Evaluation of reanalysis and satellite- based precipitation datasets in driving

advertisement

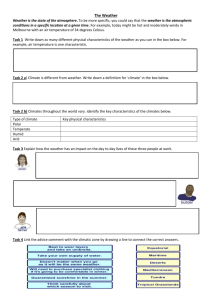

Evaluation of reanalysis and satellitebased precipitation datasets in driving hydrological models in a humid region of Southern China Hongliang Xu, Chong-Yu Xu, Nils Roar Sælthun, Bin Zhou & Youpeng Xu Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment ISSN 1436-3240 Volume 29 Number 8 Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003-2020 DOI 10.1007/s00477-014-1007-z 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by SpringerVerlag Berlin Heidelberg. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be selfarchived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 DOI 10.1007/s00477-014-1007-z ORIGINAL PAPER Evaluation of reanalysis and satellite-based precipitation datasets in driving hydrological models in a humid region of Southern China Hongliang Xu • Chong-Yu Xu • Nils Roar Sælthun Bin Zhou • Youpeng Xu • Published online: 31 December 2014 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 Abstract This paper compares the original and bias corrected global gridded precipitation datasets, tropical rainfall measuring mission (TRMM) and water and global change forcing data (WFD) with gauged precipitation and evaluates the usefulness of gridded precipitation datasets for hydrological simulations using the distributed soil and water assessment tool (SWAT) and lumped Xinanjiang model in Xiangjiang River basin, Southern China. The results show that the differences in areal mean rainfalls of original TRMM and WFD datasets and gauged dataset are in acceptable limits of less than 10 %, while larger differences exist in maximal 5-day rainfalls, dry spells and Fréchet distance. The bias correction methods are able to significantly improve the biases in the mean values of TRMM and WFD datasets. The nonlinear bias correction method gives good results in correcting the standard deviations of TRMM/ WFD data. The hydrological modelling results show that the WFD datasets perform relatively better than TRMM datasets even though the results are poor as compared with using gauged rainfall as input in daily step hydrological models. At monthly time step, both TRMM and WFD data produce acceptable model simulation results in terms of Nash– Sutcliffe efficiency (Ens [ 0.7 for original TRMM/WFD data and Ens [ 0.8 for linearly corrected TRMM/WFD data) and relative error (|RE| \ 10 %). H. Xu C.-Y. Xu (&) N. R. Sælthun Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, PO Box 1047, Blindern, 0316 Oslo, Norway e-mail: c.y.xu@geo.uio.no 1 Introduction H. Xu e-mail: xuhongliang.nju@gmail.com H. Xu Y. Xu Department of Land Resources and Tourism, Nanjing University, 22 Hankou Road Nanjing, Nanjing 210093, Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China C.-Y. Xu Department of Hydrology and Water Resources, Wuhan University, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China B. Zhou Department of Chemistry, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway B. Zhou Tianjin Academy of Environmental Sciences, 17 Fukang Road, Tianjin, People’s Republic of China Keywords Tropical rainfall measuring mission (TRMM) 3B42 Water and global change forcing data (WFD) Xinanjiang model Soil and water assessment tool (SWAT) Information about precipitation rates, amounts and distribution is indispensable for a wide range of applications including agronomy, hydrology, meteorology and climatology (Scheel et al. 2011). The spatial and temporal distribution of precipitation greatly influences land surface hydrological fluxes and states (Gottschalck et al. 2005). The precise measurement of precipitation at fine space and time resolution has been shown to improve our ability in simulating land surface hydrological processes and states (Faurès et al. 1995; Nykanen et al. 2001). Rain gauges provide rainfall measurements at individual points, but there is still a challenge in using gauged data to estimate rainfall at basin level with appropriate spatial and temporal scales (Sawunyama and Hughes 2008). With technological advancements, high resolution global topographical and hydrological data are currently 123 Author's personal copy 2004 available. There are many global rainfall databases (e.g. the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP), the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC), the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) precipitation database, the Climate Prediction Centre of NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Merged Analysis of Precipitation (CMAP), etc.), radar observations, and numerical weather precipitation models. However, their usefulness in driving hydrological models at basin scale is yet to be evaluated (Cheema and Bastiaanssen 2012; Parkes et al. 2013; Adjei et al. 2014). Much effort has been made in the correction of satellite products by using gauged rainfall (Kang and Merwade 2014). The mismatch between the rainfall estimates from satellite sensors and the gauges unavoidably leads to distrust in both datasets (Ciach et al. 2000; Grimes et al. 1999; Omotosho and Oluwafemi 2009; Nair et al. 2009). Some studies have compared the differences between the various precipitation datasets and rain gauge data as well as their impact on hydrological modeling (e.g. Abdella and Alfredsen 2010; Pan et al. 2010; Cheema and Bastiaanssen 2012; Fekete et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2012; Li et al. 2013). They have shown that global precipitation products can be used as a source of information but need calibration and validation due to the indirect nature of the radiation measurements. Comparing with gauged data, although these global precipitation datasets generally agree in their longterm temporal trends and large scale spatial pattern, remarkable differences at small time scale and at smaller spatial scale (basin, grid, etc.) can be observed (Adler et al. 2001; Costa and Foley 1998; Oki et al. 1999; Castro et al. 2014). Fekete et al. (2004) compared six monthly precipitation datasets to assess their uncertainties and associated impacts on the terrestrial water balance. The study demonstrated a need to improve precipitation estimates in arid and semi-arid areas, where slight changes in rainfall could result in significant changes in the runoff simulation due to the nonlinearity of the runoff-generation processes. Biemans et al. (2009) compared seven global gridded precipitation datasets at river basin scale in terms of annual mean and seasonal precipitation, which revealed that the representation of seasonality is similar for all the datasets but noted large uncertainties in the mean annual precipitation, especially in mountainous, arctic and small basins. Li et al. (2013) compared two global gridded precipitation datasets (Tropical rainfall measuring mission (TRMM) 3B42 (TRMM dataset contains a number of sub-datasets and 3B42 denotes one globally daily precipitation sub-dataset) and WATCH (WATer and global CHange) forcing data (WFD) and evaluated their performance in hydrological simulations of the WASMOD-D model over 22 basins in Southern Africa. The study showed that the two datasets had similar spatial variation patterns in the mean annual 123 Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 rainfall and temporal trends, while WFD data slightly outperformed the TRMM 3B42 data in the hydrological simulations over Southern Africa. Li et al. (2012) studied the difference of TRMM 3B42 rainfall with gauged precipitation data at different time scales and evaluated the usefulness of the TRMM 3B42 rainfall for hydrological processes simulation and water balance analysis using a distributed water flow model for lake catchment (WATLAC) in Xinjiang catchment in China. The study suggested that the TRMM 3B42 rainfall data were unsuitable for daily streamflow simulations but better performance can be achieved in monthly streamflow simulations. Rasmussen et al. (2013) investigated the range of the TRMM rainfall biases in storms over South America and indicated that the TRMM rainfall data significantly underestimate the storms with deep convective cores, while the bias is unrelated to their echo top height. Müller and Thompson (2013) adjusted the bias of the distributions of daily rainfall observed by the TRMM satellite through stochastic modeling in Nepal with a sparse gauge network and complex topography, and the results indicated that the bias adjusted satellite data through stochastic modeling outperformed the directly interpolated gauged rainfall. The study of Castro et al. (2014) showed that the tropical rainfall measuring mission multi-satellite precipitation analysis (TMPA) products for the rainfall are able to capture the mean spatial pattern for flat areas on a monthly basis; however, satellite estimates tend to miss precipitation that is enhanced by flow lifting over the mountains. Although some studies comparing global gridded precipitation datasets and their performance in driving hydrological models have been carried out, an integrated approach that (1) compares the differences of original