Journal of Peace Research

advertisement

Journal of

Peace

Research

Offprint from

No 2,

1968

U N I V E R S I T E T S F O R L A G E T

147

Table 1. Validation

FOREIGN POLICY T H I N K I N G I N T H E ELITE

A N D THE GENERAL POPULATION

A Norwegian Case Study*

By

H E L G E

International

Peace

H V E E M

Research Institute, O s l o

considerations are not paralleled by the

1. Introduction

T h i s article has two different, but to

a m o u n t of elite research actually carried

some extent overlapping purposes. T h e one

out. T h e r e seems to exist a certain dis-

is to present the world picture, or more

crepancy between elite studies a n d opinion

specifically

the

surveys, with m u c h stronger emphasis on

N o r w e g i a n foreign policy elite. T h e other

the latter. T h i s is not to say that this kind

is to contribute some new knowledge to

of research is unimportant: only that it

the

peace

thinking,

of

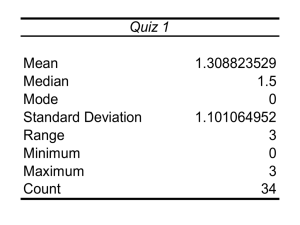

of the position of the elite and the opinion-TTUJ1cer sampks. %

Elite

Opinionmakers

36

60

12

84

26

36

35

1

9

79

16

46

53

24

7

'Would you say that you have any personal influence on the making of

Norwegian foreign policy?'

Yes ......•.................................•........••••.•

Little or no .........•......................................

'Have you been or are you at the moment member of any official Norwegian delegation to international organizations?'

.

Yes, 3 or more

Yes, 1-2 ................•...........••........•...•.......

No ...............•..••.•..........................•......

'When you discuss foreign policy matters, would you say that you yourseU

most often take contact with others, or are you more often contacted by

others?'

I most often take the contact myself

.

Both/it depends ..•.........................................

I am mO'it often contacted by others

.

12

cision-making structure ; their participation

A n o t h e r p r o b l e m is that of a possible

the general theory of foreign policy at-

should not be carried out to the neglect of

in official delegations to international or-

methodological bias d u e to different data

titudes as a function of social position,

elite research, as appears to be the case till

ganizations ; a n d their activity in the c o m -

collecting methods for the two samples in

n o w . Rather, one should concentrate m o r e

munication system ( T a b l e 1 ) .

large parts of the study. As far as we can

developed b y G a l t u n g .

1

4

see from our data, there seems to be no

T h e data presented are part of the results

on studying the relations between elite a n d

O u r assumption is verified on all three

obtained from a study carried out a m o n g

public opinion, by m o r e extensive c o m -

variables: the elite sample scores higher

clear

two different population samples repre-

parative research. T h i s is our second start-

on all of them. T h e third variable, h o w -

of such a bias. We m a y show this by c o m -

ing point or m a i n 'hunch', which will be

ever, needs some further c o m m e n t s .

paring

senting higher strata in N o r w e g i a n society.

2

O n e group, the foreign policy elite,

was sampled according to a design used

further elaborated below.

W e assumed that the opinion-makers t o

T h e data were collected in two slightly

some

extent

influenced

or

tried

to

tendency

or

responses

indications

on

items

generally

which

were

presented in m u c h the same context a n d

in-

formula in both the interview guide a n d

the questionnaire, a n d comparing, on the

policy elite

fluence the elite: this is in fact indicated

level

was interviewed by the author and three

by the scores on the question of w h o con-

the other h a n d , responses the elite gave

between the elite a n d the general public

assistants, trained in this technique, from

tacts w h o m the most. T a k i n g the ratio

on interview a n d the opinion-makers on

opinion — educating or forming the latter,

February to Ap ril 1 9 6 7 with the use of a

between 'contact m y s e l f

questionnaire stimuli. A n attempt t o c o m -

a n d to some extent influencing the former.

mostly pre-coded a n d wholly structured

by others', we find that the ratio of the

bine

T h e sampling procedure is explained in

interview guide. This group was also asked

elite is 2 / 3 : the elite is m o r e often con-

T a b l e 2 . Unfortunately, w e m a y present

A p p e n d i x A , together with some data o n

to answer some questions on a question-

tacted by others than itself contacts others;

only two items which were used in both

the composition of the two groups.

naire. T h e responses of the opinion-maker

the position of the opinion-makers is the

the guide a n d the questionnaire : the intra-

reverse.

and

by other authors.

opinion-maker

3

T h e other group, the

group,

represented

a

Elite studies are important for several

different

sample

ways.

were

T h e foreign

given

on

a

questionnaire

a n d 'contacted

these

the

t w o approaches

inter-individual

is

m a d e in

approach

to

peace.

reasons. T h e cognitions a n d evaluations

which, except from a few questions, was

Contacts, of course, m a y be taken b o t h

of elite persons are of consequence to the

pre-coded. T h e opinion-maker study was

vertically a n d horizontally. T h e opinion-

formation of a country's foreign policy.

carried out in the period from A pr il to

makers m a y contact the elite — a n d it has

about

W h a t the

been shown that this happens m o r e often

on the intra-individual item, the opinionmakers are m o r e positive in b o t h cases

T a b l e 2 supports our general conclusion

a

possible

methodological

bias:

opinion-maker

medio June the same year. T h e methodol-

strata see a n d believe about the world is

o g y used is explained in m o r e detail in

than

important;

Appendix B.

makers; in other words: the structural or

(81%

positional difference is clear. But contact

35 %) ; on the inter-individual item the

elite

and

it even

the

to some extent d e -

the

elite

contacts

the

opinion-

against

78%,

and 4 6 %

against

termines what the rest of the population

Before we proceed, let us briefly validate

shall see or believe. Internal structures of

the assumption m a d e above that the elite

may

opinion-

elite is the most positive on both cases.

If we read the T a b l e vertically a n d look

also

be

taken

between

a n d the opinion-maker samples do rep-

makers. Since the question, however, was

the structure of a n d intensity in the rela-

resent different social strata. This we do

m a d e in a context where the focus was on

at the relations between the two items, the

tions with the outside world are factors

by

the

policy,

trend is also consistent in all four cases (of

which work in this direction.

variables : the respondents' o w n perception

vertical or u p w a r d contact was evidently

positive evaluation) : the intra-individual

of their position in the foreign policy de-

in the minds of most of the opinion-makers.

approach is the most preferred.

communication a n d decision-making, a n d

In our opinion these generally-accepted

presenting

data

on

three

different

top

level

making

of foreign

149

148

Table 2. Test

of the data collecting method. %

Interview guide8

E

OM

Individuals educated to peace

Better relations between the indiv.

Pos

78

56

Questionnaire

E

OMb

Neg

Pos

12

81

Neg

12

35

22

51

25

28

46

27

a The data for the opinion-maker sample are based on responses on a questionnaire.

The percentages here represent those who think that the item is 'Especially important to

peace'.

b

E = Elite; OM = opinion-makers.

Another point to be mentioned in connection with a possible data collecting

bias is that no decisive event appeared on

the world scene during the time of the

opinion-maker data collection to make the

scene markedly different from the one the

elite (in an earlier period) had before their

'eyes'.

