Document 11530597

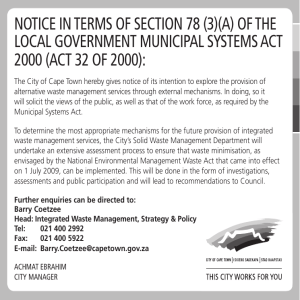

advertisement