Seedling Leaf Structure of New England

advertisement

Seedling Leaf Structure of New England

Maples (Acer) in Relation to

Light Environment

P. Mark S. Ashton, Hae Soon Yoon, Rajesh Thadani,

Graeme P. Berlyn

and

ABSTRACT.Seedlingleavesof the genusAcerfromsouthernNew Englandwere comparedin relation

to light.The species investigatedwere red maple (A. rubrumL.), a species tolerant of xericand hydric

sites; silver maple (A. saccharinum L.), a species restricted to riparian sites that are periodically

flooded; and sugar maple (A. saccharum Marsh.), a mesic species of lower slopes and valleys.

Germinatingseedlingsof all species were collectedand grownwithinfour shade treatments that had

contrastinglightquantityand quality:(1) approximately100% of full sunlight,red:far-redratio = 1.27;

(2) 40% of full sunlight,ratio= 0.97; (3) 15% of full sunlight,ratio = 0.85; and (4) 4% of full sunlight,

ratio = 0.46. Leaves, cuticles, and epidermal and palisade mesophyllcell layers were all thicker, and

stomatal densities were higher for all three species in the full sun treatment. Dimensionsof leaf

structure (leaf thickness, palisade mesophyllthickness, lowerepidermal thickness) were between 25

and 35% smaller for silver maple as compared to the other maples. Silver maple also allocated less

biomass to roots (about 15% less) and more to stems. Its thin upper surface cuticle, thin leaves, and

large leaf area predispose this species to desiccation. Phenotypic plasticity of leaf anatomical

measures was greatest for red maple, suggestingit to be more of a generalist than its congeners. Red

maple allocated greater biomass to roots in shade (17% and 27% more than sugar and silver maple

respectively),with thicker leaves and cuticle, making it least prone to desiccation. Sugar maple had

greater dry mass and total leaf area in the deepest shade than the other maples. Measures of leaf

structurecan provideusefulinsightsintoknownecologicalaffinitiesof site and shade-toleranceamong

maples. FoR.Sc•. 45(4):512-519.

Additional Key Words: Acer rubrum, A. saccharinum, A. saccharum, leaf anatomy, red:far red ratio.

Researchers

have focusedon the regenerationstageof

succession,

becauseit is a periodthatdetermines

futuretree

species

composition

formostforesttypes(Egler1954,Grubb

1977,Ashton1992).Therefore,thisstageprovidesa critical

windowof timeforunderstanding

differences

amongspecies

in anatomy,physiology,and ecology(Ashtonand Berlyn

1992, 1994). By usingmore refinedfield and greenhouse

studies,theregeneration

stagecanbeusedto examinedifferencesin shadetoleranceof closelyrelatedspecies.

T HE

MANIPULATION

OF

nFOREST

CANOPY

for

the

purpose

of alteringlightavailabilityis animportantsilviculturaltechniquefor favoringor excludingtreesof a

particularshadetolerance.Many studieshave soughtto

differentiatelightresponses

of temperatetreespeciesin order

to arrangethem into differentsuccessional

groupsfor the

purposeof silviculture(Jackson1967a,1967b,Loach1967,

1970, CarpenterandSmith1975, Bazzaz1979, Bazzazand

Carlson1982, Walters andReich 1996, Reich et al. 1998).

P. Mark S. Ashton,RajeshThadani,and Graeme P. Berlynare AssociateProfessorof Silviculture,DoctoralCandidate,and Professorof True Anatomy

and Physiologyrespectively,Schoolof Forests,and EnvironmentalStudies, Yale University,New Haven, Connecticut06511. Hae Soon Yoon •s

Professorof Biology,Departmentof Biology,Dong-A

University,

Pusan604-714, Korea.Authortowhomcorrespondence

shouldbe addressedis Mark

S. Ashton.

hone: (203) 432-9835; Fax: (203) 432-3809; E-maihmark.ashton@yale.edu.

Acknowledgments:

The studywas donewhileHae SoonYoonwas on sabbaticalat Yale University.Shewouldliketo thank Dong-AUniversity,Pusan,

Koreafor the fellowshipthat made this studypossible.We wouldalso like to acknowledgethe logistichelp receivedfrom SarojSivaramakdshnan

and lliana Ayala,

ManuscriptreceivedAugust17, 1998. AcceptedApril15, 1999.

512

ForestSctence

45(4)1999

Copyright¸ 1999 by the Societyof AmericanForesters

Formaples(Acerspp.),fieldstudies

havefocused

oncomparisons

between

canopy

andunderstory

species

in relationto

forestmicroenvironments

(Lei andLechowicz1990,Sipeand

Bazzaz1994,1995).Lei andLechowicz

(1990)studied

saplings

of co-occurring

maplespecies,

in a mesicnorthern

hardwood

forestin Quebec,

Canada.

Theunderstory

species

in theirstudy,

stripedmaple(A.pennsylvanicurn

L.) andmountain

maple(A.

sptcaturn

Lam.), had characteristics

(largeleaf area,planar

architecture)

thatmadethemmoreshade-adapted

thansugar

maple(A.saccharurn

Marsh.).Amongeightmaplespecies

from

AsiaandNorthAmerica,LeiandLechowicz

(1997,1998)found

differences

in photosynthesis

andwater-use

betweencanopy

andunderstory

species

andbetweenthosespecies

knownto be

light-demanding

versus

thosethatareshade-tolerant.

Similarly,

SlpeandBazzaz(1994,1995)showedA.

rubrumL. (redmaple)

survived

in a widerrangeof lightenvironments

ascompared

to

sugarandstripedmaple.All thesestudies

haveprovidednew

insightintoourunderstanding

of linkages

betweentheecology

andphysiology

of trees.

The objectiveof our studywas to build on this work by

examiningrelationships

betweenattributesof leaf structure

and the ecologicalsite affinitiesof threemaplespecies.

Certain attributesof leaf structure(i.e., cuticle thickness,

palisademesophylllayer thickness,stomataldensity)may

provideinsightinto someof the underlyingmechanisms

affectingthe shadetoleranceand site affinitiesamongred,

sugar,andsilvermaple(A. saccharinurn,

L.). We hypothesizethat speciesrankingsof leaf structureattributeswill

changeacrossthelight treatments

in a directionconsistent

with the knownsite affinity of the species.Basedon the

literature,

wewouldalsoexpectmaplespecies

thathavebeen

recorded

tobemoresitegeneralist

(i.e.,redmaple)toexhibit

greaterplasticityin leaf structure

betweenthebrightest

and

darkestshadetreatments

ascomparedto maplespeciesthat

areconsidered

sitespecialists

(i.e., sugarmaple).

