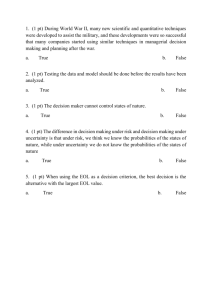

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

advertisement