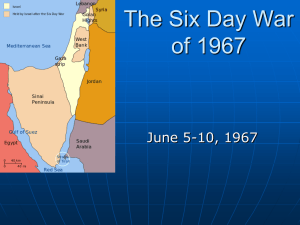

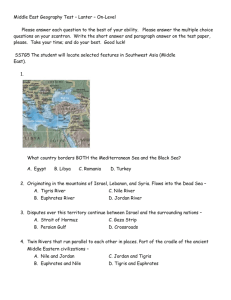

Hydrostrategic Decisionmaking and the Arab-Israeli Conflict

advertisement