The speciesselectedfor our studyall occurwithin the

mixed-deciduous

forestof southern

New England,buteach

species

appears

restricted

moreorlesstodifferentsiteconditions(BurnsandHonkala1990).Redmapleis a lightgenerahstthat growswell in shadeand sun.Red mapleis also

tolerantof shallowsoilsof uplands

thatareseasonally

xeric,

andalsohydricsoilsthatareseasonally

anaerobic,

although

ecotypic

differences

in physiology

andgrowthappearnotto

exist (Will et al. 1995). Sugarmaple is a shade-tolerant

species

thatoccupies

thelowertoe-slopes

withdeepsoilsthat

are mesicyear round.The third species,silver maple,is

considered

light-demanding

andisrestricted

to floodedalluvialsoilsthatareadjacent

tomovingwaters.It canbeplanted

andgrownon well-drainedsites,but seldom,if ever,reproducesthere(Gabriel 1990).

Materials

and Methods

Shade Treatments

Eightshelters

wereerected(1 x 1x 2.5m woodenframes)

andplacedonbenches

withina greenhouse

at YaleUniversity.We alteredlightquality(R.'FRratio)andphotosynthetically activeradiation(PAR, 400-700 nm) to createfour

treatments

(twoshelters

pertreatment)

thatsimulated

arange

offorestlightenvironments.

TheR:FRratiowasmeasured

as

theratioof quantumirradiancebetweenthewavebands

655665 nm and 725-735 nm (Lee 1985, Lee et al. 1996).

Treatments were based on measurements made across forest

openings

onridgeandvalleysitesat theYale-MyersForest

in thenortheastern

uplands

of Connecticut

(41ø57'N; 72o07

'

W) (AshtonandLarson1996).Thisforesttypeis dominated

byanoak-hickory

canopy,

witha subcanopy

ofredmapleand

sugarmaple(Westveld

etal. 1956).Compared

withamature

northernhardwoodforest,wheremaplespeciesoftendominatethecanopy,understory

R:FR ratiosof theoak-hickory

foresttypeareconsiderably

higher(R:FRratioof 0.47versus

0.25),because

of moreopenconditions

withproportionately

fewerstoriesof shade-tolerant

treesbelowtheforestcanopy

(Canhamet al. 1990).

Thequalityandamountof lightfor threeof thetreatments

was alteredby sprayinga ratio of selectedpaintpigments

mixedin a varnishbaseontoclearplastic(Lee 1985,Ashton

andBerlyn1994).Quantumsensors

andthermocouples

(LI190 SZ, 190 SA, LI-1000-16, LI-COR, Lincoln, Nebraska)

were usedto obtainan estimateof daily PAR anddiurnal

temperature

variation.Measurements

weremadeevery 10 s

on severalsunnydaysat the beginningof the experiment

(June1994).Lightandtemperature

sensors

werepositioned

horizontally15 cm abovethegreenhouse

benchandwithin

the shelters. Ten minute means for each shelter were calcu-

latedbasedonthe 10 sreadings.Thesemeansweresimultaneouslyrecordedfrom sunriseto sunset(approximately15

hr) usinga datalogger(LiCor 1000).

Shadetreatmentsprovidedseedlingswith 4%, 15%,

40%, and100%of sunlight,basedondallyestimated

totalsof

PAR received(seeTable 1 for details).It shouldbenotedthat

the 100% treatment is less than incident PAR because of

somereflectionfrom the greenhouse.

Germinatingseedof redmaplewerecollectedduringthe

last2 wk of May 1994fromatleastfourdifferentparenttrees

in separate

locationswithin the Yale-MyersForest,Union,

Connecticut.All seedlingscollectedwere at the earliest

stagesof cotyledonexpansion,andnoneexhibitedany ob-

servable

leafinitiation.Germinating

seedlings

ofsilvermaple

of a similardevelopmental

stagewere collectedat four

separate

locationsalongthebanksof theQuinipiacriver in

Tabla 1. Light traatmants; PAR--photosynthatic activa radiation as a maasura of amount of light; R:FR--rad to far

red ratio of light as a measura of light quality.

Full sun(100%)

Diffuseshade(40% sunlight)

Brightunderstory(15% sunlight)

Darkunderstory

(4% sunlight)

PAR

MaximumPAR

Maximumtemp

R:FRratio

(molsm-2d-l)

(pmols

m-2s-l)

('C)

1.27

36.62

1,600

32

0.97

0.85

0.46

14.65

5.31

1.50

700

300

60

30

30

29

Forest

Sctence

45(4)1999 513

Hamden,Connecticut,

duringthe lastweek of May 1994.

Sugarmapleseeds

thathadbeendispersed

theprevious

fall

werecollected

in thesamemannerasredmapleattheYaleMyers forestduringthe secondweek of May 1994.Each

younggerminantwasimmediatelyplantedintoa plasticpot

(15 cm depth,10 cm diameter)that containedPromix(a

mixtureof sphagnum

moss,perlite,vermiculite,dolomite

andcalcitelimestone,and wettingagent,PremierBrands,

Inc.,Quebec,Canada).

A smallamountof foresttopsoilfrom

the seedlingcollectionsiteswasaddedto eachpot at the

beginning

of theexperiment

to ensurea sourceof vesiculararbuscular

mycorrhizae

(VAM) innoculum

for theseedling

roots.Fivepotsfor eachspecies

wererandomlyassigned

to

positions

withina shelter.All germinating

seedwasplaced

withintheshelters

beforeshootextension

to ensureproper

exposure

to thetreatments

duringleaf expansion

anddevelopment.To ensureagainstpossible

environmental

variations

in differentpartsof the greenhouse,

the positionof each

shelterwasrotatedmonthlyandwateringwasregulatedto

maintainthePromixat fieldcapacity.A standard

strengthof

Miracle-Gro,an NPK fertilizer (15-30-15), was addedat

monthlyintervals.

The seedlings

weregrownwithintheselight treatments

foratleastfourmonths(June1-September

30, 1994).At the

endof thisperiod,all seedlings

weremeasured

for height,

root collar diameter,and leaf area. Seedlingswere then

harvestedandrootswashedfree of soil,thenroots,stem,and

leaveswereseparated

anddriedfor 48 hr at 80øCfor determi-

nationof dryweights.Leafdryweightsincludedbothlamina

andpetiole.

AnatomyMeasurements

Foreachspecies,

a singleleaffromfiveseparate

seedlings

wererandomlychosenwithin sheltersfor eachshadetreatment.Onlyundamaged,

fullyexpanded

leaveswereselected.

To determinestomatadensity,stomataaperturelength,

andepidermalcelldensityleaf sections

(1 x 1 cm)weretaken

fromthesampleleafin themiddleportionof thelamina.Each

sectionwasincubated

in a 50øCovenin 5% sodiumhydroxideto clearleafpigments.

Sections

werethenstainedwith 12 dropsof 0.5% aqueous

toluidinebluesolutionandmounted

in Karolightcornsyrupona viewingslide.Foreachsection,

thetotalnumberof stomata

andepidermal

cellswerecounted

and three stomaaperturelengthswere measuredfor five

fields of view on the abaxial side of the leaf. No stomata were

observed on the adaxial leaf surfaces.

