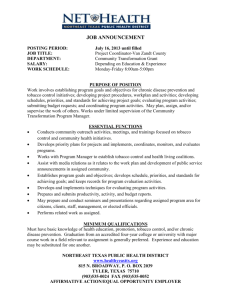

advertisement