5

2. The Norwegian foreign policy elite:

some assumptions

H o w does the Norwegian elite perceive

and evaluate its international environm e n t ? This is the question which will

o c c u p y us here. T h e more general question

of h o w elites as such picture the world is

— provided there are certain features in

elite thinking specific enough and c o m m o n enough — an interesting problem

which shall not be dealt with here (and

which, by the way, needs a lot of data

for comparisons, both among elites and

between elites and national public opinion

groupings).

To point at some possible answers to our

question, which we will relate more

specifically to the peace thinking of the

Norwegian elite, we m a y look into several

sets or categories of data: social background, personality, predominant attitude sets. This individual level approach

can be compared to or replaced by a

national level approach: national characteristics like degree of cohesion or h o m o geneity, culturally, socially, and politically,

or social development are examples of

variables in this approach; or an international level approach, with use of variables like the rank of N o r w a y in the

international system, its memberships in

regional groupings with specific culture,

ideology, polity, etc.

We shall not explore systematically

these different possible approaches to an

explanation of the Norwegian elite thinking, but merely point to some features we

believe basic to such an explanation.

Generally, we believe that social background variables so often used in opinion

surveys are of little use in this context;

this is shown convincingly by Edinger and

Searing. Studies using the national level

approach show that Norway is a relatively

homogeneous, consensus-motivated country, although there is some dispute on the

degree and exact 'type' of homogeneity.

6

7

We feel that the international level approach in important respects is the most

interesting and possibly the most fruitful

in this context. As N o r w a y is a small

country (on several variables used to

measure magnitude) with little influence

on world affairs and peace-or-war matters,

her elite or decision-makers are to a large

extent influenced, in their thinking and

policies, by outside events and actors.

It is therefore basic to our problem what

position Norway has in the system.

Briefly, Norway's position is that of a

center country. A center country (as

opposed to a periphery one) is centrally

placed in the communication network, is

rich (high G N P and/or G N P per capita),

is urbanized and industrialized (i.e.

' m o d e r n ' ) , is white. Its world view will

largely be determined by its position:

it has m u c h to defend — greater and more

values than the periphery nation. On a

'radical vs. conservative' dimension, it will

tend towards the conservative e n d : it will

be status quo- more than change-oriented;

will prefer stability in international relations and thus tend towards stability in its

o w n p o l i c y ; will be gradualistic and not

absolutistic.

8

T h e small center country like N o r w a y

will not aspire to a higher rank or position

in the system: it will be content with its

high rank on several important dimensions

(development, etc.) and accept the fact

that it is l o w on influence and power,

although this points to a certain disequilibration in its total rank. T h e small nation,

however, may increase its influence through

international co-operation; we expect this

assumption to be strongly held among

elite persons in a center nation like

Norway. Such an assumption may be

based on evaluations of co-operation experiences as such; or it may be explained

by sheer necessity: N o r w a y is economically

(and is at least perceived to be so militarily) dependent on the outside world,

more specifically Western co-operation.

This fact, together with its general p o sition and the feeling that Norway's

influence does not reach very far, means

that the Norwegian elite will emphasize

middle-range or middle level world perspectives — be regionalistic or subsystem-oriented more than globalistic.

9

10

3. Peace thinking: an elite profile

Operationally, we shall think of a profile as a set of responses to stimuli which

present concrete aspects of international

life. T h e profile has both cognitive and

evaluative elements.

T h e respondents were asked several

questions on the present and the future

world situation which inter alia elicited

their perceptions and evaluations of international conflict potential and actual or

possible threats to peace. Here we shall

only note that the Norwegian elite seems

rather optimistic about the future world,

which it believes will be more integrated,

more co-operative, less conflict-dominated,

partially disarmed, m o r e dominated by

technology, and at least as egalitarian

(concerning the gap between rich and

p o o r countries) as today, and more developed generally.

Before we proceed to the peace profile,

let us ' o p e n ' the minds of the elite persons

by giving their preferences for an immediate or short-range peace policy (Table 3 ) .

T h e y were asked what measures they

deemed the most important to-day to

secure international peace. T h e responses

may be compared with responses on the

list of peace proposals which will be presented below and which implies the more

principal or long-range preferences of the

respondents. T h e short-range preferences

may also be used to validate the long-range

ones.

Table 3. Preferred immediate peace-making

measures. %

Strengthen international co-operation/the

UN

24

Further East-West détente and understanding 17

Keep the balance of power

10

Agreement on non-proliferation treaty...

10

Disarmament and arms control measures.

9

Close the 'gap' between the rich and poor

countries/give more TA and aid to development

9

Solve the Vietnam conflict

3

Other

10

NA/DK

8

Total

100

(N)

(88)

T h e preferences go clearly in the direction assumed: co-operation and stability.

Elite preferences for main short-range

goals of Norwegian foreign policy underline the tendency: détente and co-operation

rank on top (with 2 5 % and 1 7 % , respectively). Let us then turn to the peace

profile.

11

151

150

Table 4. Th optiTTUll peace profile of the elite. %&

Proposal/

item

number

14

4

6

13

9

10

15

8

3

11

2

16

Proposal is:

We must strengthen the UN ........

Abolish hunger and poverty in the

world .........................

Rich countries must give more help to

poor ............................................

Western countries must increase contact with East .........................

General and complete disarmament

must be realized ...............

There must be a military balance between the states so that nobody

dare'! to attack ......................

We must strengthen regional organizations ..............................

The military alliances must be preserved ........................

The states must become more democratic ...............................

The individual man must be educated

to peace ......................

Statelt that naturally belong together

must co-operate .......................

Relations between individuals must

become more peaceful ..........

The World State must be established

as soon as possible

There must be fewer states in the

world ...................................

The small countries must have greater

influence ..................................

The nations must become more similar

.......

12

7

5

&

'Espe- 'Some'Unimdally

what portant 'Against

impor- importo

peace'

tant to tant to peace'

peace' peace'

0

..............

A/

DK Total

79

17

0

0

4

100

69

21

3

0

7

100

60

31

60

29

4

58

19

4

58

25

3

0

5

100

0

10

100

0

19

100

13

100

42

47

3

0

8

100

38

42

3

4

13

100

36

46

13

0

5

100

35

55

10

0

0

100

28

47

10

14

100

28

33

21

18

100

24

15

18

42

100

10

22

47

20

100

8

7

47

45

23

31

22

16

100

100

0

0

1

N = 72, as 16 of the total 88 in the elite sample did not fill out the questionnaire.

A list of peace proposals was presented

to the respondents in a questionnaire.

This list of 16 items of course does not

contain all the important, relevant p r o p o sals which have been put forward, but it

does represent a fair sample of such proposals, selected to meet certain purposes.

In T a b l e 4 the numbers at the left indicate

in what order the proposals were presented

to the respondents; these numbers will

later be used to represent the particular

proposal.

T h e proposals are in T a b l e 4 ranked

according to degree of favorable responses

they got, i.e. according to preference. This

ranking gives us the ideal peace-making

programme of the elite — what we shall

call its 'optimal peace profile'.

We see that the results presented in

T a b l e 3 to a large extent resemble and

thus validate the optimal peace profile.