For cross-sections,

another1 x 0.5 cm piecewastaken

acrossthemidrib, adjacentto the sectionusedfor stomata

and epidermal measurement.This sectionwas cut into

threethinstripsof aboutI x 0.2 cmandimmediatelyfixed

in cold FAA (formalin:aceticacid: alcohol).The strips

weredehydratedin a tertiarybutyl alcoholseriesandthen

embeddedin separatewax blocks(Berlyn and Miksche

1976). Cross-sections

werecut of eachstripat 12 gxnwith

a cryotomeand mountedon a slide. The tissuewas then

stainedwith safraninandfastgreen(Berlyn andMiksche

1976). For each of the three slides, three measurements

weremadeof leaf thickness,

cuticlethickness

of theupper

leaf surface,upperandlowerepidermalcell thickness,and

spongyand palisadecell layer thickness.Each slide was

measuredin different positionsthat avoided the midrib

region.Threeleaf sectionsweremeasuredfor eachsingle

leaf selectedfrom eachof five seedlingsper speciesand

shade treatment. Measurements

of cell dimensions were

madeusinga 12.5 x filar micrometereye-pieceandsintable objectivesfor the variousmeasurements.

Statistics

We investigateddifferencesin leaf anatomyusingan

analysisof variance(SAS 1990) for a split-plotexperimental design where shadetreatments(two replicates)

were the main plots and tree specieswere subplots.For

eachmeasure,we testedfor main differencesamongshade

treatments;subplotdifferencesamongspecies;and for

interactionsamongspeciesand shadetreatments(Table

2). Whereshadetreatments

werepooled,differencesamong

specieswere analyzedat the 5% significancelevel using

Fisher's PLSD post hoc test. Responsecurve analys•s

using orthogonalpolynomialcontrastswere carried out

for each speciesacrossthe shadetreatments(4%, 15%,

40%, and 100% of full sunlight).Contrastscompared

relationships

betweenthe variousleaf structuremeasurements and light levels using both linear and quadratic

constraints(Table 2). We usedboth linear and quadratic

constraints

to examinewhetherspeciesexhibiteddifferent

contrastrelationships.

For a measure of the variation in anatomical attributes we

usedan indexof phenotypicplasticity(P = [1-(x/X)]) that

includedcomparisons

betweenmeanvaluesfor the darkest

(x) andbrightest(X) shadetreatments.

To obtaina relatave

comparison

amongspecies

of theamountof stomata

areaper

unit areaof leaf we usedthe productof stomataaperture

Table 2. F-valuesfor analysesof varianceof variousanatomicaland growth measuresusinga split-plotdesignwhere shadetreatments

were the main treatments and the subplots were species.Variable codes are: LT--leaf thickness;CT--cuticle thickness;UE--upper

epidermis;PM--palisade mesophyll;LE--Iower epidermis;EP--upper epidermal density; SF--stomatal frequency; DW--dry weight;

HT-- height;RC-- root collardiameter;SLA- specificleafarea;TLA--total leaf area;LMR--leafmass ratio;SMR--stem massratio;RMR-root mass ratio. Levels of significance: P< 0.05, *; P< 0.01, **; P< 0.001, ***

Shade

Residual

df

3

4

Species 2

LT

10.1'*

CT

3.6*

UE

6.5*

PM

19.3'**

LE

4.8*

EP

1.4ns

SF

DW

2.4ns 62.5***

HT

75.1'**

RC

111.4'**

SLA

4.2*

TLA

60.1'**

LMR

SMR

1.6ns 1.3ns

RMR

2.0ns

23.8*** 2.4ns 26.4***

30.8***

11.3'*

5.74*

2.35ns 26.5***

83.8***

46.4***

3.4ns

15.6'*

2.2ns

2.4ns

3.5*

0.9ns 0.9ns 0.9ns

1.9ns

0.9ns

0.6ns

10.2'*

13.8'**

3.1ns

4.5ns

0.9ns

1.0ns

1.0ns

Shade x

species 6

Subplot

residual 8

Error

23

514

Forest

Sctence

45(4)1999

l.lns

5.8ns

lengthandstomata

density,andcalledit stomata

areaindex

(SAI) (AshtonandBerlyn1994).We alsousedSalisbury's

stomatal

indexwhichistheratioof guardcellnumberto total

epidermalcell number(excludingguard cells) to better

understand

howstomata

densityisinfluencedbylightduring

leafdevelopment

(Salisbury1928).

Results

Leaf Anatomy

Analysesshowedthat differencesamongleaf samples

taken from the samespeciesand within the samelight

treatmentwerenot significantly

differentfromeachother.

Comparisons

amongspecies,

andamonglighttreatments,

all

showedhighly significantF values(? < 0.01) (Table 2).

Interestingly,interactions

betweenspeciesand light treatmentwere not significant,suggesting

that speciesdid not

changerankin relationto eachotheracrosslight levelsfor

anyof the anatomicalmeasures.

Leaf thickness

andupperepidermal,palisademesophyll

and lower epidermallayerswere greatestfor red maple.

Cuticle thicknesswas an exceptionwhere red and sugar

maplehadthe samethicknesses.

Thicknesses

for almostall

attributesmeasured,exceptfor the upperepidermallayer

thickness,

wereleastfor silvermaple(Table3).

Phenotypicplasticity(P) of leaf blade,and upperand

lowerepidermallayerthicknesses,

wasgreaterforredmaple

ascompared

totheothermaples(Table3). Bothredandsugar

maple,however,hadgreaterplasticitiesof cuticleandpalisademesophyllthicknesses

thansilvermaple.

For all species,leaf thicknessexhibitedeffectsin contrast that were significantwith increasein light levels.

Contrastsshowedapproximatelymonotonicupwardsloping relationshipsas leaf thicknessincreasedwith light

Tabla3. F-valuesfor responsecurveanalysescomparingmaasuresof tha variousleaf attributasacrossthe four light treatmantsusing

linaar and quadraticcontrasts(laveIsof significanceP< 0.05, *; P< 0.01'*). Maans ara givan with standarderrorsin paranthesasfor the

various leaf anatomical attributes for aach light traatment and for all traatments combined. Fishar'sPLSDtast (P < 0.05) was usad to

comparepooledmaansof aachspecies[lattersdenotedifferencesamongspacies(A> B> C)].P= Plasticity[1 (x/X)] whare xis tha value

in 4% sunlightand Xis the valuain 100%sunlight.

