Building the case for wellness 4 February 2008

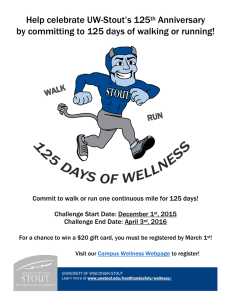

advertisement