and bias corrected gridded precipitation datasets with gauged precipitation data in terms of basic statistics, seasonal patterns as well as the spatial distributions, and (2) examines the performances of the original and bias corrected gridded precipitation datasets in driving both distributed and lumped hydrological models at different time and spatial resolutions has not been seen in the literature, which motivated the current study. This paper is therefore designed to: (1) compare and evaluate the temporal characteristic and the spatial distribution of the original and bias corrected TRMM 3B42 and WFD datasets with gauged precipitation data in a humid climate basin in southern China, and (2) evaluate the performance of the original and bias corrected TRMM 3B42 and WFD data and gauged precipitation in driving a distributed hydrological model (SWAT) and a lumped hydrological model (Xinanjiang model) in the simulation of daily and monthly streamflows in the catchment. This study contributes to the enhancement of understanding the difference between the TRMM/WFD and gauged rainfall and improves the knowledge regarding the utility of the Author's personal copy Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 raw and bias corrected TRMM 3B42 and WFD rainfall datasets in driving lumped and distributed hydrological models in varying time steps. The study significantly contributes to hydrology as there is a clear need for evaluating the skills and usefulness of new global precipitation datasets with different spatial and temporal resolutions as an alternative data source for hydrological studies especially in data scarce regions. 2005 runoff of Xiangjiang River basin is 910 mm. The mean annual temperature is about 17 °C, the annual mean relative humidity is about 75 % in summer and about 80 % in winter, and the mean annual potential evapotranspiration is about 1,000 mm. There are clear differences in runoff among different seasons with 50 % of the flooding events occurring in June and July. 2.2 Data 2 Study area and data 2.1 Study area The Xiangjiang River basin (Fig. 1) is located between 24°300 -29°300 N and 110°300 -114°E in the central-south China with a total area of 94,660 km2 and a total river length of 856 km. The basin is surrounded by mountains in its headwaters with plains in the downstream. The basin’s rolling terrain accelerates the rainfall convergence and the variation of runoff. It is heavily influenced by monsoon climate, which brings heavy rainfall from the south in summer. The mean annual precipitation reaches approximately 1,600 mm, of which 68 % occurs in the main rainy season from April to September. The mean annual depth of Three precipitation datasets were used in this study: (1) TRMM 3B42 dataset, which is a number of climate rainfall products produced from the passive microwave (TMI) and precipitation radar (PR) sensors on board the tropical rainfall measuring mission (TRMM) satellite launched in November of 1997. The TRMM project aims to provide small-scale variability of precipitation by frequent and closely spaced datasets. TRMM uses a combination of microwave and infrared sensors to improve accuracy, coverage and resolution of its precipitation estimates; however, the ability of TRMM to specify moderate and light precipitation over short time intervals is poor (Huffman et al. 2007; Li et al. 2013). The TRMM 3B42 dataset, covering from 1st January 1997 to 31st December 2008 in time and 50°S–50°N in space, is one of the TRMM rainfall Fig. 1 The Xiangjiang River basin in Southern China and the hydro-meteorological stations 123 Author's personal copy 2006 products which uses the TMI 2A12 rain estimates to adjust high temporal resolution (3-hourly or higher) IR rain rates over daily gridded 0.25 9 0.25° latitude/longitude boxes. It has been used to drive distributed hydrological models in large river basins as well as in flood modelling (Huffman et al. 2007, 2010) (in the following text, TRMM 3B42 is abbreviated as TRMM). (2) WFD dataset was developed by the WATCH project (Weedon et al. 2011) as input for large-scale land-surface and hydrological models. WFD dataset is named as reanalysis data in the literature which is weather observation data assimilated into global grids by a numerical atmospheric model. The WFD dataset, from 1st January 1958 to 31st December 2001, consists of meteorological variables needed to run hydrological models, including 2 m air temperature, dew point temperature and wind speed, 10 m air pressure and specific humidity, downward long wave and shortwave radiation, rainfall and snowfall rates (Uppala et al. 2005; Li et al. 2012). (3) The gauged precipitation dataset which consists of 181 rain gauges (Fig. 1) from 1st January 1963 to 31st December 2005 was provided by the Hydrology and Water Resources Bureau of Hunan Province, China. The meteorological data including daily maximum and minimum air temperature, precipitation, wind speed, solar radiation, average daily humidity and runoff used in this study have been quality controlled by the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System (http://cdc.cma.gov. cn). The spatial data for the watershed (i.e., elevation, land use map, and soils distribution map) were prepared as inputs to the SWAT Model. The DEM with 90 m resolution was downloaded from SRTM (The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission; http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/srtm/). The 1 km resolution soil dataset with respect to texture, depth and drainage attributes was supplied by the SinoTropia Project (Watershed EUTROphication management in China through system oriented process modeling of Pressures, Impacts and Abatement actions). The land use images which consist of five classes (forest, agriculture, grass, urban, and water) were interpreted from the Landsat satellite images (downed from http://www.landsat.org/) by using ENVI Image Analysis Software. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 5-day rainfall amount, maximum dry spell length, Nash– Sutcliffe model efficiency coefficient (Ens) and Root mean squared error (RMSE)) are assessed in the study. Meanwhile, the discrete Fréchet distance (Frechet 1906; Alt and Godau 1995) which takes into account the location and ordering of the points along the curves are used to measure the closeness of two time series (TRMM/WFD and gauged rainfall series) if stretching and compression in time is allowed, but temporal succession is to be preserved. Unlike similarity measures (e.g. RMSE) which average over a set of similarity values, and dynamic time warping which minimizes the sum of distances along the curves (data series) (Driemel and Har-Peled 2013), the Fréchet distance captures similarity under small non-affine distortions and for some of its variants also spatiotemporal similarity (Maheshwari et al. 2011). Statistical methods used in this paper to evaluate the TRMM/WFD and gauged rainfall datasets include: (1) Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) test for checking whether the three datasets have the same distribution pattern; (2) student’s t test and (3) F test for checking the equality of mean value and variance between the three datasets, respectively. A 5 % significance level was used for the tests (1)–(3). Meanwhile, the areal mean precipitation used in the analysis is computed by using Thiessen Polygons algorithm (Zquiza 1998) and the spatial patterns of the three datasets are interpolated on the catchment using Ordinary Kriging method (Cressie 1988). 3.2 Bias correction methods Due to the fact that satellite data and reanalysis data have biases and random errors which are caused by various factors like sampling frequency, nonuniform field-of-view of the sensors, and uncertainties in the rainfall retrieval algorithms, many algorithms have been developed for bias correction (e.g. Yang et al. 1999; Li et al. 2010; Piani et al. 2010; Dosio and Paruolo 2011; Kang and Merwade 2014). In this paper, two widely used bias correction algorithms were adopted to correct the biases of TRMM and WFD precipitation data. 3.2.1 Linear bias correction method 3 Methodology 3.1 Statistical analysis methods In order to evaluate and compare the consistency and differences between the TRMM/WFD and gauged rainfall datasets, several basic statistical indices (i.e. annual areal mean rainfall, annual areal rainfall in wet/dry season, relative error (RE), Standard deviation (STDE), maximum 123 The linear bias correction method (Teutschbein and Seibert 2012) is simple and widely used, in which TRMM/WFD daily precipitation amounts, P, are transformed into P* such as P* = aP, using a scaling parameter, a ¼ O=P, where O and P are monthly mean gauged and TRMM/ WFD precipitation respectively. The monthly scaling factor is applied to each uncorrected daily TRMM/WFD data of that month to generate the corrected daily time series. Author's personal copy Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 2007 3.2.2 Nonlinear bias correction method Leander and Buishand (2007) developed a nonlinear bias correction algorithm to correct the precipitation P in the following