Arabidopsis PHOSPHOTYROSYL PHOSPHATASE ACTIVATOR Is Essential for PROTEIN PHOSPHATASE

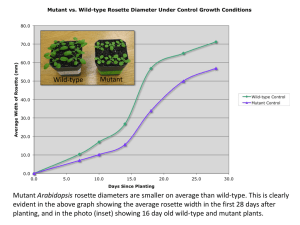

advertisement