PP RS An Assessment of Municipal Annexation in Georgia and

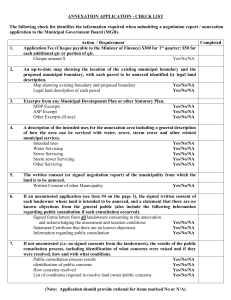

advertisement