From Uruguay to Doha: Agricultural Trade Negotiations at the World Trade Organization

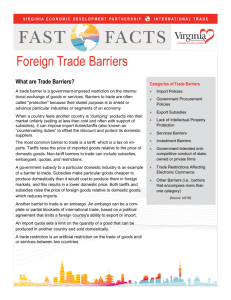

advertisement