Document 11508771

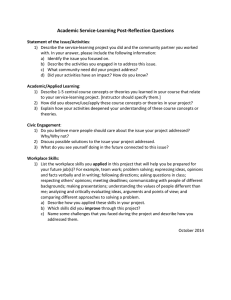

advertisement