Co-operation (items 14, 15, 8, and 11)

ranks high, détente (item 13) also. N e w is

that measures connected with the p r o b lems of the developing and p o o r countries

rank high (next to strengthening the U N )

in the profile, while they rank l o w on the

list of immediate peace-making measures

(Table 3) and on preferences for Norwegian foreign policy. This means the

developing countries and the ' g a p ' are

perceived as more long-range problems;

in fact, responses on a question of predictions about future problems or tasks

fit very well with this argument. O r :

the elite talks about these problems b e cause they are part of a general b o d y of

items which one ought to talk about nowadays; but it does not work them into

p o l i c y ; or it postpones their policy implications.

12

T h e varying N A / D K responses m a y

explain some of the variance in the

'especially important to peace' category,

which we use as the basis for ranking.

Apart from the disarmament item, h o w ever, most of the items high on N A / D K

are at the bottom of the list anyway: they

are seen as decisively less important. In

general, a high N A / D K score may be

taken as a sign of uncertainty as to whether

the proposal is peace-making or not.

W h a t we have called the optimal peace

profile is not necessarily indicative of policy

preferences. Before becoming policy, the

ideal peace programme passes through

a 'filtering' process, or several processes.

O n e such 'filter' is the respondents'

perceptions of h o w 'the real world' meets

the ideal proposals and makes them

'realistic' — applicable or workable — or

not. Another 'filter' is the fundamental

attitudes or personality structures of the

respondents.

In fact these and other possible filters

influence each other and jointly influence

peace thinking; they are isolated for

theoretical purposes. T h e use of the c o n cept filter may also be somewhat misleading : in the mere evaluation of the different

peace proposals (the optimal profile) both

both affective and cognitive factors are at

work. T h e cognitions of the respondent

m a y have a decisive influence on his preferences, making him prefer what he perceives as realistic, and vice versa. Thus it

m a y be incorrect to say that the filter

comes in at a second stage in the process

of profile building.

However, the exact 'place' of the different factors in the processual sequence

is not a main problem here, or an especially

relevant one. T h e process is schematically

presented in Figure 1. T h e end result of

the process — the policy outcome — we

shall call the 'operational peace profile'.

I

I

(filters)

I fundamental

II

~I attitudeS'YalUe~

Optimal I<!

I

peace

I

profile

I

t

I

I

I

~

~:cO&nit::ns,p}rcePtionl

(preferences'

ideolou)

I

I

Operational

peace

profile

of "real world"

(policy)

I

Fig. 1.

Fundamental attitudes which may work

as a filter are for instance 'anti-communist'

feelings, which 'filter out' East-West

détente, or regionalism — strong loyalties

to specific regional co-operation frameworks — which will to some extent 'filter

out' the globalistic proposals represented

by ' W e must strengthen the U N ' (at the

cost of ' W e must strengthen regional c o operation'). In fact, both examples are

supported by our d a t a .

13

In the following, we shall concentrate

on the cognitive filter in the process. It

was introduced simply by asking the

respondents if the believed that they respective proposals for world peace were

'realistic' or 'unrealistic' — whether or

not they might be carried through in the

short or in the long run. T h e results are

shown in T a b l e 5. By calculating the percentage difference between the preference

and the perceived 'realism' of the specific

items, we get the 'trust status' of each item.

If a highly preferred proposal is seen as

highly unrealistic, this proposal represents

an extremely (fotrusted peace proposal.

A highly realistic proposal which is less

preferred might on the contrary be called

a trusted peace proposal, etc. We shall

155

I52

Table 5.

5. Perceptions

Perceptions of

of'realistic'

',ealistu' peace

peaee proposals:

proposals :the

theelite.

elite. %

%

'Especially

important

'Realistic'

,

to peace'

peace

r

Strengthen the UN ...••..............•.....

Abolish hunger and poverty .................•

Rich countries help poor ...•..•..•.........•

West contact with East .•....................

G & C disarmament •......................•

Military terror balance

.

Strengthen regional org's •........••.........

Preserve alliances

.

More democratic states ......•...............

Individual educated to peace ..••........•..••

Co-operation between 'natural partners' ......•

Better inter-indiv. reI. ......•.....•...•..•...

World State realized as soon as possible .....•..

Fewer states in the world ..................•..

Small countries more infl. . .•................

Nations more similar .................•......

79

69

60

60

58

58

42

38

36

35

28

28

24

10

8

7

61

42

·"••lIlm'

peru:ptlon

«

_

'Un, j . .%.

realistic'

diHerel

realistic

difference*

U n

7

26

64

7

69

0 /

-18

-27

49

10

70

36

3

33

68

6

10

74

63

46

61

I

4

32

25

50

24

10

Medium

14

I

35

74

46

26

7

-18

9

32

25

39

19

68

35

6

19

33

26

40

a

19

60

We shall use another method of grouping, however: a differentiation on each

dimension of the c o m b i n e d preference —

realism perception scale between three

levels: high, medium, and low. This

method gives us four groups of proposals:

HighjHigh: proposals 13, 10, 6 and 14

High/Medium: proposals 1 5 , 8 , 4 , 1,9 and 11

Medium\Medium: proposals 3 and 2

60

'9

'- -- - -------~~Q- --- --_.-

-40

2

o

70

I

L

30

Medium/Low, or

Low/Low: proposals 7, 5, 16 and 12

T h e broken lines in the Figure indicate

the cuts between the three levels mentioned; the range of the levels are somewhat larger on the 'realism' dimension

because of the higher average percentage

score on that dimension. T h e cuts roughly

are m a d e according to the clustering

trends where the distance between t w o

items following next to each other on the

dimension in question is the greatest.

T h e order of listing the different p r o posals also may indicate their relative rank

within the cluster or group, since it corresponds roughly to their distance from

the broken line indicating the level they

are closest to.

T a b l e 5 shows that on several items the

difference between degree of preference

and degree of realism perception is c o n siderable. This largely answers questions

about the relation between affective and

cognitive aspects in the respondents' thinking.

---- ------

50

20

Low

12 0

10

160

10

Figure 2 indicates 7 clusters of items,

if arithmetical proximity is taken as a

measure of clustering: 13, 10 and 6; 14;

1 5 , 1 1 , 1 and 8; 4 and 9; 3 and 2; 7, 5 and

12; and 16.

10 0 0

9

-22

Difference 'Realistic' — 'Especially important to peace'. The average score for all 16 items

was 8% higher on the response 'Realistic' than on 'Especially important to peace' — 4 8 % and

4 0 % , respectively. For a better or more direct comparison between the different proposals, we

might take a weighted difference score where the average percentage difference is taken into consideration, i.e. — 8% is added to each difference score in the right column.

soon return to this problem. Let us first

present the operational peace profile of

the elite.

We do this by 'sewing' the two dimensions — preference and perception of

realism — together in one matrix, where

the y axis represents realism, the x axis

preference. We plot in the percentage of

each single item on each of the two axes

and get one point in the matrix for each

item. This is shown in Figure 2 (next p a g e ) .