form: P ¼ aPb ð1Þ where P* and P are the corrected and the original TRMM/ WFD precipitation data, respectively. The parameters a and b are obtained for each grid point of the considered domain on a monthly basis by using daily data iteratively with a root finding algorithm (Brent 1973): bðx; iÞ: CVðP bðx;iÞ Þ ¼ CVðPobs Þ aðx; iÞ: aðx; iÞPbðx;iÞ ¼ Pobs ð2Þ ð3Þ where x is the grid point to be corrected, i represents the month, the overbar alludes to the monthly average, and CV() is the coefficient of variation of the variables simulated at x in i by the TRMM/WFD (P) and of the observed variables (Pobs). of land management practices on the hydrology, sediment, and contaminant transport in agricultural watersheds under varying soils, land use, and management conditions (Arnold et al. 1998). SWAT is based on the concept of Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs), which are portions of a subbasin that possess unique land use, management, and soil attributes. The runoff from each HRU is calculated separately based on weather, soil properties, topography, and vegetation and land management and then summed to determine the total loading from the subbasin. The SWAT Model is based on the water balance equation (Neitsch et al. 2002): SWt ¼ SW0 þ t X ðRday Qsurf Ea Wseep Qgw Þ ð4Þ i¼1 where SWt is the final soil water content, SW0 is the initial soil water content on day i, t is the time (days), Rday is the amount of precipitation on day i, Qsurf is the amount of surface runoff on day i, Ea is the amount of evapotranspiration on day i, Wseep is the amount of water entering the vadose zone from the soil profile on day i, and Qgw is the amount of return flow on day i. 3.3 Hydrological models Xinanjiang Model is by far the most widely used hydrological model in China (Zhao et al. 1995) which was developed in 1973 and the English version was first published in 1980 (Zhao et al. 1980). Its main feature is the concept that runoff is not produced until the soil moisture content of the aeration zone reaches field capacity, and thereafter runoff equals the rainfall excess without further loss. The inputs to the model are daily areal precipitation, the measured daily pan evaporation and observed discharge for calibration. The outputs are the modelled outlet discharge from the whole basin, the estimated actual evapotranspiration from the whole basin, which is the sum of the evapotranspiration from the upper soil layer, the lower soil layer, and the deepest layer (Zhao 1992). Xinanjiang model has been applied successfully since it was published over very large areas including all of the agricultural, pastoral and forested lands of China except the loess. The model is mainly used for hydrological forecasting (Yao et al. 2009), and the use of the model has also spread to other fields of application such as water resources estimation, design flood and field drainage, water project programming, hydrological impact of climate change and water quality accounting, etc. (Hu et al. 2005; Ren et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2009; Yao et al. 2009; Bao et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2012). The US National Weather Service River Forecast System has also reported its good performance in the arid Bird Creek watershed in the United States (Singh 1995). The SWAT (Soil and Water Assessment Tool) Model is a distributed-parameter model designed to predict the effects 4 Results and discussion The results of the study are presented in the following order: (i) Comparison of original TRMM and WED data with gauged precipitation data, (ii) comparison of bias corrected TRMM and WED data with gauged precipitation data, (iii) evaluation of daily and monthly model simulation results using original TRMM and WED data and gauged precipitation data as inputs, and (iv) evaluation of model simulation results using bias corrected TRMM and WED data and gauged precipitation data as inputs. 4.1 Comparison of TRMM, WFD and gauged precipitation datasets Precipitation is the immediate source of water for the land surface hydrological budget, and its uncertainty will strongly impact the model calibration results (Li et al. 2012). The comparison between the Gauged, TRMM and WFD precipitation datasets was conducted in four steps: First, several statistical indices of the original TRMM and WFD (named as TRMMO and WFDO from now on) datasets and gauged precipitation data in the common period of 1997–2001 were analyzed; second, the intensity distribution and relative contribution of each rainfall class to the total amount of rainfall are evaluated; third, seasonal variation and correlations between TRMMO, WFDO and gauged rainfalls are quantified, and finally, spatial patterns of TRMMO, WFDO and gauged rainfalls were compared. 123 Author's personal copy 123 WFDO * Gauged TRMMO * Gauged Fréchet distance 35.3 Gauged 3 Root mean squared error (mm/day) TRMMO * Gauged WFDO * Gauged 0.49 Ens TRMMO * Gauged 0.36 6.1 5.5 TRMMO 205.7 Gauged 7.7 WFDO 7.4 TRMMO 8.7 WFDO * Gauged Gauged 124.7 TRMMO 16 WFDO 29 -4.4 % Max. dry spell (day) Max. 5-day rainfall (mm/5 day) Standard deviation (mm) WFDO * Gauged TRMMO * Gauged -3.9 % 177.3/90.3 Gauged WFDO 171.6/84.2 175.8/81.5 TRMMO 1,535 1,543.6 1,605.8 WFDO TRMMO Gauged Areal mean rainfall in wet/dry season (mm/month) Annual areal mean rainfall (mm/year) Table 1 Comparison of statistical indices among TRMMO, WFDO and Gauged areal rainfall from 1997 to 2001 The results of basic statistical indices are shown in Table 1. As an important and useful index to reflect the accuracy of rainfall amount, the annual areal mean gauged rainfall calculated by Thiessen polygon interpolation method is 1,605.8 mm/year, and for TRMMO and WFDO data the values are 1,543.6 and 1,535 mm/year, respectively. The average monthly rainfalls are 177.3, 175.8 and 171.6 mm/month for gauged, TRMMO and WFDO data respectively in wet season, while the values are 90.3, 81.5 and 84.2 mm/month respectively in the dry season. The RE of annual areal mean rainfall shows that both TRMMO and WFDO datasets recorded slightly less rainfall than gauged data in the region. A comparison of STDE computed from the three datasets showed that the difference of STDE between WFDO and gauged rainfall is smaller than the difference between TRMMO and gauged rainfall. The differences in the extreme rainfall which is reflected by the maximum 5-day rainfall (Dankers and Hiederer 2008) show that TRMMO dataset recorded 65 % more rainfall than gauged data in storms while the WFDO data only recorded 4 % more rainfall than gauged data. Considering the maximum dry spell days, both TRMMO and WFDO datasets suggest more non-rainy days compared with the gauged data. The Ens (taking the gauged data as ‘‘Observed data’’ and TRMMO/WFDO data as ‘‘Simulated data’’) between gauged data and TRMMO data (denoted as EnsTG) and between gauged data and WFDO data (denoted as EnsW-G) showed that the values of EnsW-G are higher than the values of EnsT-G, and both are lower than 0.5 during the period 1997–2001. The values of RMSE also show that the WFDO dataset is better than TRMMO data in the region. However, the Fréchet distances computed between TRMMO/WFDO and gauged monthly areal mean rainfall are 35.3 and 80.5 respectively, which means that the TRMMO rainfall is more similar with the gauged rainfall than that of the WFDO rainfall in monthly level in terms of the Fréchet distance measure. This inconsistency of result as compared with other statistical indices mentioned above is probably due to the Fréchet distance easily leads to irrelevant results if the temporal interdependence of values is of importance, which is true in the case of rainfall graphs and hydrographs (Chouakria-Douzal and Nagabhushan 2006; Ehret and Zehe 2011). In summary, the above comparisons showed that in the study region the WFDO data agreed better with the gauged data than the TRMMO data in most of the statistical indexes. Similar conclusions are also found in the literature. Li et al. (2013) showed that WED data provide better results than TRMM data in driven a large scale hydrological model in Southern Africa. In another study carried Relative error of annual areal mean rainfall 4.1.1 Basic statistical indices of original TRMM, WFD and gauged rainfalls 80.5 Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 WFDO 130 2008 Author's personal copy Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 2009 out by Li et al. (2014), it is shown that WED data agreed better with observed precipitation data than TRMM data in India. 