Guide for persons involved in the development Issue Three

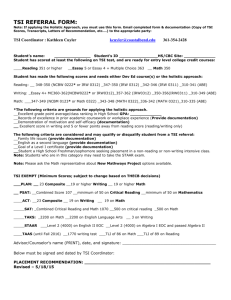

advertisement