13

11

HI&h

20

Low

30

50

-40

Medium

70

60

80

HI&h

Preference

Fig. 2

A more general test of this difference is

the Spearman's rank correlation. Correlating ranks on the preference and the

'realism' perception dimension, we get a

rho of 0.33, which gives even better support

to the conclusion that the affective-cognitive difference is considerable. How c o n siderable it is, however, must be decided

on a comparative basis. Festinger has

worked with and given possible solutions

to the problem of cognitive dissonance.

We believe that m u c h of what has been

said about that problem can be applied to

the problem of affective-cognitive differences or dissonances.

We shall test the hypothesis that the elite,

in spite of the difference or dissonance

found, is relatively more affective-cognitive

consonant than other (or lower) social

strata. M o r e generally, the hypothesis is

that consonance increases with increasing

14

social position. While we shall not be able

to test satisfactorily here this general

hypothesis, let us compare the elite and

the opinion-makers, on w h o m we have

comparable data.

T h e basis for the first mentioned hypothesis is the assumption that the elite person 'cannot live with' a very dissonant profile; this is more or less inconsistent with

his position. He is largely responsible for

policy-making. In the feed-back system

of deciding policy, carrying it out, and

receiving reactions to it, there will

generally be a process of adjusting the

cognitive and affective aspects to each

other, so that the two sides of the dissonant

affective-cognitive structure converge; or

so that one side is made more concordant

with the other, unilaterally.

For example, when policy initiated by

the optimal peace profile meets drastically

154

155

a

Table 6. Most 'trusted' and 'distrusted' peace proposals

Most 'trusted'

.

40

32

26

25

17

Abolish hunger and poverty in the world

General and complete disarmament . . .

Strengthen the UN

Establish the World State

—27

—22

—18

—18

For explanations and comments, see footnote to Table 5.

and/or several times in a sequence of

policy initiatives, with a reality which was

not presupposed, and the policy does not

work, the ideal policy is m a d e more c o n cordant with reality.

Another reasoning speaks against the

hypothesis. There m a y in a foreign policy

elite be some influx of 'quasi-preferences' —

peace policies preferred as a tribute to

e.g. the democratic structure of the society,

but not really felt. M o s t elite persons are

representatives of (in some cases dependent

upon) other strata — the people, and must

pay 'lip service' to peace thinking strongly

held in influential parts of the opinion.

T h e y compensate for this 'restriction'

of their o w n true ideology by degrading

the 'tributary' peace philosophies on the

cognitive side, i.e. making them 'unrealistic'.

This point m a y be seen as another or

third filter mechanism. Furthermore, it

m a y explain the considerable cognitiveaffective dissonance in the case of our elite

sample. We still think, however, that our

hypothesis is reasonable. This is also verified, as the opinion-maker sample has a

Spearman's rho of — 0 . 1 0 .

1 5

Another expression of the cognitiveaffective dissonance is the 'trust' or 'distrust'

of the different proposals, already introduced. T h e measure of trust is the percentage difference between 'realism' perception and preference, as shown in

T a b l e 5. In T a b l e 6 we give the most

'trusted' and the most 'distrusted' proposals. T h e last item in each column is not

evaluated as having m u c h importance to

peace and will be left uncommented here.

T h e others point to a clearer picture of the

content of the cognitive-affective dissonance and to some propositions for

further research.

T h a t the 'Start with the individual'

approach is so m u c h trusted is probably

due to a general ideology in the N o r wegian society, stressing individualism and

possibly Christian conceptions of man's

duties and deeds.

A comparison of the two arms policy

items listed in T a b l e 6 — 'Disarmament'

and 'Preserve alliances' — indicates that

'tough' proposals are trusted, 'soft' ones

distrusted (the two proposals mentioned

taken to represent 'soft' and 'tough' policies, respectively). T w o other arms

policy proposals — ' K e e p the balance'

(tough) and ' M o r e West contact with

East' (soft) — do not support such an

hypothesis, however, even if they do not

go against it (cf. T a b l e 5 ) . This point

needs more exploration.

That to abolish hunger and poverty all

over the world emerges as the most distrusted, is not astonishing. M o r e interesting and perhaps remarkable is that to

strengthen the UN — the proposal ranking

in the top category of the operational

peace profile — ranks number three

among the most 'distrusted' proposals.

This literally breaks the neat line which

the profile is drawing u p : to strengthen the

U N , although ranking top on both the

optimal and the operational profile, will

'in the real life' of politics or policy-making

be a less attractive or useful proposal, i.e.

more of the H i g h / M e d i u m type of proposals.

Even more convincing is such an argument if we assume — as we feel is quite

%

Level

Optimal

profile

average

Realism

perception

average

Optimalrealistic

diHerence

average

Global

.

Inter-regional ..............................•...

Intra-regional ..........................•...•...

ational

.

Sub-national/indo

.

57.5

54.0

35.0

15.25

31.5

36.5

66.0

71.0

31.0

48.0

-21.0

12.0

36.0

15.75

16.5

Most 'distrusted'

Co-operation between natural partners

Strengthen regional organizations

Educate individuals to peace

Preserve alliances

More influence to small states

a

Table 7. Level orientation in elite peau thinking.

fair — that policy-makers stick to 'realistic

policies' if they have to choose between

the preferred or optimal and the 'realistic',

or if they see that the m u c h preferred

but not so m u c h 'realistic' policy line over

time is not working or even does not turn

out as m o r e 'realistic'. Thus we have to

upgrade the 'realist' perception side of

the operational profile, which in turn

means that the M e d i u m preference/High

realism proposals emerge as relatively

more operational. A n d — it means that

the regionalistic, middle-range proposals,

which also are the most 'trusted', b e c o m e

the policy.

This was exactly what we assumed or

hypothesized: regional peace policies are

m o r e operational than global ones in the

thinking of the elite. ('Alliances' and

'natural partners' generally indicate regionalism.) T h e regional-global dimension

moreover, raises a problem of a m o r e

general character: whether and to what

extent one or more specific level in the total

international system is preferred for peacemaking policies. (By the 'total international system' we think of a structure

ranging from the global (top) system level

to the individual (bottom) intra-personal

level.)

O n e of the purposes of the choice of

proposals presented was that they should

represent the different levels of the system.

It may be discussed whether or not the

representation is the best one or even satisfactory; this will not be done h e r e . Let

us briefly show the structural set-up (levels

specified) and which items represent the

different levels:

16

global items

interregionala "

intraregional

"

national

"

subnational

"

individual "

1,2,5, 13

3, 4, 6, 8

7, 11

9,14,15,16

I

I Item

numbers:

see

Table 4

12

10

a

This is separated from 'global' because it

stresses relations between specific groupings in

the global system, — rich versus poor countries, East versus West, etc.; it may, in that

respect, also or even more be separated from the

regional (= intra-regional) level.

T h e two lowest levels, the sub-national

and the individual ( = intra-personal), are

c o m b i n e d in T a b l e 7; the distinction b e tween them is not essential to our problem

here. We get what m a y be called the level

orientation of the elite by taking average

scores for all items categorized as shown

above.

In T a b l e 7, the regional-global dimension is even better evidenced. T h e ' W o r l d

state' proposal, which scores extremely low

on 'realism' and very l o w on preference,

of course contributes heavily to the relative

l o w average score on these two variables.