4.1.2 Intensity distribution of different rainfall classes of original TRMM, WFD data and gauged rainfalls Figure 2 shows the intensity distributions of the TRMMO, WFDO and gauged daily precipitation in different classes and their contributions to the total rainfall from 1997 to 2001. It is seen that non-rainy days have the largest occurrence for the WFDO data, occurring 34 % of the total days, but for the TRMMO and gauged data, the largest class is 0 \ rainfall \ 3 mm, occurring more than half of the total days. The second largest class for the WFDO, TRMMO and Gauged data are 0 \ rainfall \ 3 mm, nonrainy days and 3 \ rainfall \ 10 mm respectively, occurring about 20–30 % of the total days. It is obviously seen Fig. 2 Distribution of daily precipitation in different precipitation classes (bar graphs) and their relative contributions (lines) to the total precipitation from 1997 to 2001 that both TRMMO and WFDO data observed much more non-rainy days than gauged data, which is partly because of the poor ability of recording trace rainfall for the TRMM satellite and the data assimilation algorithm, observation system and observation data applied in producing reanalysis WFD dataset (Ebisuzaki and Kistler 2000; Bengtsson et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2005; Bengtsson et al. 2007). The statistics for TRMMO rainfall are however different from WFDO and gauged rainfall, with the dominant rainfall classes contributing to the total rainfall of TRMMO data being 10 \ rainfall \ 25 mm and 25 \ rainfall \ 50 mm, both accounting for about 30 % of the total rainfall, while the 10 \ rainfall \ 25 mm is the dominant class contributing more than 40 % of total rainfall for the WFDO and gauged data. The sum of the first two classes, i.e. non-rainy and small rain (0 \ rainfall \ 3 mm) classes, gives a similar high percentage (approximately 65 %) of total days for all the three datasets, but the contributions to the total 70 60 Percentage (%) 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 0-3 3-10 10-25 25-50 50-100 Range bins (mm) Occurence_TRMM₀ Contribuon_TRMM₀ Occurence_WFD₀ Contribuon_WFD₀ Occurence_Gauged Contribuon_Gauged 123 Author's personal copy 2010 Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 4.1.3 Seasonal variation and correlations between TRMMO, WFDO and gauged rainfalls Figure 3 shows a quantitative comparison of the spatial average of the mean monthly precipitation over Xiangjiang River basin from TRMMO, WFDO and gauged data during 1997–2001. The figure graphically demonstrates that WFDO data agree better with the gauged data than TRMMO data do in 9 months except March, May and July. It is seen that the monthly rainfall values of TRMMO data are lower than gauged rainfall in winter (December–February) and autumn (September–November), but in spring (March–May) and summer (June–August), the comparison of TRMMO and gauged rainfall varies irregularly. On the 300 TRMMₒ Precipitaon (mm/month) 250 WFDₒ Gauged 200 150 100 400 y = 1.0267x - 8.7564 R² = 0.9269 TRMMO precipitation (mm) 300 200 100 0 0 400 100 200 Gauged precipitation (mm) 300 400 300 400 y = 0.9864x - 4.0819 R² = 0.9561 300 WFDO precipitation (mm) rainfall amount are all below 10 % in the low rain class. The occurrences of the middle class rainfall (3 \ rainfall \ 50 mm) decrease progressively class by class for the three datasets, but with different contribution rates to the total rainfall. The highest rainfall class ([50 mm) occurs below 0.5 % of the total days and contributes 6.2, 2.1 and 3 % of the total rainfall for TRMMO, WFDO and gauged data respectively. The TRMM satellite obviously records more precipitation in high rainfall class than the rain gauges which is mainly because the heavy rainfall in the study area is dominated by the frontal rains and connective rains, and inside these heavy frontal rains and connective rains, rain rate is distributed heterogeneously in vertical and horizontal directions. Therefore, the complex distribution of rain in the clouds produces large error in rainfall volume detected by the Precipitation Radar on TRMM satellite (Zipser and Lutz 1994). It is important to note that the high rainfall ranges play a vital role in contributing to the total rainfall amount. This kind of information is essential because heavy rains cause the geographical slides and flash floods and hence threaten the economies and human life (Varikoden et al. 2010; Li et al. 2012). 200 100 0 0 100 200 Gauged precipitaon (mm) Fig. 4 Scatter plots of the correlation between monthly areal mean precipitation from TRMMO, WFDO and gauged data (1997–2001) other hand, the monthly rainfall values of WFDO data are always lower than Gauged rainfall except in August. Correlation of the three datasets is shown through the scatter plots of monthly areal TRMMO, WFDO rainfall against gauged rainfall in Fig. 4. It is seen that there are good linear relationships between the WFDO data and gauged data, with the highest determination coefficient (R2) of 0.96. The R2 value for the correlation between TRMMO data and gauged data is 0.93. From the comparison of the two scatter plots and the R2 values, slope and intercept of the regression lines, it is seen that the WFDO data reproduced the observed amount of monthly rainfall slightly better than the TRMMO data in the study region. 50 0 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Month Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fig. 3 Mean monthly precipitation in Xiangjiang River basin from TRMMO, WFDO and gauged data (1997–2001) 123 4.1.4 Spatial patterns of TRMMO, WFDO and gauged rainfalls Figure 5 shows the spatial distribution of relative error of precipitation (Fig. 5a–f) and Ens computed between gauged Author's personal copy Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 2011 Fig. 5 The spatial distribution of Relative error of precipitation and Ens between gauged and TRMMO/WFDO datasets (computed in the common period of 1997-2001): Relative error of precipitation between gauged and TRMMO datasets in a annual mean, b mean monthly rainfall in wet season, c mean monthly rainfall in dry season; Relative Error of precipitation between gauged and WFDO datasets in d annual mean, e mean monthly rainfall in wet season, f mean monthly rainfall in dry season; g is the Ens computed by gauged and TRMMO datasets and h is the Ens computed by gauged and WFDO datasets 123 Author's personal copy 2012 Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 and TRMMO/WFDO datasets (Fig. 5g, h) interpolated by using Ordinary Kriging method in the common period of 1997–2001. It is seen that the TRMMO data underestimate the annual rainfall in the whole basin while the RE is larger in western and southern parts of the basin than it is in central-north part of the basin (Fig. 5a). In wet season, the distribution of RE varies regularly from TRMMO data overestimating the rainfall in the north/west to underestimating the rainfall in the south/east (Fig. 5b). In dry season, the TRMMO data underestimate the rainfall in the whole basin and RE values increase gradually from north to south (Fig. 5c). The distribution of RE computed by WFDO data and gauged rainfall shows similar spatial variation pattern in annual mean rainfall (Fig. 5d) and mean monthly rainfall in wet season (Fig. 5e), and WFDO data vary from overestimating rainfall in the north to underestimating in the south gradually, while Fig. 5f shows that the WFDO data overall underestimate the mean monthly rainfall in dry season except a slight overestimation in the northern part of the basin. Figure 5g, h shows that the WFDO data match the gauged rainfall much better than the TRMMO data do. The WFDO data match the gauged rainfall best in the northwest of the basin with EnsW-G value reaching 0.4, and with the worst estimates in the north. The TRMMO data match the gauged rainfall poorly in the western and northern parts of the basin with the EnsT-G values below zero and the highest value of EnsT-G in eastern part of the basin is still lower than 0.3. The consistency test of the TRMMO and WFDO datasets in terms of their distribution patterns (K–S test), long-term mean values (t test) and variances (F test) is performed for the areal average values and for each grid cells at the significance level of 0.05. As for the areal average values, the t test shows the differences in mean annual and seasonal values of TRMMO and WFDO data with gauged data are insignificant at 5 % significant level. The differences in their spatial distribution patterns and the variances are significant at 5 % significant level. The results of consistency test for individual grid cells are summarised in Table 2, which shows that: (1) The Null Hypotheses that Table 2 The results of hypothesis test among TRMM, WFD and Gauged precipitation in Xiangjiang River Basin Total grid number = 36 TRMMO and gauged data belong to the same distribution and have same variance are not rejected in only four grids; whereas the Null Hypotheses that WFDO and gauged data belong to the same distribution and have same variance is therefore rejected in all grids. And (2) the student’s t test shows two thirds of the grids (24 grids) of TRMMO rainfall and one third of the grids (11 grids) of WFDO rainfall in the basin have the same mean values as gauged rainfall. 