Document 11508765

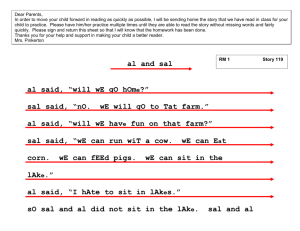

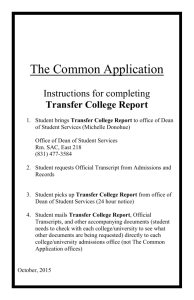

advertisement