Even excluding this item, however, the

optimal-realistic difference or discrepancy

is not reduced: indeed it is slightly increased (the scores being, in the order

indicated in the T a b l e , 6 9 , 4 6 , and 31 % ) .

From all this, we m a y conclude that the

Norwegian elite in its thinking about

peace does not ' g o to extremes': it neither

prefers, neither perceives as very realistic

156

157

Table 8. Affective-eognitiDe dissoTIiUIU and personality types

Table 9. Elite versus opinion-makers on some selected proposals. %

Preference :

H~

High

'Realism' perception:

UW

The consonant or well balanced 'The cynic' or 'The sheer realist'

uw

'The sheer idealist'/

'The disillwioned'

the ' W o r l d state' or ' O n e world' approach

nor the 'Start with the individual'

( U N E S C O , psychological) or the 'group

therapy' (inter-individual, micro-sociological) approach to peace. An operational

Norwegian peace policy which seems to put

emphasis on the m e d i u m level while the

optimal is on the global, reflects again the

feeling on the part of the elite that Norway's foreign-policy-making possibilities

(and to a certain extent peace-making possibilities generally) are on the regional level.

T h e question of affective-cognitive dissonance raises the p r o b l e m : what are the

possible or probable consequences of dissonance, especially to individuals with a

highly dissonant p r o f i l e ? A m o n g other

factors, this depends on the intensity with

which the ideas concerned are held, how

unrealistic they are thought to be, and

for how long such feelings and thoughts exist.

17

A person with a peace profile high on

preference, l o w on realism may be a 'sheer

idealist' able to live well with his dissonant

peace thinking. Or he may not be able to

do that and end in frustration or disillusion,

which m a y further result in forms of

desperate action, or in inaction. He will

perhaps blame the world ('it is rotten,

nothing will work') or his leaders ('they

don't want peace, really'; 'they are the

true causes of w a r ' ) . A study of the British

Peace Pledge U n i o n — an organization

of 'radical peace activists' — has given

some evidence on this.

18

Another position m a y be that of a

' c y n i c ' or 'realist': peace proposals are

not highly preferred or evaluated, but the

measures or methods they indicate are

seen as quite realistic. T h e various per-

'The withdrawer:

the out of-this-world man'

sonality types we may draw from such

reasoning on affective-cognitive dissonance can be listed schematically as in

T a b l e 8.

Consonant personalities are found on

the L o w / L o w to High/High diagonal axis.

T h e elite person will generally be found

at the High/High end of the axis, while

lower social strata will spread to the other

four categories. But there are, as has been

shown, important exceptions to this picture: a considerable part of the elite is

placed in one of the two dissonant High/

L o w categories.

T h e opinion-makers, w h o were shown

to have a more dissonant profile than the

elite, are more free to be dissonant and (at

least from some parts of society) probably

are expected to be more so. This group,

standing between the elite and the general

opinion, in some respect must represent

both 'sheer realism' and 'sheer idealism':

it shall compensate for the lack of such

positions or personalities in the elite and

at the same time give vent to such more

or less manifest attitudes among the

general opinion.

T h e relative dissonance among the

opinion-makers seems to be in particular

due to a greater percentage of 'idealists'

in the sample. This is indicated by T a b l e 9,

which contrasts the elite and the opinionmakers on some selected items. T h e

opinion-makers are shown as more 'soft'

and more 'idealistic' (believe more in the

individual and the W o r l d State approach).

Interestingly, while the two samples differ

markedly on the preference they attach

to the different proposals, there is striking

agreement between them as to h o w

Keep the balance

Preserve alliances

Educate individuals to peace

Establish the World State

.

.

.

.

'realistic' they deem the poposals to b e .

This explains m u c h of the relative dissonance of the opinion-makers.

4. The projection hypotheses

In 4.1 we test what we shall call the

ultra-center hypothesis; in 4.2 we shall test

some assumptions about differences b e tween the elite, the opinion-makers, and

the general opinion.

Data for the test of these hypotheses

will cover peace thinking, attitudes toward

several important foreign policy dimensions, and attitudes toward disarmament.

These data are taken from the author's o w n

study, from several general opinion surveys

conducted in N o r w a y from 1964 to 1967,

and from a youth study m a d e at the end

of 1967.

4.1. The ultra-center hypothesis

Galtung's theory of foreign policy

opinion as a function of social position

is n o w well established. O n e specific

aspect from this theory will be the object

of our analysis: the idea that we may project the opinion of one or more social

groups, whose opinion we want to know,

from the opinion (which is known) of

other social groups, if we know the social

position of these last groups and position

of the group (s) whose opinion we want,

relative to those groups. Social position is

determined by use of the Galtung index of

social rank. T h e projection idea implies

that we literally m a y draw a line through

the opinion scores of the rank categories

on the scale from 1 to 8. O u r hypothesis

is that the foreign policy elite by o p inion is an ultra-center, i.e. by opinion

represents a 'prolongation' on the peri20

'Especially

important to peace'

E

OM

58

34

38

22

35

.w

24

36

'Realistic'

E

OM

68

64

63

61

6

63

59

10

phery-center line of the center (category 8 ) .

T h e hypothesis evidently raises several

problems and even objections, some methodological, some theoretical. O u r original

study was not built on the social position

index; consequently, we are not able to

assert the position of the elite on that

index. We may, however safely say that it

is not on the average rank 8, rather something between 6 and 7 .

21

Furthermore, Galtung's theory is built

on the conception of society as a system

ranging from periphery (0) to center (8)

— there is no rank 9 or 10 or anything

'outside' the system. T h e projection idea

thus seems both theoretically and logically

irrelevant. O u r hypothesis, however, is

based not on this conception of the system

with definite 'borders', but on the very

opinion curves which the system produces.

Generally, the problem is this: where does

the elite stand in relation to such a curve ?

It was mentioned that the elite is not

a center group (according to the 8 variables

of the Galtung i n d e x ) : does it not follow

from this that the hypothesis is unreasonable ? This is not the case.

Several dimensions, which may be called

structural factors and which do not go into

the social position index, explain the point.

T h e elite is placed within or close to the

society's nucleus of foreign policy c o m munication and decision-making. It c o m municates m o r e extensively and intensively about foreign policy and international political matters, than other

(secondary) social groups. Thus, socialization to opinions dominant within

the elite is relatively intense and effective;

159

158

M o r e crudely, the center (8) is not

structurally sewn together as the elite is

— it is a social category, not a social group.

Y o u can socialize people in that category

because they pay more attention to information and opinions circulated, but

y o u cannot exclude deviant persons from

it as y o u m a y do through recruitment and

promotion in the elite.

,

,0"

:

:

// 1

/

I

:.t:---~

opinion

posItiOn

1- _

I

I

I

-_

,

I

I

I

I

I

8

I

-9 c

I

nnk 8

rank 0

I

I

I

The elite

social position

Fig. 3

social position

Fig. 3

Another p r o b l e m is the question of what

implications to society and to the elite

itself the opinion position of the foreign

policy elite, relative to that of other social

strata, might have under specific conditions. T h e problem is illustrated in Figure

3. T h e unbroken line from 0 to rank 8

is arbitrarily drawn. Three possible elite

opinion positions are indicated by A, B,

and C. T h e y have different consequences

for the relations between the elite and the

rest of society.