4.1.5 Comparison of bias corrected TRMM and WFD datasets with gauged data The areal mean precipitation is one of the decisive factors for the lumped hydrological models due to lumped models consider a watershed as a single unit for computations, and model inputs and watershed parameters are averaged over this unit. However, the spatial distribution of precipitation amounts is vital for the distributed hydrological models. Figure 6 shows the comparison of bias corrected TRMM/ WFD precipitation data using the linear and nonlinear correction methods (in the following part of the paper, the linear corrected TRMM/WFD data are abbreviated as TRMMLC/WFDLC and nonlinear corrected TRMM/WFD data are abbreviated as TRMMNLC/WFDNLC) with gauged rainfall for the individual grid as well as for the areal average. It is seen that: (1) The biases existed in the uncorrected annual mean rainfall of TRMM/WFD data disappeared after using linear/nonlinear bias correction algorithms both in grid and areal mean rainfall level. (2) In case of the original and bias corrected TRMM datasets, it is seen that the values of STDE (which were computed by the TRMMO in each grid and the areal mean TRMMO) are larger than the values of STDE of gauged rainfall in most grids and in areal mean level in the catchment. The values of Ens calculated between TRMMO and gauged rainfall in each grid are all smaller than 0.4 while the Ens calculated between areal mean TRMMO and areal mean gauged rainfall is 0.52. It is evidently seen in Fig. 6a that the nonlinear bias correction method removes the bias of the STDE both in grid and areal mean rainfall level, and the Hypothesis TRMMO versus Gauged (1997–2005) 4 WFDO versus Gauged (1963–2001) Kolmogorov–Smirnov test The same distribution Not the same distribution 32 36 Student’s t Test The same mean 24 11 Not the same mean 12 25 F Test The same variance 4 0 32 36 Not the same variance 123 Number of grids 0 Author's personal copy Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 (a) 40% 0.4 20% 0.2 0% 0 Annual Mean of Grid Standard Deviaon of Grid Annual Mean of Areal Mean Rainfall Standard Deviaon of Areal Mean Rainfall Ens of Grid Ens of Areal Mean Rainfall -20% -40% Error Variation -0.2 -0.4 Uncorrect 60% Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient 0.6 Linear Correct Nonlinear Correct (b) 40% 0.4 20% 0.2 0% 0 -20% -0.2 -40% -0.4 Uncorrect WFDNLC and areal mean gauged rainfall are observed in Fig. 6b. The worsening of Ens values in grid level of WFDNLC is mainly because the nonlinear bias correction algorithm can correct the water balance (relative error) well, but cannot correct the zero values in WFD precipitation when the gauged precipitation is not zero, since only the non-zero records are adjusted to achieve the solution of objective function in the correction period which could lead to considerable variation of nonzero rainfall values. 4.2 Evaluation of streamflow simulation using TRMM, WFD and gauged precipitation as inputs 0.6 Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient Error Variation 60% 2013 Linear Correct Nonlinear Correct Fig. 6 Comparison of error variation of uncorrected, linearly corrected and nonlinearly corrected TRMM/WFD precipitation with gauged precipitation: a TRMM * gauged, b WFD * gauged values of Ens computed between TRMMNLC and gauged rainfall improved in both grid and areal mean level. However, the linear bias correction method neither remove the bias of the STDE nor improve the values of Ens computed between TRMMLC and gauged rainfall in both grid and areal mean rainfall level obviously. (3) In case of the original and bias corrected WFD datasets, it is seen that the values of STDE (which were computed by the WFDO in each grid and the areal mean WFDO) are smaller than the values of STDE of gauged rainfall in most grids and in areal mean level in the catchment. It is seen in Fig. 6b that the nonlinear bias correction method removes the bias of the STDE in grid level, but the STDE computed by the areal mean WFDNLC is 15 % larger than the STDE computed by the areal mean gauged rainfall. However, comparing with the gauged rainfall, the linear bias correction method removes the bias of the STDE which was computed by the areal mean WFDLC but does not remove the bias of the STDE in grid level. Comparing the values of Ens computed between WFDO/WFDLC/WFDNLC and gauged rainfall in each grid, it is seen that the linear bias correction method improves the Ens values slightly at grid level while the nonlinear bias correction method does not improve the Ens values in most of the grids. Meanwhile, the worst Ens values which were calculated by the areal mean WFDLC/ The common period of the TRMM, WFD and gauged precipitation datasets 1997–2001 was taken for model calibration. In order to make best use of the available data which cover different record periods, the validation period for gauged and TRMM data was 2002–2005 and the period 1993–1996 was taken for validation of WFD data. The period 1st January 1997–31st May 1997 was taken as warming-up period during calibration. In the SWAT model, the catchment was delineated into 55 sub-basins and 555 HRUs (Hydrological Response Units) depending on elevation, soil types and land-use types. In model calibration, the Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient was taken as objective function, the Genetic Algorithm and SUFI2 (Sequential Uncertainty Fitting version 2) Algorithm provided by SWAT CUP were used for calibrating the Xinanjiang Model and SWAT Model respectively. All the 15 parameters of Xinanjiang Model and the 12 most sensitive parameters of SWAT Model (ranked by CN2, SOL_AWC, GWQMN, ESCO, GW_DELAY, ALPHA_BF, SOL_BD, SOL_K, REVAPMN, SLSUBBSN, SURLAG and GW_REVAP) were selected for calibrating the models (Table 3). The same initial values and range of parameters were applied in calibrating the different data based models. 4.2.1 Evaluation of the daily step simulated streamflow The evaluation of model simulation results at daily time step is performed on two aspects in this study and results are presented in the following three paragraphs in this section, i.e., statistical quality measures of Ens and RE, and graphical comparison of observed and model simulated daily discharges. Table 4 shows the Ens values and Relative Error (RE) for the Xinanjiang and SWAT Models’ simulation results. In case of Ens values, it is seen that: (1) The gauged precipitation data based hydrological models performed best while the performances of the TRMMO and WFDO precipitation based models were far from being satisfactory at daily time step. (2) The Ens values using the linearly corrected TRMM and WFD data as input improved from 0.62 123 Author's personal copy 2014 Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 Table 3 The calibrated parameters of Xinanjiang model and SWAT model Xinanjiang model Name Description Um Averaged soil moisture storage capacity of the upper layer (mm) Lm SWAT model Name Description Parameter range 10–60 ALPHA_BF Base flow recession factor (days) 0-1 Averaged soil moisture storage capacity of the lower layer (mm) 50-160 GW_DELAY Ground water delay (days) 0-15 Dm Averaged soil moisture storage capacity of the deep layer (mm) 100-180 GW_REVAP Ground water revaporation coefficient 0-0.5 B Exponential parameter with a single parabolic curve, which represents the non-uniformity of the spatial distribution of the soil moisture storage capacity over the catchment 0.3-0.7 GWQMN Threshold depth for ground water flow to occur (mm) 0-10 Im Percentage of impervious and saturated areas in the catchment Ratio of potential evapotranspiration to pan evaporation 0-0.1 SLSUBBSN Average slope length (m) 0-100 0.1-1.2 SOL_BD Moist bulk density (g/cm3) 0-25 Coefficient of the deep layer that depends on the proportion of the basin area covered by vegetation with deep roots Areal mean free water capacity of the surface soil layer, which represents the maximum possible deficit of free water storage (mm) 0.1-0.3 SOL_K Saturated hydraulic conductivity (mm/hour) 0-10 30-60 REVAPMN Threshold depth for revaporation to occur (mm) 0-100 Ex Exponent of the free water capacity curve influencing the development of the saturated area 1-2 ESCO Soil evaporation compensation factor 0-1 Kg Outflow coefficients of the free water storage to groundwater relationships 0.9-0.99 SOL_AWC Available water capacity (m/m) 0-1 Ki Outflow coefficients of the free water storage to interflow relationships 0.8-0.9 CN2 Curve number Cg Recession constants of the groundwater storage 0.3-0.7 SURLAG Surface runoff lag coefficient (days) Ci Recession constants of the lower interflow storage 0.3-0.7 Ke Parameter of the Muskingum method 0.1-4 Xe Parameter of the Muskingum method 0.1-4 K C Sm Parameter range and 0.79 to 0.65 and 0.81 in the Xinanjiang Model as compared to the Ens values using uncorrected data. The Ens values improved from 0.56 and 0.71 to 0.63 and 0.73 in SWAT Model respectively. However, the Ens values using nonlinear correction method show slightly worse results in case of WFDNLC data in both models. Specifically, the Ens values using the non-linearly corrected TRMM and WFD data as input changed from 0.62 and 0.79 to 0.67 and 0.76 in the Xinanjiang Model, and changed from 0.56 and 0.71 to 0.64 and 0.66 in SWAT Model respectively as compared to the Ens values using uncorrected data. (3) Similar conclusions can be drawn for the validation period. Both linear and nonlinear correction methods improved the simulation results in the validation period for both models in the