Editorial: New Directions in Canine Behavior

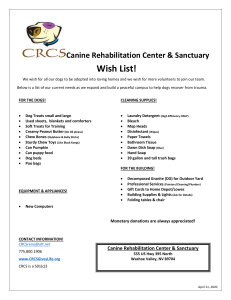

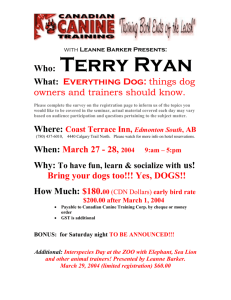

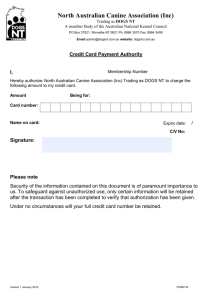

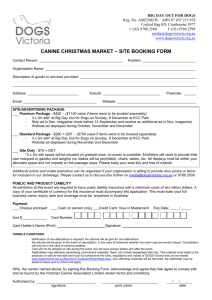

advertisement

Editorial: New Directions in Canine Behavior Udell, M. A. R. (2015). Editorial: New Directions in Canine Behavior. Behavioural Processes, 110, 1-2. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2014.12.001 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.12.001 Elsevier Accepted Manuscript http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Editorial/ Special Issue: New Directions in Canine Behavior Journal Citation: Udell, M. A. R. (2015). Editorial: New Directions in Canine Behavior. Behavioural Processes, 110, 1-­‐2. Editorial: New Directions in Canine Behavior (Pre-­‐publication version) Monique A. R. Udell Department of Animal & Rangeland Sciences, Oregon State University, 308 Withycombe Hall, 2901 SW Campus Way, Corvallis, OR 97331, United States. Telephone: 541-­‐737-­‐9154 Fax: (541) 737-­‐4174 Email: MoniqueUdell@gmail.com Editorial It has been just over five years since the first ‘Canine Special Issue’ was published in Behavioral Processes. As predicted in that issue, we have seen exponential growth in the number of researchers studying canine behavior, and consequently in the number of new publications arising from laboratories around the world. Pet domestic dogs have been the focus of much of this new research, however the number of studies investigating the behavior of wild canines, feral dogs, working dogs and shelter dogs has also grown significantly. Given the unique place pet and working dogs hold in many societies (Udell and Wynne, 2008), the billions of dollars such societies invest in dogs each year (APPA, 2014) and the important benefits and risks associated with human-­‐dog interactions world-­‐wide (e.g. McCardle et al., 2010; Overall and Love, 2001), this trend is likely to continue. Editorial/ Special Issue: New Directions in Canine Behavior Dogs have also become an important model for understanding social development, cognitive evolution and human ageing and disease, including cognitive and behavioral dysfunction (Head, 2013; Topál et al., 2009). However despite our 14,000+ year relationship with dogs (Nobis, 1979), cohabitation, and many years of fruitful scientific study, it is clearer than ever that we are just beginning to scratch the surface when it comes to understanding the rich behavior and cognition of the dogs we live with. We have even more ground to cover with non-­‐pet populations including working dogs, strays, and free-­‐roaming dogs – populations that represent the majority of the domestic dog species. Due to shrinking habitats, increased urbanization and human-­‐predator conflicts the study of non-­‐domesticated canids, including wolves, foxes and coyotes, has also become more critical than ever. This special issue, entitled New Directions in Canine Behavior, features an important collection of new research findings, approaches and ideas within the field of canine behavior and cognition. Many of these articles were invited based on presentations given as a part of the 2013 International Ethological Conference (IEC)-­‐Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour (ASAB) canine behavior symposium, held in Newcastle Gateshead, England, or the 2014 Society for the Promotion of Applied Research in Canine Science Conference (SPARCS) held in Newport, RI (see caninescience.info for more details). For example, two papers in this issue tackle the challenging topic of play behavior in dogs. While dogs are notorious for playful behavior even into adulthood, the origins and function of play behavior has been heavily debated (Bekoff and Byers, 1998). On pages ### of this issue, John Bradshaw and colleagues challenge Editorial/ Special Issue: New Directions in Canine Behavior the traditional single mechanism view of play behavior in dogs. Instead they suggest that ‘play’ may really be several different behavioral repertories with unique functions, motivations and evolutionary origins. An article by Kerri Norman, Sergio Pellis, Louise Barrett and Peter Henzi (Pages ####) also challenges a long held belief about play-­‐ specifically the notion that rollovers in dog-­‐dog play interactions are submissive in nature. Instead they suggest that dogs often roll over during play to gain a strategic advantage within an ongoing play sequence. As was true five years ago, canine scientists also continue to dig deeper into the origins of dogs’ responsiveness to human gestures. While the majority of research in this area has focused on dogs’ successes in this domain, two articles in the current issue demonstrate that dogs are not universally successful when it comes to reading human behavior. For example, an investigation of laboratory-­‐ reared dogs, by Lazarowski & Dorman (Pages ####), suggests that environment and experience are critical to a dog’s ability to follow human points. Another study by Yong & Ruffman (Pages ####) finds that dogs may not understand certain emotional expressions, such as human fear, as well as previously presumed. While dogs may indeed have an impressive capacity for responding to human behavior, a more refined understanding of the necessary conditions for this behavior to develop, and and limitations of these abilities, may provide a wealth of new information about the origins and development of canine social cognition. Such research may also provide knowledge about human-­‐canine interactions and environmental influences on cognition that may prove useful in applied settings. The origins and influence of canine-­‐human attachment has also gained Editorial/ Special Issue: New Directions in Canine Behavior increased attention in recent years. In this issue, Nathaniel Hall and colleagues (Pages ####) demonstrate that dogs are not alone in their ability to establish close bonds with human caretakers-­‐ human reared wolf pups show similar patterns of attachment suggesting a common origin for this predisposition. Kerepesi, Dóka, & Miklósi (Pages ####) investigate the influence of human presence (owner vs familiar vs unfamiliar individuals) on the behavior of dogs in a variety of situations. Their findings confirm the powerful role a bonded caretaker can play in the life of a dog-­‐ especially when the dog is afraid. These studies have raised new and important questions about what dogs and other canines may know about their human companions, as well as the aspects of human behavior they find salient or rewarding (see Feuerbacher et al., pages ####) and how this may influence their success in human controlled environments. Scientists are also turning more focus towards working dogs, an important group that has long been underrepresented in scientific studies on canine behavior and cognition. Mia Cobb and colleagues (pages ###) address current limitations of knowledge about the training and care of working dogs. With training success rates of less than 50% across industries, lack of understanding has come at considerable economic cost. Poor outcomes have also strained public perception, raising concerns about the long-­‐term prognosis for unsuccessful dogs. In this issue, working dog industries and canine scientists are challenged to seek evidence-­‐based answers that will lead to a new era of improved training, performance and welfare outcomes for dogs serving or assisting humans across a diverse range of settings. Importantly, prior behavioral research -­‐ primarily focused on pet dog populations -­‐may not Editorial/ Special Issue: New Directions in Canine Behavior accurately predict the behavior of this population. New research suggests that the specialized training that working dogs receive can lead to differences in social and problem solving behavior when compared to pets (see D’Aniello et al., Pages ####). Finally, promising new methods and approaches for studying canine behavior are being employed and evaluated. For example, an article by Gregory Berns and colleagues (Pages ####) features pet dogs trained to hold still in an MRI brain scanner while still awake, allowing scientists to monitor the dog’s brain activity as it is presented with a variety of stimuli-­‐ including the smells of familiar and unfamiliar individuals. Holly Miller and colleagues (pages #####) investigate the role of glucose and fructose in replenishing canine persistence after activities that require self-­‐control. Canine scientists have also begun to engage the general public in canine research and behavioral assessment. Citizen science projects (Hecht & Spicer Rice, pages ####), and methods that rely on surveys and other forms of community and owner generated data, are being used to gain an intimate understanding of dogs in their homes, as well as to study obscure or large populations that would be difficult to assess using traditional methods. The efficacy of non-­‐expert ratings is also being assessed as a possible resource-­‐saving measure for working dog evaluations; a task that currently consumes large amounts of expert time (Fratkin et al., pages ###). Of course, with new methodologies and techniques come new challenges. This issue addresses both the strengths and potential pitfalls associated with these new developments, while celebrating the exciting new possibilities ahead. Editorial/ Special Issue: New Directions in Canine Behavior In sum, this special issue features 15 articles that represent important New Directions in Canine Behavior, including new approaches, ideas, discoveries, interpretations and critiques that each contribute to the forward momentum of this growing field. These articles will no doubt serve as a catalyst for further advancement in canine research in the years ahead, along with the growing body of literature on canine behavior found in the pages of this journal and beyond. Acknowledgments I would first like to thank all of the authors that contributed their work to this special issue-­‐ it was a pleasure working with all of you. Thank you also to the many reviewers that provided timely and constructive feedback, the Behavioural Processes editorial and production staff for their continued assistance, and Johan Bolhuis for serving as the lead editor for several of the articles in this issue. Finally, a special thanks to Shamus O'Reilly and Clive Wynne, who provided me with the opportunity to serve as the Guest Editor for this special issue-­‐ and for the invaluable guidance and support along the way. References APPA, 2014. National Pet Owners Survey: Industry Statistics & Trends [WWW Document]. Am. Pet Prod. Assoc. URL http://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp (accessed 10.15.14). Bekoff, M., Byers, J.A., 1998. Animal Play: Evolutionary, Comparative and Ecological Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. Head, E., 2013. A canine model of human aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA -­‐ Mol. Basis Dis. 1832, 1384–1389. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.03.016 Editorial/ Special Issue: New Directions in Canine Behavior McCardle, P., Mccune, S., Griffin, J.A., Maholmes, V., Ph D. (Eds.), 2010. How Animals Affect Us: Examining the Influence of Human-­‐Animal Interaction on Child Development and Human Health, 1 edition. ed. Amer Psychological Assn, Washington, DC. Nobis, G., 1979. Der älteste Haushunde lebte vor 14000 Jahren. [The oldest domestic dog lived 14,000 years ago]. Umschau 79, 610. Overall, K.L., Love, M., 2001. Dog bites to humans—demography, epidemiology, injury, and risk. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 218, 1923–1934. doi:10.2460/javma.2001.218.1923 Topál, J., Miklósi, Á., Gácsi, M., Dóka, A., Pongrácz, P., Kubinyi, E., Virányi, Z., Csányi, V., 2009. Chapter 3 The Dog as a Model for Understanding Human Social Behavior, in: H. Jane Brockmann, T.J.R., Marc Naguib, Katherine E. Wynne-­‐ Edwards, John C. Mitani and Leigh W. Simmons (Ed.), Advances in the Study of Behavior. Academic Press, pp. 71–116. Udell, M.A.R., Wynne, C.D.L., 2008. A Review of Domestic Dogs’ (Canis Familiaris) Human-­‐Like Behaviors: Or Why Behavior Analysts Should Stop Worrying and Love Their Dogs. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 89, 247–261. doi:10.1901/jeab.2008.89-­‐ 247