W h a t further implications these systems have or m a y have depends on the

society — whether it is homogeneous (on

other dimensions than foreign policy

matters), developed, informed or educated, content with the foreign policy in

question and has the means to criticize

and sanction the elite etc. — and on the

elite — what role it plays or is supposed

to play: whether its role is to initiate, to

lead or guide the opinion, or to go only

as far and as fast as the average opinion

is willing to g o . W h a t system is the most

stable in the sense that the elite's opinion

position is accepted and will be the basis

for policy over time? W h i c h system is

the more efficient in the way that policies,

once decided upon, are carried out and

work?

In the case of Norway, it is tempting to

say that the system B will be the most

stable and probably also the most efficient.

B avoids an opinion gap which m a y be

disastrous in splitting the society, it fits

well into a relatively educated and foreign

policy interested society, and it avoids

challenges to the elite from the center.

In system C, we might expect that the

center w o u l d produce opposition towards

the elite's opinions and policies because

they were 'lagging behind' their own, and

stand out as an alternative elite, challenging the existing one.

22

Table 10. The ultra-center hypothesis: ratio of positive to negative response

Norway should continue in N A T O

Norway should become a full member of the E E C *

Norway should give help to developing countries

that want to build their own merchant marine

Norway should give customs duty preferences to

developing countries

Norway should make closer ties with:

NATO/Nordic countries

Average ratio

CO

m u c h the same information is distributed

and consumed a m o n g elite persons. Furthermore, individuals are recruited to the

elite much on the basis of allegiance to

such dominant opinions ; and expectations

of within-elite career make for conformity.

Generally, there is a relatively strong

building-up of consensus. It is definitely not

1 0 0 % : there are some alternative opinion

formation channels within the elite, as

indicated by the peace thinking differences ; but these generally cover only small

minorities, because m u c h of the meaning

of an elite set-up with most of the decisionmaking responsibility attached to it is

to keep those channels narrow and sparsely

populated.

A represents the 'autocratic' foreign

policy system; the distance between the

elite and the rest, including the center

categories, is great (measured along

the vertical axis; the distance from the

point rank 8 to the elite on the horizontal axis is arbitrary and only for

illustration purposes); there is an

'opinion gap' between the elite and the

different opinion strata. B is the

'guided democracy' model, or the oligarcic

model. In this system the elite stands

close to the center of society, reflects

centrist opinion, is possibly recruited

by the center. C is the 'democractic'

system where the elite reflects and

represents a medium or an average of

the opinion of the whole society.

1

3

6

1.5

0.8

1.6

1.0

2.9

1.9

3.6

2.7

Elite

17.2

7.7

0.5

0.5

0.7

1.0

1.5

0.5

0.2

0.4

1.2

3.7

0.4

0.7

0.4

0.7

0.5

1.3

0.7

1.8

2.0

6.4

* The data for the rank categories are taken from a national survey made in 1964 which gave

a total of 4 4 % for, 3 3 % against a Norwegian application for full membership in the E E C . A similar

survey made in 1967 gave 5 4 % for and 2 1 % against. Thus the ratios for the rank categories are

higher now, probably much like those given on the question of N A T O .

Considering that Norwegian foreign

policy generally has not been and is not

very m u c h disputed, it is equally tempting

to hypothesize that the Norwegian system

actually is of type B, and that the elite as

an ultra-center thus is not too 'far' from

the center. Let us n o w turn to the data to

explore this further.

In T a b l e 10, this ultra-center hypothesis is tested. Five items on w h i c h we have

data both from the rank categories and

the elite are presented. For each item,

the responses of 4 ranks — 1, 3, 6 and 8

— are given together with the elite responses in ratios of positive to negative

response.

23

T h e hypothesis is clearly verified in all

five cases. If we take the average ratio

on all items, the curve drawn through the

opinion scores represented by the ratios

is quite steep: it points to the 'autocratic'

model.

M o s t of the difference between the

center category (8) and the elite is, h o w ever, due to two items — N A T O and E E C

membership. These are key foreign policy

questions in N o r w a y , in the opinion of the

elite itself. O r , more generally: Western

co-operation is the key field and very

much the policy-determining field in the

framework of Norwegian foreign p o l i c y .

It is part of the elite's role to keep this

field as 'clean' or intact as possible and to

secure as great a consensus as possible on it,

24

hence the high positive-negative ratios.

On the other questions related to foreign

aid, the differences are m u c h smaller between the elite and the rest.

We get further indication of the i m portance of these questions by comparing

the decision-makers' attitudes towards

them, with those of the elite. T h e decisionmaking b o d y within the elite m a y be seen

as an even stronger consensus-building

b o d y when it comes to the crucial foreign

policy questions. Although it is undesirable to carry the ultra-center idea too far,

we shall test the hypothesis that the

decision-makers within the elite in those

questions which the elite estimates as the

most crucial ones, constitute an ultraultra-center.

To designate the decision-maker group

we had to use subjective criteria — the

respondents' o w n evaluation of their

position within the decision-making framework. Certain objective criteria, which

will not be dealt with here, seem to give

a fairly positive validation of the subjective

judgment.

In T a b l e 11, the 5 items used in T a b l e

10 are presented together with responses

on the question of whether the respondents

agreed upon the principle that parts of

the national military forces should be

placed under U N c o m m a n d and whether

they agreed that Norwegian aid to the

developing countries should be increased.

161

160

Table

Table 12. The optimism vs. pessimism dimension: t~e .case of disarmament consequences. Ratio of optimistic

to pesstmutu: responses

II. The ultra-ultra center hypothesis: ratio of positive to negative responses

Continued NATO membership ....•.•..............•..•.•

Full EEC membership ...........•..........•.........•.

Parts of the National forces under UN command •..•...••...

Increased orwegian aid to the developing countries

.

Merchant marine assistance to the developing countries ...•..

Customs duty preferences to the developing countries ..•.....

Closer ties with: NATO/Nordic countries ..•....•...........

T h e hypothesis is again satisfactorily

verified. As expected, the distance is the

greatest on the two most crucial questions,

N A T O and the E E C . In one case — the

question of merchant marine assistance

to developing countries — there is g o o d

reason to say that rejection of the general

trend towards a higher ratio for the

decision-makers confirms the hypothesis:

the merchant marine is the most valuable

branch of Norwegian exports of goods and

services, especially in securing a fairly

favorable balance of payment. Such

considerations of this fact m a y well underlie

the attitude of the decision-makers.

Disarmament

We shall n o w proceed to the disarmament data. Several questions asked in a

national opinion survey in 1964 were included in our present study. O u r purpose

here is partly to test the projection hypothesis, partly to shed some light on the relations between 'leaders' and 'masses'

with respect to three specific dimensions,

the theoretical basis of which has been

given by Galtung. - T h e y are these: the

optimism-pessimism dimension, measured

by the respondents' expectations about

the consequences of disarmament; the

gradualism-absolutism dimension, which

gives the respondents' preference as to h o w

the disarmament process should be started

and carried out ; and the confidence versus

distrust dimension — the perceptions of or

expectations about the parties involved in

a disarmament process and their behavior.