case of TRMM data, while in the case of WFD data linear correction method improved model simulation results but opposite results were obtained for the nonlinear correction method. And (4) in summary, WFD data, both original and bias corrected, suggest better results than TRMM data in 123 -25–30 0-20 the calibration period at daily time step for both models; nonlinear correction method performs better model simulation results than linear correction method for both models in the case of TRMM data; as for WFD data, linear correction method provides better model simulation results than the nonlinear correction method for both models. In case of Relative Error values, it is seen from Table 4 that (1) comparing simulations with uncorrected data the values of RE produced by TRMMLC reduced in both models, and the values of RE produced by WFDLC reduced in Xinanjiang model and increased in SWAT model in the calibration period. In the validation period, the values of RE increased/decreased in the case of TRMMLC/WFDLC for Xinanjiang model, while opposite is true for SWAT model. (2) The RE values produced by TRMMNLC increased/ decreased in the case of Xinanjiang/SWAT models in both calibration and validation periods, while opposite is true in case of using WFDNLC data. Above comparison reveals that, combining both quality measures of Ens and RE, the Author's personal copy Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 2015 Table 4 Comparison of model performance in daily step simulation based on the input of TRMM, WFD and gauged precipitation Gauged TRMM Uncorrected Xinanjiang model SWAT model WFD Linear corrected Linear corrected 0.96 0.62 0.79 0.81 -1.8 % -5.9 % -3.6 % -9.6 % 1.8 % 0.8 % Validation period Ens Relative error 0.94 -3.9 % 0.85 5.1 % 0.72 16.5 % 0.78 16.6 % 0.75 -3.3 % Calibration period Ens 0.9 0.56 0.63 Relative error 1.3 % 7.5 % 5.2 % Validation period Ens 0.89 0.6 0.67 0.72 16 % 11.6 % Ens Relative error -0.7 % 20.4 % 0.67 Uncorrected Relative error Calibration period 0.65 Nonlinear corrected 0.64 -6.3 % 0.71 -1.2 % 0.74 -2.4 % Nonlinear corrected 0.76 1% 0.71 2.1 % 0.73 0.66 -1.7 % 11 % 0.68 0.72 0.62 -1 % 1.9 % -11.5 % Fig. 7 Comparison of the observed and simulated daily hydrographs at Xiangtan station: a TRMM based Xinanjiang model, b TRMM based SWAT model, c WFD based Xinanjiang model, d WFD based SWAT model WFD data is relatively better suited for the daily step hydrological simulation than the TRMM data in this study basin. For illustrative purpose, Fig. 7 shows the comparison of the observed and simulated daily stream flow hydrographs of year 2000 in the calibration period in Xiangtan gauge which are produced by the original and bias corrected TRMM and WFD rainfall datasets in Xinanjiang Model and SWAT Model respectively. It is seen that: (1) The WFDLC daily rainfall based Xinanjiang Model matches the observed discharge well, followed by the WFDO daily rainfall based Xinanjiang Model. Compared with the WFD data based hydrological models, TRMM data perform poorly in simulations. The simulated hydrographs show a tendency for the models to misestimate the extreme peak flows. This can be attributed to the low precision of original and mean monthly bias corrected TRMM and WFD rainfall data in matching the maximum rainfalls. And (2) 123 Author's personal copy 2016 Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 Table 5 Comparison of model performance in monthly step simulation based on the input of TRMM and WFD precipitation Gauged TRMM WFD Uncorrected Xinanjiang model SWAT model Ens Linear corrected Nonlinear corrected Uncorrected Linear corrected Nonlinear corrected Calibration period 0.98 0.76 0.81 0.82 0.92 0.94 Validation period 0.98 0.9 0.89 0.95 0.94 0.95 0.92 -2.8 % 0.95 -3.9 % 0.72 2.5 % 0.81 2.3 % 0.73 -0.4 % 0.85 -0.6 % 0.88 -0.3 % 0.74 0.94 0.83 0.88 0.85 0.9 0.92 0.81 9.6 % 4.4 % 1.8 % -1.1 % -0.1 % Relative error Ens Calibration period Validation period Relative error -1.9 % 0.89 1.3 % Fig. 8 Comparison of the relative error of mean monthly runoff simulation driven by original and bias corrected TRMM and WFD rainfall data in a TRMM datasets based Xinanjiang model, b TRMM datasets based SWAT model, c WFD datasets based Xinanjiang model and d WFD datasets based SWAT model the corrected and uncorrected TRMM/WFD data (except WFDNLC based SWAT Model) all show lower discharge than observed discharge in dry season while they show higher values than observed discharge in the wet season in both hydrological models. and the Ens values are 0.98, 0.98, 0.95 and 0.94 for the calibration and validation periods of the Xinanjiang and SWAT models respectively. The relative errors are all smaller than 3 %. As for the results of TRMM and WFD datasets, the following results are obtained: (1) the largest RE value is reduced from 9.6 % for the case of uncorrected TRMM data to 4.4 % for linearly corrected TRMM data. The RE values for all other bias corrected cases are smaller than 3 %. (2) The Ens values of WFDLC based Xinanjiang Model are the highest, achieving 0.94 and 0.95 in calibration period and validation period respectively. (3) The nonlinearly corrected datasets generally perform worse results than linearly corrected datasets with an exception of TRMM data for Xinanjiang model. And (4) it can be concluded that both 4.2.2 Evaluation of the monthly step simulated streamflow To demonstrate the suitability of the TRMM and WFD datasets in monthly step hydrological simulation, Table 5 shows the precision of the original and bias corrected TRMM and WFD precipitation data based models for monthly streamflow simulation. It is seen that the gauged data based models still gave the best model performances, 123 Author's personal copy Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 TRMM and WFD rainfall data can be used as model input for monthly flow simulation in the study region and again WFD data perform better than TRMM data. The seasonal biases of the simulated discharges using observed precipitation and original and bias corrected TRMM/WFD datasets are compared for both Xinanjiang and SWAT models (Fig. 8). It can be seen from the figure that: (1) In case of original and bias corrected TRMM data based Xinanjiang Model (Fig. 8a), the TRMMNLC data produce the best simulation results in general (all |RE| \ 10 % except in April). The TRMMLC based model misestimated the flow obviously (|RE| [ 10 %) in most of the months except January, May, June and September. (2) In case of original and bias corrected TRMM data based SWAT Model (Fig. 8b), compared with the TRMMO based model, TRMMLC data considerably improve the flow simulation in February, August, September, October and November. Meanwhile, the TRMMNLC data considerably improve the flow simulation in January, April, August, October, November and December. (3) In case of original and bias corrected WFD data based Xinanjiang Model (Fig. 8c), the WFDLC/WFDNLC data obviously produce larger error than the WFDO data in flow simulation in January-April and November and the WFDNLC data also considerably overestimate the flow in the model in September. However, in June–September (raining season), the WFDLC based model estimates the flow very well (|RE| \ 5 %). (4) In case of original and bias corrected WFD data based SWAT Model (Fig. 8d), the WFDO based SWAT model underestimates the streamflow obviously except in May and July. The WFDLC based model considerably improves the flow simulation compared with the WFDO data based model in most months (except May, July and November). Meanwhile, the RE values of flow produced by the WFDNLC based model improve in January, June, August–October and December obviously compared with the RE calculated by the WFDO data based model, but considerably worsen RE values can also be observed in March, may, July and November. In summary, above results reveal that the linearly corrected WFD rainfall data give the best prospect for monthly step streamflow simulation in both models. However, the nonlinearly corrected TRMM dataset has the potential to be a suitable data source for the data-poor or ungauged basins due to its real-time updating, particularly for the large-scale or meso-scale basins in remote locations. 