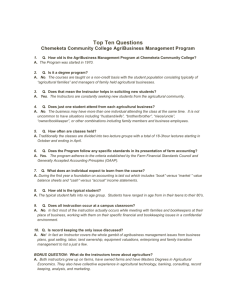

(aØr Title for the cultural Education

advertisement