Can Non-State Governance “Ratchet-up” Global Standards?

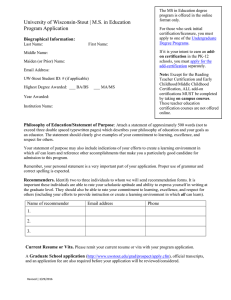

advertisement