Comparisons

amongspecies

Contrasts

(means

over

Linear Quadratic all treatments)

4%

Comparisons

among

treatments

foreachspecies

15%

40%

100%

P

Leaf thickness(gm)

A. rubrum

A. saccharinum

A. saccharum

15.49'*

25.47**

8.56**

26.12'*

10.07'

4.13ns

93.36(2.68)A

67.83(1.83)C

81.90(2.88)B

77.39(3.20)

59.19(2.48)

71.79(5.35)

84.98(2.82)

62.74(2.89)

71.81(3.46)

98.83(2.57)

73.89(2.79)

87.63(4.53)

108.92(5.14)

72.61(3.72)

90.76(6.11)

0.29(0.03)

0.20(0.02)

0.20(0.03)

2.56 (0.14)

2.29 (0.06)

2.16 (0.10)

2.33(0.44)

2.37 (0.14)

2.59 (0.13)

2.63 (0.46)

2.52 (0.13)

2.51 (0.24)

3.10(0.22)

2.42 (0.17)

2.96 (0.30)

0.24(0.02)

0.09(0.01)

0.27 (0.03)

15.33(0.49)A

11.77(0.36)B

11.71(0.32)B

12.87(0.74)

10.64(0.95)

11.12(0.29)

14.60(0.98)

11.13(0.62)

11.31(0.45)

16.34(0.69)

12.89(0.70)

12.27(0.70)

17.04(0.99)

12.04(0.61)

11.85(0.73)

0.24(0.05)

0.16(0.02)

0.09(0.02)

40.65(1.62)A

27.58(1.02)C

32.78(1.85)B

29.99(1.34)

22.27(1.67)

25.64(2.70)

37.66(1.31)

24.87(1.04)

25.17(1.97)

44.49(2.04)

30.53(1.49)

36.58(2.18)

48.56(2.04)

30.88(2.25)

39.70(4.09)

0.38(0.06)

0.27(0.03)

0.37(0.03)

11.91(0.40)A

9.63(0.30)C

10.25(0.24)B

12.16(0.83)

8.86(0.34)

10.61(0.42)

10.30(0.56)

8.81(0.40)

9.47(0.40)

11.41(0.69)

10.11(0.80)

10.26(0.43)

13.69(0.76)

10.50(0.49)

10.72(0.54)

0.25(0.03)

0.15(0.02)

0.11(0.03)

3,092(105)B

4,226(101)A

3,999(165)A

3,168(72)

3,996(93)

4,158(148)

3,188(131)

4,628(97)

3,484(175)

2,685(114)

4,025(150)

3,576(146)

3,326(103) 0.19(0.03)

4,254(64)

0.13(0.03)

4,781(192) 0.27(0.04)

460 (11.9)B

516(12.3)A

406 (16.4)C

385 (11.6)

420 (6.1)

378 (17.6)

471 (10.0)

573(13.3)

339 (9.3)

439 (13.0)

576(16.4)

364 (7.9)

545 (13.1)

498(12.4)

543 (32.0)

0.29(0.03)

0.26(0.03)

0.38(0.05)

12.5(0.25)

10.6(0.22)

10.4(0.27)

13.0(0.22)

9.7 (0.26)

12.2(0.44)

14.4(0.30)

7.7 (0.11)

8.0 (0.26)

0.12(0.02)

0.27(0.03)

0.35(0.04)

Cuticlethickness

(gm)

A. rubrum

A. saccharinum

A. saccharum

7.19'

1.71ns

0.31 ns

62.49**

0.34ns

5.77*

2.67 (0.09)A

2.41 (0.06)B

2.61 (0.12)AB

Upperepidermallayerthickness

(gm)

A. rubrum

`4. saccharinum

`4. saccharum

16.14'*

3.95*

1.10ns

17.14'*

0.95ns

0.10ns

Pahsade

mesophyll

layerthickness

(gm)

`4. rubrum

`4, saccharinum

`4. saccharum

11.76'*

13.47'*

4.83ns

17.52'*

6.72*

2.88ns

Lowerepidermal

layerthickness

(gm)

`4. rubrum

`4. saccharinum

0.00ns

11.30'*

3.64ns

10.87'*

•4. saccharum

0.04ns

0.00ns

Epidermal

celldensity

(number/ram

2)

`4. rubrum

.4. saccharinum

.4. saccharum

0.47ns

2.59ns

1.14ns

0.28ns

0.25ns

6.58*

Stomata

density

(namber/mm

2)

.4. rubrum

.4. saccharinum

.4. saccharum

1.07ns

0.12ns

0.00ns

33.09***

0.05ns

2.20ns

Stomaaperture

length(gm)

.4. rubrum

0.45ns

0.89ns

.4. saccharinum

.4. saccharum

0.00ns

3.02ns

1.13ns

3.63ns

13.13(0.23)A

12.5(0.16)

9.30(0.17)B

9.2 (0.09)

10.13(0.27)B

9.9 (0.12)

Stomata

areaindex(number/mm

2* aperture

length)

.4.rubrum

1.91ns 18.83'

6,040(131)A

4,812(103)

.4.saccharinum 2.24ns 0.76ns 4,799(101)B

3,864(44)

.4.saccharum 0.49ns 0.07ns 4,113(138)C

3,742(108)

Stomatal

index(guardcellnumber/epidermal

cellnumber)

.4. rubrum

0.25ns 0.35ns

.4. saccharinum

.4. saccharum

5.52ns

0.24ns

0.01ns

0.09ns

5,887(121)

5,707(164)

7,848(176) 0.39(0.05)

6,074(130)

3,526(100)

5,587(153)

4,441(128)

3,835(75)

4,344(198)

0.297(0.030)A 0.243 (0.026)

0.244(0.023)AB 0.210(0.018)

0.295(0.031)

0.276(0.022)

0.327(0.036)

0.286(0.032)

0.328(0.027} 0.26 (0.03)

0.234(0.012) 0.27(0.04)

0.203(0.034)B 0.182(0.041)

0.195(0.038)

0.203(0.031)

0.227(0.049) 0.20(0.03)

0.38 (0.06)

0.21(0.06)

ForestSctence

45(4)1999 515

Whole-Plant Size

level, with linear constraintsshowinglevels of significancefor all species,and quadraticconstraintsshowing

significancefor red andsilvermaplesonly (Table 3).

Increases

in cuticlethickness

showedsignificanteffectsin

quadraticcontrast

withanincreasein lightlevelsfor redand

sugarmaplebutnotfor silvermaple.Linearcontrasteffects

wereonlysignificant

across

lightlevelsforredmaplecuticle

thickness.Upper epidermallayer thicknessalsoincreased

with an increasein light levels but this contrastwas only

significantfor redmapleandto a lesserdegreesilvermaple

(linear contrast).Increasesin palisadethicknessshowed

significantcontrasteffectswith increasein light levelsfor

bothredandsilvermaple.Onlysilvermapleshowedsignificantcontrasteffectsfor lowerepidermis.

With theexception

of thequadratic

contrast

forredmaple,

nosignificant

effectswereshownbetweenstomata

aperture

lengthor stomatadensityandincreasinglight levels(Table

3). Stomatadensitywasgreatestfor all treatmentsin silver

maple,followedin decliningorderby red mapleandsugar

maple(Table3). Stomataaperturelengthwasgreatest,but

plasticitywas lowest for all treatmentsin red maple as

comparedto silverandsugarmaple.The smallestaperture

lengthsfor silverandsugarmaplewere in the 100%treatment.However,redmaplehadthe largeststomataaperture

lengthatthislightlevel.Sugarmaplewasthemostplasticfor

stomatadensityandaperturelength.

Stomataareaindex(SAD indicatedredmapleto havethe

highestrelativestomataarea,followedin decliningorderby

silvermapleandsugarmaple.SAI plasticitywasalsohighest

in redmaplefollowedby silvermapleandthensugarmaple

(Table 3). Salisbury'sstomataindex demonstrated

similar

trends(Table 3).