2

5

T h e results are presented as ratios,

largely because in our study we included

Total elite

17.2

7.7

7.7

5.0

1.5

3.7

2.0

Decision-makers

31.3

15.0

15.0

6.7

0.8

4.5

7.0

a middle (ambivalent) response category

not used in the 1964 study, and this m a d e

the percentage scores as such less c o m parable. T h e questions are listed as they

appeared before the respondents (in the

opinion study in an interview guide, in

our study in a questionnaire).

On the prospects of achieving disarmament in the future, the elite is more optimistic than the general o p i n i o n . Does

this mean that the elite also is m o r e

optimistic about the international c o n sequences of disarmament? Generally we

w o u l d expect the opposite: elite persons

are less inclined to expect great results

from even important measures; international problems are not 'that easy' —

disarmament is not a panacea to those

problems. We find it difficult to present any

hypothesis on this basis. T a b l e 12, where the

data are given, in fact justifies this.

26

T a b l e 12 shows no clear tendency:

what seems to be a 'promising' trend on

the question of e c o n o m i c consequences is

broken by a contrary trend on the other

item. Perhaps the elite sees the e c o n o m i c

differences as too great to handle even if

one transfers arms expenditures to development (the logical thought in this c o n n e c tion) and even m o r e so than the other

groups; at the same time the elite sees no

contradiction between the idea that the

world will b e c o m e more stable after disarmament and the idea that conflicts m a y

still o c c u r : in fact several elite respondents

say s o ; and the score on the middle

response category on this question is 2 2 % .

Evidently we need m o r e data to clear

up the point.

A. Economic differences will disappear throughout the world

if disarmament is achieved

0.7

Economic differences will exist even if disarmament is

achieved.

B. Disarmament will create greater stability and peace-keeping possibilities in the world . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.1

Serious conflicts may arise even if disarmament is

achieved in the world.

3

6

8

Elite

0.5

0.3

0.3

0.2

1.5

0.7

0.5

1.2

N=IOOO

In Galtung's study, the hypothesis that

the center is gradualistic, the periphery

absolutistic, was relatively well established.

This gives us reason to believe that a projection, as has been made on other dimensions, is safe also in this case. O u r

hypothesis then is that degree of gradualism increases from the periphery through

the center to the elite. T h e results are

shown in T a b l e 13.

In only one case — question B — is the

projection hypothesis verified, although

the trend in the remaining two cases is

in the expected direction. T h e results on

these two items point to the 'democratic'

model presented a b o v e : the center (8)

category is extremely gradualistic, m u c h

more so than the elite. M a y this be taken

as some kind of a 'warning' to the elite

from the center that arms policies ought

not to be experimented w i t h ?

We should mention that the phrasing

of the response alternative in some in-

stances was modified or moderated in our

study, relative to that used in the opinion

study. This was done because the pre-test

showed a certain annoyance on the part

of elite respondents towards a too absolutistic content or phrasing in the alternatives. (See example in footnote to

T a b l e 13.) This 'gradualism' in the very

response alternatives m a y of course account

for some bias in the responses, making the

absolutistic (moderated) alternative more

acceptable to the elite persons. Generally,

however, such a bias is not believed to have

had any decisive influence, and it can hardly

account for the extreme center gradualism.

T h e third dimension we intend to explore is the confidence vs. distrust dimension. Galtung calls it the 'simplicity vs.

distrust d i l e m m a ' . This implies that he

combines t w o somewhat separate dimensions in o n e : first, the perception of

the disarmament process as easy or difficult (once started); second, the perception

26

Table 13. Absolutism versus gradualism: the projection hypothesis. Ratio of gradualistic to absolutistic

responses

A. We should be careful and take one step at a time ......

We should try to carry out disarmament as quickly as

possible.

B. We should start with some selected areas of the world ...

We should disarm throughout the whole world at once.

C. We should start with some weapons, for instance atomic

ones, and then take other weapons afterwards ..........

We should try to abolish all kinds of weapons at the

same time. a

I

2.0

3

1.6

6

1.8

8

5.7

Elite

2.7

0.4

0.5

0.5

0.8

1.2

2.8

2.8

4.1

18.6

5.3

aThe alternative was in our study phrased' - in a shorter time span' instead of 'at the same time'.

162

Table 14. The paMcea problem: ratro

163

of 'disann first • to 'confidence first , responses

1

We should start with disarmament to create confidence. . .. .

We should create confidence first and then disarm.

1.0

3

1.0

6

0.8

8

0.6

Elite

0.4

hypothesis, although some cases do give

support to it. T h e three dimensions explored show no clear picture either.

4.2. Differences between the elite, the opinion-

These findings lead into the remaining

three indicators used to test the confidence

versus distrust dimension. From what has

been found so far, the most reasonable

hypothesis w o u l d be that the elite is less

confident than the rank categories, between which Galtung found no clear difference ; thus we may not hypothesize any

projection in this case.

to be g o o d reason to distinguish between

the two dimensions included in the

'simplicity versus distrust' index and to

treat them separately; the data indicate

this.

T h e elite seems to be definitely more

distrustful on the question of h o w the

process should be dealt with once started

(the inspection question), while it is more

confident than the opinion categories c o n cerning to what extent the actors in the

process can be trusted (not to attack or

'cheat' the others). This perhaps reflects

the double position of the elite: on the one

hand, it is responsible for the management

of a disarmament process and has no interest in telling the world that this is an easy

task; on the other hand, the elite deals with

elites in other countries, and this tends to

create a certain possibly unconscious feeling

of solidarity: the elites of other actors are

to some extent defended against the suspicion of one's o w n public opinion. T h e

tendency is not very clear, however; on

the question of hiding weapons the elite is

also rather suspicious. Interestingly, the

elite o n c e more places itself close to the

model we have called the 'democratic'

one.

T h e hypothesis is not satisfactorily verified in T a b l e 15. We would not say that

it has been rejected, however: there seems

In general, the data presented in this

section on attitudes towards disarmament

do not support satisfactorily the projection

of relevant actors in the process as to what

extent they should be trusted or not.

Although the former may be seen as a

'technical', the latter a 'moral' aspect of

the process, the two go very m u c h together and shall be seen together in this

context as predominantly an expression

of the respondents' trust or confidence in

their international environment.

Galtung used the problem 'confidence

first, or disarmament to create confidence'

as an indicator of the degree of a panacea

perception in his study. T a b l e 14 shows to

what extent this panacea perception is

backed by the categories. Here there is a

projection trend, which was expected.

T h e conclusion drawn concerning the elite

rejection of disarmament as a panacea to

international problems is supported by the

result in T a b l e 14.

27

Table 15. The distrust versus confuIence dimension: ratro of distrust on confidence responses

A. Disarmament demands much inspection

..............

Disarmament demands little inspection.

B. All nations really want to disarm but hesitate to do so before

other nations

Some nations have acquired weapons not only to defend

themselves, but also to attack.

C. Some powers will try to hide weapons during disarmament

It is not probable that some countries will try to hide

weapons.

.....................................

