COURT FILE NO.: COMMERCIAL LIST )

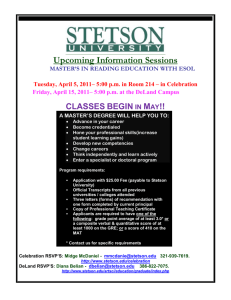

advertisement