2017 corrected TRMM and WFD rainfall for discharge simulation using lumped Xinanjiang Model and distributed SWAT Model in Xiangjiang River Basin, south China. The following conclusions can be drawn from the results of this study: (1) (2) (3) 5 Conclusions This paper compared the differences between TRMM and WFD rainfall datasets with gauged rainfall data at daily and monthly time steps and evaluated the accuracy of bias (4) The differences of the mean annual and seasonal areal precipitation calculated from the gauged precipitation and the two original global datasets (TRMMo and WFDo) are in general within the acceptable value of less than 10 %, and the linear correlation between the monthly gauged precipitation and TRMMo and WFDo data as reflected by the interception, slope and R2 are in general very good. However, the spatial differences as reflected by the results of K–S test and F test on each grid for distribution pattern and variance are found to be significant between the gauged and the two global datasets (TRMMo and WFDo) in most grids, while the student’s t test shows two thirds (one third) of the grids of TRMMO (WFDo) rainfall in the basin have the same mean values as gauged rainfall. The differences in maximum dry spell are significant between the two global datasets and the gauged rainfall, while the difference in maximum 5-day rainfall is significant between TRMMo and gauged values. The bias correction methods are able to remove the biases existed in the mean values of TRMMo and WFDo datasets. The nonlinear bias correction method gives good results in correcting the standard deviation values in TRMM/WFD data at grid level. The Ens values of TRMM data improved after nonlinear bias correction in most of the grids as well as in the areal mean rainfall. The linear bias correction method gives good results in correcting the standard deviation of areal mean WFD data. But the Ens values of WFD data do not improve in both grid and areal mean level after linear or nonlinear bias correction. The comparison of model simulation results using gauged precipitation and the two original global datasets (TRMMo and WFDo) as inputs to the two hydrological models reveals that at daily time step both TRMMo and WFDo produce much worse results than using observed precipitation data in terms of Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency Ens and relative error, RE. Both linearly and nonlinearly bias corrected TRMM and WED data do not significantly improve the model simulation results at daily time step. At monthly time step the modelling study shows that both TRMM and WFD data produce acceptable 123 Author's personal copy 2018 (5) Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 model simulation results in terms of both Nash– Sutcliffe efficiency (Ens [ 0.7 for original and nonlinear corrected TRMM/WFD data, Ens [ 0.8 for linear corrected TRMM/WFD data) and relative error (all |RE| \ 10 %). Linear correction method produces better simulation results than nonlinear correction method and the best results were found from Xinanjiang Model using linearly corrected WFD data without considering gauged data based models. In general, it can be said that the reanalysis WFD data matches the gauged precipitation better and produce slightly better model simulation results in the region than the TRMM data, and the lumped Xinanjiang model performs better than the distributed SWAT model at both monthly and daily time steps. However, it should be noted that: (1) (2) Several shortcomings still exist in using global datasets in hydrological simulations, as TRMM and WFD overestimate or underestimate the rainfall in different years and areas, and have a generic failure to detect the small and extreme rainfall which limit the precision of discharge simulation at daily time steps and in hydrological applications including drought and flood forecasting. These shortcomings in TRMM and WFD datasets indicate that further efforts of evaluating the satellite-based and reanalysis datasets need to be continued in more areas with different scales and climatic conditions and using hydrological models with different spatial–temporal resolutions. The spatial autocorrelation is not considered due to a dense network of rain gauge stations is available in this study to remedy the bias of TRMM and WFD datasets grid by grid. However, when the reanalysis/ satellite based datasets are used in the basins without such densely distributed rain gauges to interpolate grid rainfall, the Biased Sentinel Hospitals-Based Area Disease Estimation (B-SHADE) model which takes into account prior knowledge of geographic spatial autocorrelation and non-homogeneity of target domains, remedies the biased sample, and maximizes an objective function for best linear unbiased estimation (BLUE) of the regional mean (total) quantity (Wang et al. 2011) can be adopted as an alternative choice to correct the bias. Unlike the bias correction methods applied in the study that simply considers the statistical relationship between data series, the B-SHADE model considers coexistence of homogeneity and heterogeneity of the variant in land surface (Wang et al. 2009, 2010). 123 (3) Meanwhile, the B-SHADE model uses correlation between stations and selecting several observation stations of greatest correlation that can better reflect the reality (Xu et al. 2013). Furthermore, the newly released WATCH-ForcingData-ERA-Interim (http://www.eu-watch.org/data_ availability), a dataset produced post-WATCH using WFD methodology applied to ERA-Interim data, extends the meteorological forcing dataset into early twenty first century (1979–2012) and provides an alternative dataset for ungauged or sparsely gauged basins for hydrological analysis and modelling. The usefulness of this dataset will be evaluated in the on-going research. Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editor who helped us improving the quality of original manuscript. The authors would like to thank the SinoTropia Project (Watershed EUTROphication management in China through system oriented process modelling of Pressures, Impacts and Abatement actions) who provided the soil distribution map used in SWAT Model. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61301063). References Abdella Y, Alfredsen K (2010) Long-term evaluation of gaugeadjusted precipitation estimates from a radar in Norway. Hydrol Res 41(3–4):171–192 Adjei KA, Ren LL, Appiah-Adjei EK, Odai SN (2014) Application of satellite-derived rainfall for hydrological modelling in the datascarce Black Volta trans-boundary basin. Hydrol Res. doi:10. 2166/nh.2014.111 (in Press) Adler RF, Kidd C, Petty G, Morissey M, Goodman HM (2001) Intercomparison of global precipitation products: the third precipitation intercomparison project (Pip-3). Bull Am Meteorol Soc 82(7):1377–1396 Alt H, Godau M (1995) Computing the Fréchet distance between two polygonal curves. Int J Comput Geom Appl 5(01n02):75–91 Arnold JG, Srinivasan R, Muttiah RS, Williams JR (1998) Large area hydrologic modeling and assessment part I: model development1. JAWRA J Am Water Resour Assoc 34(1):73–89 Bao HJ, Zhao LN, He Y, Li ZJ, Wetterhall F, Cloke HL, Pappenberger F, Manful D (2011) Coupling ensemble weather predictions based on TIGGE database with Grid-Xinanjiang model for flood forecast. Adv Geosci 29(6):61–67 Bengtsson L, Hodges KI, Hagemann S (2004) Sensitivity of the ERA40 reanalysis to the observing system: determination of the global atmospheric circulation from reduced observations. Tellus A 56(5):456–471 Bengtsson L, Haines K, Hodges KI, Arkin P, Berrisford P, Bougeault P, Kallberg P, Simmons AJ, Uppala S, Folland CK, Gordon C, Rayner N, Thorne PW, Jones P, Stammer D, Vose RS (2007) The need for a dynamical climate reanalysis. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 88(4):495–501 Biemans H, Hutjes RWA, Kabat P, Strengers BJ, Gerten D, Rost S (2009) Effects of precipitation uncertainty on discharge calculations for main river basins. J Hydrometeorol 10(4):1011–1025 Brent RP (1973) Algorithms for minimization without derivatives. Courier Dover Publications, Mineola Author's personal copy Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 Castro LM, Salas MM, Fernández B (2014) Evaluation of TRMM Multi-satellite precipitation analysis (TMPA) in a mountainous region of the central Andes range with a Mediterranean climate. Hydrol Res. doi:10.2166/nh.2013.096 (in Press) Cheema MJM, Bastiaanssen WGM (2012) Local calibration of remotely sensed rainfall from the TRMM satellite for different periods and spatial scales in the Indus Basin. Int J Remote Sens 33(8):2603–2627 Chouakria-Douzal A, Nagabhushan P (2006) Improved Fréchet distance for time series. Data science and classification, Studies in classification, data analysis, and knowledge organization. Springer, Berlin, pp 13–20 Ciach GJ, Morrissey ML, Krajewski WF (2000) Conditional bias in radar rainfall estimation. J Appl Meteorol 39(11):1941–1946 Costa MH, Foley JA (1998) A Comparison of precipitation datasets for the Amazon Basin. Geophys Res Lett 25(2):155–158 Cressie N (1988) Spatial prediction and ordinary kriging. Math Geol 20(4):405–421 Dankers R, Hiederer R (2008) Extreme temperatures and precipitation in Europe: analysis of a high-resolution climate change scenario. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities Luxembourg, EUR 23291 Dosio A, Paruolo P (2011) Bias correction of the ENSEMBLES highresolution climate change projections for use by impact models: evaluation on the present climate. J Geophys Res Atmos (1984–2012) 116(D16). doi:10.1029/2011JD015934 Driemel A, Har-Peled S (2013) Jaywalking your dog: computing the Fréchet distance with shortcuts. SIAM J Comput 42(5):1830–1866 Ebisuzaki W, Kistler R (2000) An examination of a data-constrained assimilation. World Meteorological Organization-PublicationsWMO TD, pp 14–17 Ehret U, Zehe E (2011) Series distance—an intuitive metric to quantify hydrograph similarity in terms of occurrence, amplitude and timing of hydrological events. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 15:877–896 Faurès JM, Goodrich DC, Woolhiser DA, Sorooshian S (1995) Impact of small-scale spatial rainfall variability on runoff modeling. J Hydrol 173(1):309–326 Fekete BM, Vörösmarty CJ, Roads JO, Willmott CJ (2004) Uncertainties in precipitation and their impacts on runoff estimates. J Clim 17(2):294–304 Frechet M (1906) Sur quelques points du calcul fonctionnel. Rendiconto del Circolo Mathematico di Palermo 22:1–74 Gottschalck J, Meng J, Rodell M, Houser P (2005) Analysis of multiple precipitation products and preliminary assessment of their impact on global land data assimilation system land surface states. J Hydrometeorol 6(5):573–598 Grimes DIF, Pardo-Iguzquiza E, Bonifacio R (1999) Optimal areal rainfall estimation using raingauges and satellite data. J Hydrol 222(1):93–108 Hu C, Guo S, Xiong L, Peng D (2005) A modified Xinanjiang model and its application in northern China. Nord Hydrol 36:175–192 Huffman GJ, Bolvin DT, Nelkin EJ, Wolff DB, Adler RF, Gu G, Hong Y, Bowman KP, Stocker EF (2007) The TRMM Multi satellite precipitation analysis (TCMA): quasi-global, multiyear, combined-sensor precipitation estimates at fine scales. J Hydrometeorol 8:38–55 Huffman GJ, Adler RF, Bolvin DT, Nelkin EJ, Hossain F, Gebremichael M (2010) The TRMM multi-satellite precipitation analysis (Tmpa). Satellite rainfall applications for surface hydrology. Springer, Netherlands, pp 3–22 Kang K, Merwade V (2014) The effect of spatially uniform and nonuniform precipitation bias correction methods on improving NEXRAD rainfall accuracy for distributed hydrologic modeling. Hydrol Res 45(1):23–42. doi:10.2166/nh.2013.194 2019 Leander R, Buishand TA (2007) Resampling of regional climate model output for the simulation of extreme river flows. J Hydrol 332(3):487–496 Li H, Sheffield J, Wood EF (2010) Bias correction of monthly precipitation and temperature fields from intergovernmental panel on climate change AR4 models using equidistant quantile matching. J Geophys Res Atmos (1984–2012) 115(D10). doi:10. 1029/2009JD012882 Li XH, Zhang Q, Xu C-Y (2012) Suitability of the TRMM satellite rainfalls in driving a distributed hydrological model for water balance computations in Xinjiang Catchment, Poyang Lake Basin. J Hydrol 426:28–38 Li L, Ngongondo CS, Xu C-Y, Gong L (2013) Comparison of the global TRMM and WFD precipitation datasets in driving a largescale hydrological model in Southern Africa. Hydrol Res 44(5):770–778. doi:10.2166/nh.2012.175 Li L, Xu C-Y, Zhang ZX, Jain SK (2014) Validation of a new meteorological forcing data in analysis of spatial and temporal variability of precipitation in India. Stoch Env Res Risk Assess 28(2):239–252 Liu J, Chen X, Zhang J, Flury M (2009) Coupling the Xinanjiang model to a kinematic flow model based on digital drainage networks for flood forecasting. Hydrol Process 23:1337–1348 Maheshwari A, Sack JR, Shahbaz K, Zarrabi-Zadeh H (2011) Fréchet distance with speed limits. Comput Geom 44(2):110–120 Müller MF, Thompson SE (2013) Bias adjustment of satellite rainfall data through stochastic modeling: methods development and application to Nepal. Adv Water Resour 60:121–134 Nair S, Srinivasan G, Nemani R (2009) Evaluation of multi-satellite TRMM derived rainfall estimates over a Western State of India. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 87(6):927–939 Neitsch SL, Arnold JG, Kiniry JR, Williams JR, King KW (2002) Soil and water assessment tool theoretical documentation, version 2000. Texas, USA Nykanen DK, Foufoula-Georgiou E, Lapenta WM (2001) Impact of small-scale rainfall variability on larger-scale spatial organization of land–atmosphere fluxes. J Hydrometeorol 2(2):105–121 Oki T, Nishimura T, Dirmeyer P (1999) Assessment of annual runoff from land surface models using total runoff integrating pathways (Trip). J Meteorol Soc Jpn 77(1B):235–255 Omotosho TV, Oluwafemi CO (2009) One-minute rain rate distribution in Nigeria derived from TRMM satellite data. J Atmos Solar Terr Phys 71(5):625–633 Pan M, Li H, Wood E (2010) Assessing the skill of satellite-based precipitation estimates in hydrologic applications. Water Resour Res 46(9):W09535. doi:10.1029/2009WR008290 Parkes BL, Wetterhall F, Pappenberger F, He Y, Malamud BD, Cloke HL (2013) Assessment of a 1-hour gridded precipitation dataset to drive a hydrological model: a case study of the summer 2007 floods in the Upper Severn UK. Hydrol Res 44(1):89–105 Piani C, Haerter JO, Coppola E (2010) Statistical bias correction for daily precipitation in regional climate models over Europe. Theoret Appl Climatol 99(1–2):187–192 Rasmussen KL, Choi SL, Zuluaga MD, Houze RA (2013) TRMM precipitation bias in extreme storms in South America. Geophys Res Lett 40:3457–3461 Ren LL, Huang Q, Yuan F, Wang J, Xu J, Yu Z, Liu X (2006) Evaluation of the Xinanjiang model structure by observed discharge and gauged soil moisture data in the HUBEX/GAME project. IAHS Publ 303:153 Sawunyama T, Hughes DA (2008) Application of satellite-derived rainfall estimates to extend water resource simulation modelling in South Africa. Water SA 34(1):1–9 Scheel MLM, Rohrer M, Huggel C, Villar DS, Silvestre E, Huffman GJ (2011) Evaluation of TRMM multi-satellite precipitation analysis (TMPA) performance in the Central Andes Region and 123 Author's personal copy 2020 its dependency on spatial and temporal resolution. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 15(8):2649–2663 Singh VP (1995) Computer models of watershed hydrology. Water Resources Publications, Littleton Teutschbein C, Seibert J (2012) Bias correction of regional climate model simulations for hydrological climate-change impact studies: review and evaluation of different methods. J Hydrol 456:12–29 Uppala SM, Kållberg PW, Simmons AJ, Andrae U, Bechtold V, Fiorino M, Gibson JK, Haseler J, Hernandez A, Kelly GA, Li X, Onogi K, Saarinen S, Sokka N, Allan RP, Andersson E, Arpe K, Balmaseda MA, Beljaars ACM, Van De Berg L, Bidlot J, Bormann N, Caires S, Chevallier F, Dethof A, Dragosavac M, Fisher M, Fuentes M, Hagemann S, Hólm E, Hoskins BJ, Isaksen L, Janssen PAEM, Jenne R, Mcnally AP, Mahfouf J-F, Morcrette J-J, Rayner NA, Saunders RW, Simon P, Sterl A, Trenberth KE, Untch A, Vasiljevic D, Viterbo P, Woollen J (2005) The Era-40 re-analysis. Q J R Meteorol Soc 131(612):2961–3012 Varikoden H, Samah AA, Babu CA (2010) Spatial and temporal characteristics of rain intensity in the Peninsular Malaysia using TRMM rain rate. J Hydrol 387(3):312–319 Wang JF, Christakos G, Hu MG (2009) Modeling spatial means of surfaces with stratified nonhomogeneity. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 47(12):4167–4174 Wang JF, Haining R, Cao Z (2010) Sample surveying to estimate the mean of a heterogeneous surface: reducing the error variance through zoning. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 24(4):523–543 Wang JF, Reis BY, Hu MG, Christakos G, Yang WZ, Sun Q, Li ZJ, Li XZ, Lai SJ, Chen HY, Wang DC (2011) Area disease estimation based on sentinel hospital records. PLoS One 6(8):e23428 Weedon GP, Gomes S, Viterbo P, Shuttleworth WJ, Blyth E, Österle H, Adam JC, Bellouin N, Boucher O, Best M (2011) Creation of the watch forcing data and its use to assess global and regional reference crop evaporation over land during the twentieth century. J Hydrometeorol 12(5):823–848 123 Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2015) 29:2003–2020 Wu R, Kinter JL III, Kirtman BP (2005) Discrepancy of interdecadal changes in the Asian region among the NCEP-NCAR reanalysis, objective analyses, and observations. J Clim 18(15):3048–3067 Xu CD, Wang JF, Hu MG, Li QX (2013) Interpolation of missing temperature data at meteorological stations using P-BSHADE. J Clim 26(19):7452–7463 Yang DQ, Ishida S, Goodison BE, Gunther T (1999) Bias correction of daily precipitation measurements for Greenland. J Geophys Res 104(D6):6171–6181 Yao C, Li Z, Bao H, Yu Z (2009) Application of a developed GridXinanjiang Model to Chinese watersheds for flood forecasting purpose. J Hydrol Eng 14:923 Zhang DR, Zhang LR, Guan YQ, Chen X, Chen XF (2012a) Sensitivity analysis of Xinanjiang rainfall–runoff model parameters: a case study in Lianghui, Zhejiang province, China. Hydrol Res 43(1–2):123–134 Zhang ZX, Xu C-Y, El-Tahir MEH, Cao J, Singh VP (2012b) Spatial and temporal variation of precipitation in Sudan and their possible causes during 1948–2005. Stoch Env Res Risk Assess 26(3):429–441 Zhao RJ (1992) The Xinanjiang model applied in China. J Hydrol 135(1):371–381 Zhao RJ, Zhuang YL, Fang LR, Liu XR, Zhang QS (1980) The Xinanjiang model. In Hydrological forecasting, IAHS Publication(129) IAHS Press, Wallingford, pp 351–356 Zhao RJ, Liu XR, Singh VP (1995) The Xinanjiang model. In: Computer models of watershed hydrology. Water Resources Publications, pp 215–232 Zipser EJ, Lutz KR (1994) The vertical profile of radar reflectivity of convective cells: a strong indicator of storm intensity and lightning probability? Mon Weather Rev 122(8):1751–1759 Zquiza EP (1998) Comparison of geostatistical methods for estimating the areal average climatological rainfall mean using data on precipitation and topography. Int J Climatol 18:1031–1047