Contrastsusinglight levelsagainstvariousmeasuresof

leaf size andarea,andthe variousmeasures

of plantsize

(height,rootcollardiameter,drymass)all showedsigmficantlinearandquadraticeffects,exceptfor ratio between

leaf areaandleaf mass(specificleaf area;SLA) (Table 4).

Specificleaf areawashighestfor all threespeciesin the

4% treatment and lowest in the 100% treatment, but

contrastswereonly significantfor silvermaple(Table4)

Thoughthe samegeneraltrendwasevidentfor all species,

relativedifferencesbetweenhigh andlow light treatments

were greatestfor red maple.Total leaf area per seedhng

wasgreatestfor the 100% treatmentandlowestfor the4%

treatment. In the 100 %treatment, the individual leaves are

thereforesmallerin area,but therewere sufficientlymore

leavessothattheoverallleaf areaof theplantswasgreater

Relative differences in total leaf area between the 4% and

100% treatmentswere greatest in both silver and red

maple as comparedto sugarmaple. In addition, they had

largertotal leaf areasper seedlingthansugarmaplein all

but the 4% treatment(Table 4).

All sizemeasurements,

namelyheight,diameterof root

collar,andtotaldry massof seedlings,werehighestin the

100%treatmentfor all species,andweregenerallylowest

in the 4% shadetreatment.Measuresof height and root

collarshowedsignificantinteractionbetweenspeciesand

light treatmentsindicatingthat specieschangedrank m

relationto eachotheracrossthe differentlight treatments.

In all cases,greatestdifferencesamongtreatmentswere

shownin silver and red maple (Table 4). Silver maple

allocatedproportionatelylessamountof biomassto roots

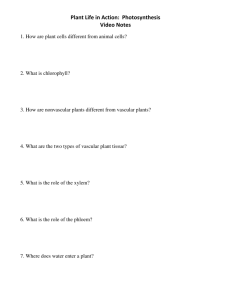

as comparedto the othermaple species(Figure 1).

Tabla 4. F-valuesfor response curve analyses comparing maasuras of growth acrosstha four light treatments using linaar and quadratic

contrasts(levalsof significanceP< 0.05, *; P < 0.01**). Meansare givenwith standarderrorsin parenthasasforthe variousleafanatomical

attributas for each light treatmant and for all treatments combined. Fisher's PLSDtast (P < 0.05) was usad to compare pooled means

of each species[letters denota diffarencesamong species(A > B > C)]. P = Plasticity[1 - (x / X)] where x is the value in 4% sunlightand

X is tha valua in 100% sunlight.

Comparisons

among

Contrasts

treamaents

for

Linear

Quadratic eachspecies

Height (cm)

d. rubrum

22.2**

d. saccharinurn63.5***

A. saccharum 4.41ns

Rootcollar diameter(mm)

d. rubrum

75.9***

d. saccharinurn76.7***

d. saccharurn 29.22**

Total dry mass(g)

d. rubrum

19.1'

d. saccharinurn35.0***

d. saccharum 12.6'*

4%

Comparisons

amongspecies

(meansoverall treatments)

15%

40%

100%

P

22.16 (1.26)B

28.97 (1.87)A

13.63(0.81)C

9.99 (0.75)

11.75(1.51)

10.53(1.11)

19.36(2.01)

26.14 (2.25)

10.51(0.98)

26.94(1.71)

36.51 (2.56)

14.82(1.75)

30.46(2.06)

41.49 (2.38)

17.47(1.60)

0.67 (0.06)

0.71 (0.06)

0.41 (0.05)

111.0'**

57.0***

73.8***

4.46 (0.22)A

3.52 (0.20)B

3.09 (0.15)B

2.18 (0.15)

1.61(0.08)

2.73 (0.16)

3.90 (0.26)

3.17 (0.28)

2.28 (0.10)

5.41 (0.27)

4.52 (0.28)

3.16 (0.20)

6.01 (0.38)

4.80 (0.26)

3.94 (0.39)

0.64 (0.06)

0.66 (0.05)

0.32 (0.04)

27.6**

34.5***

22.1'*

2.49 (0.25)A

1.84(0.23)B

1.10(0.12)C

0.42 (0.07)

0.13 (0.02)

0.69 (0.16)

1.47(0.24)

1.15(0.23)

0.52 (0.06)

3.32 (0.32)

2.68 (0.44)

1.24(0.21)

4.45 (0.50)

3.41 (0.42)

1.78(0.30)

0.90 (0.08)

0.97 (0.07)

0.61 (0.06)

3.82ns

42.16'*

1.75ns

3.96 (0.16)B

4.48 (0.26)A

4.08 (0.37)B

7.76 (0.46)

6.21 (0.36)

6.80 (0.70)

3.04 (0.09)

4.81 (0.21)

3.63 (0.37)

2.63 (0.09)

3.75 (0.24)

3.38 (0.68)

2.39 (0.13)

3.17 (0.22)

2.53 (0.16)

0.69 (0.06)

0.49 (0.05)

0.64 (0.07)

32.1'**

78.15'**

5.86*

Specific

leafarea(SLA;cm2/g)

d. rubrum

2.94ns

d. saccharinurn39.10'*

d. saccharum 0.12ns

Totalleafarea(cm2)

d. rubrum

30.44*

d. saccharinurn29.21'

14.65'

13.25'

199.42(19.09)B

250.01 (29.54)A

d. saccharurn 27.05*

17.32'

103.17(22.13)C 52.1(12.4)

516

ForestSctence

45(4)1999

38.6 (6.6)

34.7 (6.1)

175.4(24.9)

230.7 (30.2)

281.1 (13.8)

374.3 (51.7)

302.7 (30.9)

360.3 (30.3)

0.87 (0.11)

0.90 (0.08)

64.8(15.0)

140.3(33.0)

155.4(28.1)

0.67(0.07)

A.rubrum

A.sacchartnum

A.saccharum

[]

Leaves

[]

Stem

ß

Roots

to differinglight regimesare consistent

with the broad

distribution

of redmaple,ascompared

to theothermaple

species

in thisstudy.Thismaygiveredmaplea competitive

advantage

wherewaterislimitingandinmoreopen,desiccatingenvironments

(Will et al. 1995,Canhamet al. 1996).

Silvermaplegrowsalongstreams,

ponds,

lakesandrivers.

It growslargest

in rivervalleysonwet,poorlydrained

soils.

It isa medium-lived

tree(125-150yr)thatisshade

intolerant

(Gabriel 1990), andit can withstandseveralweeksof flood-

ing(Hosner

1960).Although

it iswidelyplanted

inyards

and

Percentage PPFD of the abada treatment•

Figure1. Proportionalallocationof dry massto roots,stem,and

leavesamongthelighttreatments

foreachofthespecies.

Light

treatment was measured as a percentage of the total

photosynthetic

photonflux density(PPFD)recordedin the full

sun treatment.

