Abstract

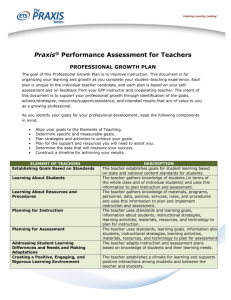

advertisement