The Blue Ridge Academic Health Group A call to lead:

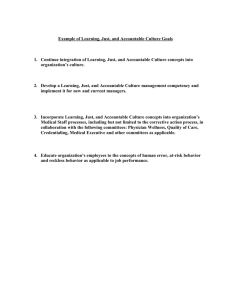

advertisement