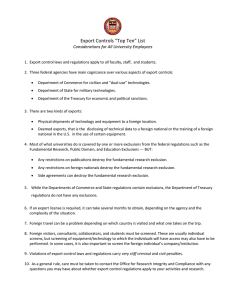

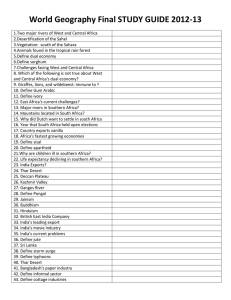

GAO

advertisement