Discussion

Whenleafanatomical

measures

aretakenseparately,

they

did not changerank acrosslight levelsfor the different

species,

suggesting

thatrelationships

among

maplespecies

remained

consistent.

However,

comparing

measures

of leaf

anatomy

withgrossmeasures

of plantsize,maplespecies

showed

separate

relationships

different

fromeachother.Our

studyof leafstructure

variation

in relationto changes

in

whole-plant

sizesupports

evidence

thatmaplespecies

ofthe

southern

New Englandforestshavesite affinitiesthatare

bothdistinctyetoverlapping

in relationto eachotherwith

regardto availability

of lightandsoilwater.The study

showed

howleafanatomical

andplantsizeattributes

of the

threemaplespecies

aresuited

tothedifferent

habitats

they

occupy

ontheforestlandscape

fromstreamsides

tohilltops.

Inthenextfewparagraphs,

wediscuss

relationships

between

leafstructure,

measures

ofplantsize,andsiteaffinitysepa-

parks,it seldomregenerates

in thesesituations

dueto insufficientlight andwater(Gabriel1990).The thinnerdimensionsin leafstructure,

low proportional

allocation

to roots,

greaterheight growth,and smallerroot collar diameters

indicatethatsilvermaplewouldgrowfaster,relativeto the

othermaplesin highlightenvironments

wheresoilwaterwas

plentiful.

Incontrast

toredmaple,silvermaplegrows

talland

thin seedlings,

a growthhabit that wouldbe suitablefor

nutrient-rich

andever-moist

soilsof floodplains,andwhere

competitionfor light, ratherthan soil water, is the most

limiting factor. This is consistentwith resultsfrom other

studiesthatcompared

heightgrowthof shade-intolerants

withshade-tolerants;

shade-intolerants

havegreater

height

growththanshade-tolerants

evenin low lightconditions

(Loach1970•treatments

providing

3 and17%sunlight;

Walterset al., 1993a,b•treatment

providing15-20%sunlight;WaltersandReich1996--treatment

providing

8%).

However,

inverylowlightconditions

(e.g.,2%)Waltersand

Reich(1996)foundshade-intolerant

species

grewslower

thanshade-tolerants;

butwedidnotfindthisforour4%light

treatment.

Also,thelowerlevelsof responsiveness

thatwe

observed

in silvermaple,relativetoredmaple,in almostall

dimensions

ofleafstructure

(leafthickness,

cuticle,

palisdae

mesophyll,

upperandlowerepidermal

layers)isalsoconsistent with silver maple'srestrictionto certainsites.Our

findings

on theleafstructure

of silvermaplecorroborate

ecological

observations

thatit isalight-demanding

specialist

ratelyfor eachspecies.

requiring

moistsoilsandthefull sunof largecanopy

openRedmaple

grows

inalmost

two-thirds

ofthe88nontropi- ings.Unlikeredandsugarmaple,thereis no supporting

calforestcovertypesin eastern

NorthAmerica(Waltersand

literature

onthefunctional

properties

of silvermaple.

Yawney1990).It formsredmapleswamps

andoccurs

on

Sugarmaplegrowsin 24 forestcovertypesof eastern

drought-prone

hilltopsintheregion;

it maygrowinassocia- NorthAmericaandisa majorcomponent

in 7 (Godman

etal.

tionwithbothsugarandsilvermaple.It isconsidered

shade

1990).It isfairlylong-lived

(250-400yr)andoneofthemost

tolerantandgrowsfromsealevelto 2000m (Waltersand

shadetolerantmaplespecies.

It is restricted

to well-drained

Yawney1990,Harlowet al. 1991).Red maplehadthe

soilsanddoesnotoccur

in swamps

orsitesthatareperiodithickest

leavesunderall lighttreatments.

Thisthickness

was

callyinundated.

It alsodoesnottolerate

dry,shallow

soils.It

manifested

in allcelllayers

measured,

viz.epidermis,

paligrowsathighelevation

in thesouthern

Appalachians

(2,000

sademesophyll,

andcuticle.

Redmaplehadthegreatest

root

m), whereas

in NewEnglandit isseldomseenabove1,000m

collardiameter

for all lighttreatments

ascompared

to the

(Godman

etal. 1990).Theleafstructure

ofsugar

maple

is,in

most cases,intermediate in measureddimensionsbetween

other

species.

In thelowlighttreatment

(4%)redmaple

had

a highproportion

ofitsdrymass

allocated

toroots(54%and

redmaple

andsilvermaple.

Thehighdimensional

changes

of

30%greater

allocation

ascompared

tosugar

andsilver

maple sugar

maplepalisade

mesophyll

thicknesses

across

thelight

respectively),

supporting

similarfindingsof studies

donein

treatments

suggests

an abilityof sugarmapleto adaptto

shade

houses

(Gottschalk,

1994,Groninger

etal. 1996)and

varied

lightenvironments.

Thisisbecause

thepalisade

mesotheforestunderstory

(SipeandBazzaz1994,DeLuciaetal.

phylllayerisanimportant

siteforlightcapture

andphotosyn1998).Thismorphological

traitmayprovide

structural

bulk

thesis.

Sugar

maplehada greater

totaldrymass

(39%more),

andconsiderable

space

forcarbohydrate

andwaterstorage. rootcollardiameter(20%more),andtotalleaf area(26%

All these

attributes

andtheirhigher

levelsofresponsiveness more)inthelowlighttreatment

ascompared

toredmaple,

the

ForestSctence

45(4)1999 517

next highest.The lowerproportionalallocationto rootsof

sugarmaple(30% less)in low lightsuggests

it mightbemore

susceptible

to soil moisturestressthan red maple.Also,

becausemeasuresof plantsize acrossthe light treatments

weresmallerfor sugarmaple(height-63%less;rootcollar

diameter-50%less;totalleaf area-22%less;anddrymass32% less)thanthe othermaples,we suggest

thatit is less

responsive

(SipeandBazzaz1994,Canhamet al. 1996,Lei

andLechowicz1997).As concludedby Walterset al. (1993

a,b), sugarmaple may be lessresponsiverelative to other

species

because

a greaterconcentration

of resources

maybe

allocatedto productionof protectivecompounds

to resist

herbivores

andpathogens.

However,ourstudyshowedthat

changein palisademesophylldimensionis high, an indicationof abilityto photosynthesize

in differinglightlevels.All

thesedata supportthe ecologicalobserVations

that sugar

maplehasa competitiveadvantage,

relativeto redandsilver

maple, in mesic shadyconditionswhere it can investin

resourceconservation

for survivalratherthanheightgrowth

increase(Pacalaet al. 1994, Kobe et al. 1995).

Findingsin ourstudyareconsistent

withthoseof Sipeand

Bazzaz(1994, 1995) who showedthat red maple survives

better,overall, acrosscanopyopeningsin a centralNew

Englandforestascompared

to sugarmaple.Thiswouldfit the

"generalist"growthof red maple.Our studyalsoprovides

evidencefor theability of red mapleto endureshadewithin

theforestunderstory

particularlyondriersites,asreportedin

studiesby Lorimer (1984) andKelty et al. (1988), andfor its

capacityto establishandgrowwell in thehighlight environmentspresentin earlyseralstageforest(OliverandStephens

to investigate

effectsof competitionunderfield situations.

