Vanessa Fawbush for the degree of Master of Arts in... 2003. Title: Book of Changes.

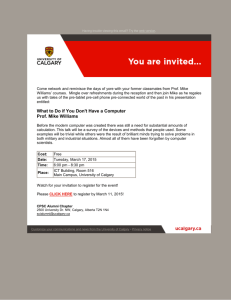

advertisement