1

4.3

3

3.3

6

5.0

8

4.6

Elite

10.8

1.5

0.8

0.8

1.3

0.4

3.5

1.3

1.5

2.5

1.9

maker level, and the general opinion

Contrary to the theory of foreign policy

opinion as a function of social position,

the problems which will be taken up in

this section are not based on a theoretical

framework. Thus we have no really g o o d

starting-point for examining the relations

between the three groups or levels, the

differentiation of which is not based on

any social background data, but applied

from a scheme presented by R o s e n a u . As

has already been shown, however, an exploration of data on some structural

factors makes it safe to say that the elite

stands ' o n top of the opinion-maker

sample in the system of foreign policy

communication and decision-making.

28

Furthermore, the opinion-makers (because they through active participation in

foreign policy activities to a large extent

are members of that system) are ' o n top of

the general public opinion in the pyramidal structure, which is the logical i m plication of the reasoning we n o w present.

T h e lack of a safe theoretical and

methodological basis evidently means that

we ought not carry such reasoning too far.

T w o questions will be further explored

by the use of data: First, to what extent

may one use the opinion projection idea

on the relations between the general

opinion, the opinion-makers and the

elite? Second, where is the opinion-maker

group placed in the society ? If it a bridge

between the elite and the general public,

as indicated already ? Or is it closer to the

elite by backing its opinions and thus not

filling its task, which also is to represent

the general public opinion before the

elite ?

A n d : is the opinion position of the

opinion-makers very m u c h similar to that

of the center, making them possible

partners contra the elite? From our data

on the opinion-maker sample's distribution

on the Galtung index variables, we find

that the opinion-maker sample is less

'centrist' than the elite sample; its mean

rank would probably be about 5 or 6.

T h e data which will be used cover

peace ideology and attitudes towards the

more important foreign policy questions

(cf. Tables 10 and 11) T h e peace ideology

of the three groups is presented in T a b l e

16. T h e general opinion is not really a

sample of the Norwegian population, but

is taken from a youth study which represented the population between 15 and

40 years. Twelve of the peace proposals

used in our study were included in the

youth study with much the same content

and phrasing. In the youth study, h o w ever, the proposals were presented in

questions which asked for the respondent's

approval or rejection of the proposal.

To make the two sets of data comparable

we added the two response categories

'Especially important to peace' and 'Somewhat important to peace' used in the

questionnaire in our study (cf. T a b l e 4)

Although the questions were not all

identical, and despite necessary reservations as to the operation just described,

we think it reasonable to say that the data

are comparable.

In 6 out of 12 cases the projection hypothesis holds. In one case (inter-individual relations) the trend is contrary to the hypothesis, in 4 there is a ' l o o p ' in the sense

that the youth sample is breaking or reversing the trend (Abolish hunger and

poverty, and M o r e democratic states) or

in the sense that the opinion-maker sample

is ' o n top' (Disarmament, and W o r l d

State). On the one remaining item (States

should b e c o m e more similar) the scores are

practically even.

This is not a bad result although it is

not quite satisfactory. T h e single-item

reversal of the dominant trend and the

four loops may be due to several factors.

It is perhaps especially interesting that the

164

165

Table 16. Peace ideology and the projection hypothesis.

Elite

Strengthen the U

.........•..............•

Rich countries help poor ....•...............

Abolish hunger and poverty

.

Educate the individuals to peace

.

More West contact with Eastb •..••.••.•••••••

More democratic states

.

Preserve military alliancesc

.

General and complete disarmament ........•..

Better inter-individual relations

.

.

Small countries should have more influence

States should become more similar ...........•

Establish the World State

.

96

91

90

90

89

82

80

77

61

55

52

39

% approval

Table 17. Basic foreign policy attitudes and the projection hypothesis. Ratios

Youths

Hypothesis

coniinned

89

85

85

87

60

+

+

81

70

87

Opinionmakers

87

75

60

94

84

40

83

64

79

52

48

51

47

52

71

+

+

+

+

27

a

Questions in the youth study interview guide generally started with the words 'To obtain

peace — should —'.

In the youth study, this question ran: 'To obtain peace we should have increased trade, exchange, and co-operation also between countries that are not on friendly terms.'

In the youth study, this question ran: 'To obtain peace countries should be members of mi

litary alliances so that no country or group of countries dare attack others.'

b

c

trends on the two 'sub-national' approaches — the intra- and the interindividual — are so markedly contrary

to each other. This might be explained

by an increasing group-orientation with

decreasing social position: those at the

b o t t o m of society (the periphery) place

m o r e emphasis on interaction between

individuals, because that part of life or

society — whether local, national, or international — is more meaningful and i m portant to them.

T h e opinion-maker ' l o o p ' is, in the case

of the ' W o r l d State' proposal, due to what

has already been said about the relatively

greater influx of 'idealist' or world federalist thinking a m o n g interest g r o u p

opinion-makers. T h e score on disarmament is more problematic, but is probably

explained by the relatively high percentage of 'leftists', w h o usually stress disarmament in their arms policies.

As to the relative youth preference for

'Abolish hunger and poverty' and ' M o r e

democratic states', this can be due to a

stronger impact of 'moralistic' thinking

a m o n g youth. Or youth is more occupied

with catastrophic trends, which they are

m o r e exposed to through mass media and

the world communication revolution; and

they are more truly democratic, due to

socialization of democratic values (the

elder have also been socialized to these,

but have 'forgotten' since their socialization was long ago) and possibly due to a

certain opposition toward the more central,

more influential strata (which the elite

and the opinion-makers represent).

T h e relations between the three groups

m a y also be explored by rank correlation.

T h e difference is not great; for all three

pairs it runs like this:

Elite

'Should Norway continue

in NATO, or should we

withdraw?'

'Should orway apply for

full membership in the

EEC or not?' . . . . . . . ..

'Should orway increase

its total aid to the developing countries?' .....

'If a developing country

asked for our help to

build up a merchant

marine, should we give

such help? . . . . . . . . . ..

'Should we give the devel·

oping countries customs

duty preferences on some

of their products ?'c. . ..

'Should we give our developing aid on a multilateral or bilateral basis,

primarily?' . . . . • . . . . ..

'What international organization or unit do you

think you have most in

common with/think that

Norway should establish

closer ties with?' .....

Opinion

makers

General

opinion

Acceptance

of hypothesis

ContinuefWithdraw

17.2

3.5

2.6

+

Should/Should not

7.7

5.5

2.6&

+

Should/Should not

5.0

6.0

O.lb

Should/Should not

1.5

0.7

0.7

Should/Should not

3.7

16.8

0.4

Multilat.fBilateral

3.0

1.8

1.5

+

NATO ordic

countries

2.0

1.3

0.5

+

7.1

7.0

'The UN should dispose of

parts of the national

armies to form an international peace-keeping

force' . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. Should/Should not

+

+

a

National survey, July 1967, by Norwegian Gallup A / S . N is about 1600.

National survey 1965. N= 1751

The question in the general opinion survey was 'Imagine that the best way to help a developing country would be to buy manufactured goods from it, for instance textiles, but that this

would lead to difficulties for Norwegian factories. Do you think Norway should buy such products

or not?'

From the youth study 1967; the question in this study was ' T o obtain peace we should have