In conclusion,

thisstudyis thefirstto provideinsightinto

someof the linkagesbetweenleaf structureandecological

site affinitiesfor maples.For example,in silver maple,a

speciesknownto be restrictedto hydricsites,the thinner

dimensions

in leaf structure(anaverageof t 7% lessthanred

maple,the specieswith the thickestdimensions),

and the

overalllowerlevelof leaf responsiveness

to changein light

(anaverageof 23% lessthanredmaple,themostresponsive

species),make it the most susceptible

to desiccation

as

comparedto the other two maple species.Sugar maple

exhibitedchangesin cuticleandpalisademesophyllthicknesscomparableto red maplesuggesting

an ability to adapt

to varyinglightlevels.Ecologicalstudieshavedemonstrated

sugarmapletobethemostshadetolerantandin keepingwith

thisit hadthetallestheight,andgreatestrootcollardiameter

androot biomassof the threespeciesin the low light treatment.Red maplehadthe largestleaf structuredimensions

acrossalmostall lighttreatments,

andalsogreatestallocation

to root biomassunderdeepshadeas comparedto the other

maples, supportingits known toleranceto varying light

conditions

(opento deepshade)andwater-limitingenvironments.This studyshowsthat determinationof anatomical

and morphologicalcharacteristics

correlatewell with the

observedecologicaldistributionof thesespecies.Determining whereecologicalperformances

do not agreewith leaf

structuralandfunctionalattributespermitsexplorationof the

effectsof competition

onlandscape

patternsof distribution

of

thesespecies.

1977, Hibbs 1983).

Literature

Sipe and Bazzaz (1995) reportedsugarmapleto be the

leastresponsive

todifferences

inmicroenvironment.

Ellsworth

andReich(1992) suggestsugarmapleto be water-useeffiCientandconservative

in growthallocation.Our studyis

consistentwith their findings,but also demonstrates

that

sugarmaplehasthe leastoverallresponsiveness

in wholeplantsize(22-63% lessin height,rootcollardiameteranddry

mass)to differentlight treatmentsof the maplesthat we

examined.However,anatomicalmeasures(palisademesophyllthickness,

cuticlethickness)

of sugarmaplein ourstudy

demonstratedthat, at the leaf level, it was responsiveto

differences

in light.Similarly,Canham(1985, 1988)showed

that,thoughsugarmapleis shadetolerantandcanestablish

in forestunderstoryconditions,it growsbestunderhigher

lightregimesof canopyedgesandopenings.Canham(1988)

categorizedsugarmaple as a small gap specialistusing

Denslow's(1980) terminology.

Therearelimitationsto usingshort-termgreenhouse

experiments(wherecompetitionhasbeenexcluded)for comparinggrowthof plantsin differinglight environments,

and

then usingtheseresultsto relateto their knownecological

affinitiesof siteandshade-tolerance

in thewild.Forexample,

whengrownunderfield conditions,shadeintolerantspecies

die in low light regimes,and shadetolerantspecieswill

survive,making measuresof plasticityand performance

differentfrom thosegrownin the greenhouse

(Pacalaet al.

1994, Kobeet al. 1995).Furtherstudiesarethereforeneeded

518

ForestSctence

45(4) 1999

Cited

ASh'TON,

P.M.S. 1992.Establishment

andearlygrowthof advanceregenerationof canopytreesin moistmixed-species

broadleafforest.P. 101-125

in Theecologyandsilvicultureof mixed-species

forests,KeltyM.J.,et al

(eds.).Kluwer AcademicPubl., Dordrecht,The Netherlands.

ASHTON,

P.M.S., ANDG.P. BERCYN.

1992.Leaf adaptations

of someShorea

speciesto sunandshade.New Phytol.121:587-596.

ASh'TON,

P.M.S,AN[•G.P.BEP,

LYN.1994.A comparison

ofleafphysiology

and

anatomyof Quercus(sectionErythrobalanus-Fagaceae)

speciesin differentlight environments.Am. J. Bot. 81:589-597.

ASHTON

P.M.S.,AN[•B.C. LARSON.

1996.Germination

andseedlinggrowthof

Quercus(sectionErythrobalanus)

acrossopenings

in a mixed-deciduous

forestof southernNew England,USA. For. Ecol. Manage80:81-94

BAzzaz,F.A. 1979.Thephysiological

ecologyof plantsuccession.

Ann.Rev

Ecol. Syst.10:351-371.

B•zz•z, F.A., ANDR.W. CARLSON.

1982. Photosynthetic

acclimafionto

variabilityin thelightenvironment

of earlyandlatesuccessional

plants

Oecol. 54:313-316.

BERLYN,

G.P., ANDJ.P. MW,SCHE.1976. Botanicalmicrotechnique

and cytochemistry.

IowaStateUniversityPress,Ames,Iowa. 326p.

BURNS,

R.M., AN[•B.H. HONV•CA

(eds.).1990.Silvicsof NorthAmerica:Vol

2, Hardwoods.USDA For. Serv.Agfic. Handb.No. 654, US Gov.Print

Off., Washington,DC.

CAN•AM,

C.D, 1985.Suppression

andreleaseduringcanopyrecruitment

•n

Acer saccharum. Bull. Tom Bot. Club 112:134-145.

CA•AM, C.D. 1988.Growthandcanopyarchitecture

of shade-tolerant

trees

response

to canopygaps.Ecol.69:786-795.

CANhAM,

C.D.,ETAL.1990.Lightresponses

beneath

closedcanopies

andtreefall gapsin temperate

andtropicalforests.Can.J. For.Res.20:620-631

CANHAM,

C.D., ET AL. 1996. Biomassallocationand multipleresource

limitationin treeseedlings.

Can.J.For.Res.26:1521-1530.

CARPENTER,

S.B., ANDN.D. SMrm. 1975. A comparativestudyof leaf

thickness

among

southern

Appalachian

hardwoods.

Can.J.Bot.59:13931396.

DELUCIA,

E.H.,, T.W. SIPE,J. HERRICK,

ANDH. MAI•RALI.1998. Sapling

biomass

allocation

andgrowthintheunderstory

ofa deciduous

hardwood

forest. Am. J. Bot. 85:955-963.

LEI,T.T, ANDM.J.LECHOWICZ.

1997.Thephotosynthetic

response

of eight

species

of Acerto simulated

lightregimesfromthecentreandedgesof

gaps.Funct.Ecol. 11:16-23.

LEI,T.T, ANDM.J.LECHOWlCZ.

1998.Diverseresponses

of maplesaplings

to

forestlightregimes.Ann.Bot.82:9-19.

LOACH,

K. 1967.Shade

tolerance

intreeseedlings.

I. Leafphotosynthesis

and

respiration

in plantsraisedunderartificialshade.

New Phytol.66:607621.

DENSLOW,

J.S. 1980.Gap partitioningamongtropicalrain foresttrees.

Biotropica

(Supplement)

12:47-55.

LOACH,

K. 1970.Shadetolerancein treeseedlings.

II. Growthanalysisof

plantsraisedunderartificialshade.New Phytol.69:273-286.

EGLER,

F.E.1954.Vegetation

science

concepts:

I Initialfloristiccomposition:

A factorin old-fieldvegetation

development.

Vegetatio4: 412-417.

LORIMER,

e.G. 1984.Development

oftheredmapleunderstorey

innortheast-

ELLSWORm,

D.S.,ANDP.B.REICH.

1992.Waterrelations

andgasexchange

of

Acersaccharum

seedlings

in contrasting

naturallightandwaterregimes.

TreePhysiol.10:1-20.

OLIVER,

C.D., ANDE.P. STEPI-BEN$.

1977.Reconstruction

of a mixed-species

forestin centralNew England.Ecology58:562-572.

GABRmL,

W.J. 1990.Acersaccharinurn

L., silvermaple.P.70-77 in Silvics

of North America,Vol. 2, Hardwoods,Bums, R.M., and B.H. Honkala

(eds.).USDA For. Serv.Agric.Handb.No. 654, US Gov. Print.Off.,

Washington,

DC.

Go•rsc•IALr,,

K.W. 1994.Shade,leaf growthand crowndevelopment

of

Quercusrubra, Quercusvelutina, Prunus serotina and Acer rubrum

seedlings.

TreePhys.735-749.

GODMAN,R.M, H.W. YAVO•Y, ANDC.H. TtJBBS.1990. Acer Saccharurn

Marsh,sugarMaple. P. 78-91 in Silvicsof North America,Vol. 2,

Hardwoods,Bums,R.M., and B.H. Honkala(eds.).USDA For. Serv.

Agric.Handb.No. 654, US Gov. Print.Off., Washington,

DC.

GRONI•GER,

J.W., J.W. SElLeR,J.A. PETERSON,

ANDR.E. KITH. 1996. Growth

andphotosynthetic

responses

of four Virginia Piedmonttree speciesto

shade.Tree Phys.16:773-778

GRUBB,

PJ. 1977.Themaintenance

of species-rich

communities:

theimportanceof theregeneration

niche.Biol. Rev. 52: 107-145.

H•RLOW,W.M., E.S. HARRAR,

J.W. HARDn•ANDF.W. WHrrE.1991. Textbook

of dendrology.

Ed. 7. McGraw-Hill,New York.

HiBBS,

D.E. 1983.Fortyyearsof forestsuccession

in centralNew England.

em oak forests. For. Sci. 30:3-22.

PACALA,

S.W.,C.D. CANHAM,

J.A.SILANDER,

ANDR.K. KOBE.

1994.Sapling

growthasa function

ofresources

in a northtemperate

forest.Can.J.For.

Res. 24:2172-2183.

REICH,P.B., M.G. TJOELKER,

M.B. WALTERS,

D.W. VANDERKLEIN,

ANDC.

BUSO•NA.1998.Closeassociation

of RGR, leaf androotmorphology,

seedmassandshadetolerancein seedlings

of nineborealtree species

grownin highandlow light.Funct.Ecol. 12:327-338.

SALISURY,

E.J. 1928.On the causes

andecologicalsignificance

of stomatal

frequencywith specialreferenceto woodlandflora. Philosoph.

Trans.

Roy.Soc.LondonB. 216:1-65.

SASINSTITUTE,

INC.1990.Statistical

AnalysisSystemusersguide:statistics.

Version5. SAS Institute,Car•, NC.

SIPE,

T.W.,AND

F.A.BAZZAZ.

1994.Gappartitioning

amongmaples

(Acer)in

centralNew England:Shootarchitecture

and photosynthesis.

Ecol.

75:2318-2332.

SIPE,

T.W., ANDF.A. BAZZAZ.

1995.Gappartitioning

amongmaples(Acer)in

centralNew England:Survivalandgrowth.Ecol.76:1587-1602.

WALTERS,

M.B., AnDP.B. REICH.1996. Are shadetolerance,survival,and

growthlinkedto low lightandnitrogeneffectson hardwoodseedlings.

Ecol. 77:841-853.

Ecol. 64: 1394-1401.

WALTERS,

M.B., E.L. KRUGER,

AND P.B. REiCH.1993a. Growth, biomass

Host,

mR,J.F. 1960. Relativetoleranceto completeinundationof fourteen

bottomland

treespecies.

For. Sci.6:246-251.

distribution

andCO2 exchange

of northernhardwoodseedlings

in high

andlowfight:Relationships

withsuccessional

status

andshade

tolerance.

Oecol. 94:7-16

JACKSON,

L.W.R. 1967a.Effect of shadeon leaf structureof deciduoustree

species.Ecol. 48:498-499.

JACr,

SON,L.W.R. 1967b. Relation of leaf structureto shade tolerance of

dicotyledonous

treespecies.

For.Sci. 13:321-323.

KELTY,M.J., E.M. GOULD,

A•D M.J. TW•R¾.1988.Effectsof understory

removalin hardwood

stands.

North.J.Appl.For.4:162-164.

KOBE,R.K., S.W. PACALA,

J.A. SmANDER,

ANDC.D. CANHAM.

1995.Juvenile

treesurvivorship

asa component

of shadetolerance.

Ecol.Appl.5:517532.

LF•, D.W. 1985.Duplicating

foliageshadefor research

on plantdevelopment. Hortscience 20:28-30.

LF• D.W., K. BAS•O•RAM,

M. MASSOR,H. MOm•AD,ANDS.K. YAP. 1996.

Irradianceand spectralqualityaffectAsiantropicalrain foresttree

seedling

development.

Ecol.77:568-580.

WALTERS,

M.B., E.L. KRUGER,

ANDP.B.REICH.1993b.Relativegrowthratein

relationto physiological

andmorphological

traitsfor northemhardwood

seedlings:

Species,light environment

and ontogenetic

considerations.

Oecol. 96:219-231.

WALTERS,

R.S., ANDH.W. YAWNEY.

1990.AcerrubrumL., redmaple.P. 6069 in Silvicsof NorthAmerica,Vol. 2, Hardwoods,Bums,R.M., andB.H.

Honkala(eds.).USDA For.Serv.Agric.Handb.No. 654, US Gov.Print.

Off., Washington,

De.

WESTVELD,

M., ETAL.1956.Naturalforestvegetation

zonesinNewEngland.

J. For. 54: 332-338.

WILL, R.E., J.R. SELLER,

P.P. FERET,ANDW.M. AIJST.1995. Effects of

rhizospere

inundation

onthegrowthandphysiology

of wetanddry-site

Acerrubrum(redmaple)populations.

Am. Midl. Natur.134:127-139.

LEi,T.T., AnDM.J.LECHOVaCZ.

1990.Shadeadaptation

andshadetolerance

in saplings

of threeAcerspeciesfromeasternNorthAmerica.Oecol.

(Berlin) 84:224-228.

ForestSctence

45(4)1999 519